Science Teacher: Roles, Skills, and Career Path

Science Teacher: Roles, Skills, and Career Path

Science Teacher: Roles, Skills, and Career Path

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

A science teacher designs and delivers standards-aligned instruction in biology, chemistry, physics, or earth science, manages laboratory safety protocols including chemical storage and equipment maintenance, assesses student learning through formative and summative methods, and maintains required documentation such as safety waivers and IEP accommodations. They typically teach 5-6 class periods daily, with 1-2 prep periods for lab preparation and grading.

Teaching science means juggling open flames, teenage emotions, and paperwork that could sink a battleship. You are part content expert, part safety officer, and part equipment technician. The job looks like lectures and labs from the hallway, but the real work happens in the margins of your day.

For a 9th-grade biology teacher, the day runs on precise intervals: five 45-minute periods of direct instruction covering cell structure or genetics, with 20 minutes before each lab to set up microscopes and prep agar plates. You will spend 90 minutes daily grading formative assessment exit tickets and lab reports, plus 30 minutes weekly on parent contact logs. That prep period disappears faster than dry ice in water.

A science teacher designs and delivers standards-aligned instruction in biology, chemistry, physics, or earth science, manages laboratory safety protocols including chemical storage and equipment maintenance, assesses student learning through formative and summative methods, and maintains required documentation such as safety waivers and IEP accommodations. They typically teach 5-6 class periods daily, with 1-2 prep periods for lab preparation and grading.

Teaching science means juggling open flames, teenage emotions, and paperwork that could sink a battleship. You are part content expert, part safety officer, and part equipment technician. The job looks like lectures and labs from the hallway, but the real work happens in the margins of your day.

For a 9th-grade biology teacher, the day runs on precise intervals: five 45-minute periods of direct instruction covering cell structure or genetics, with 20 minutes before each lab to set up microscopes and prep agar plates. You will spend 90 minutes daily grading formative assessment exit tickets and lab reports, plus 30 minutes weekly on parent contact logs. That prep period disappears faster than dry ice in water.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

What Does a Science Teacher Do?

AP Chemistry hits different. Same five class periods, but now you are managing 90-minute alternating block schedules where one day is lecture and the next is titration labs. The prep time doubles because you are calculating molarities and inspecting burettes for cracks. Grading takes longer too—those stoichiometry problems do not check themselves, and you are documenting scientific method mastery for the College Board audit.

Laboratory safety is not a poster on the wall. It is three non-negotiable protocols you check daily:

GHS-aligned chemical storage segregated by compatibility group, meaning your acids live far from your bases in locked cabinets with hazard diamonds facing out.

Annual OSHA-mandated eye wash station testing logs, running the water for 15 minutes weekly and documenting pressure readings in a binder the fire inspector will actually ask to see.

NFPA 45 ventilation requirements for prep rooms storing volatile substances like ether or concentrated hydrochloric acid.

One mistake with chemical compatibility and you are explaining to the principal why the hallway smells like sulfur.

The modern science teacher runs a specific tech stack. I use Vernier LabQuest 3 units for data collection—about $329 per device—to graph motion and temperature in real time during inquiry-based learning activities. Google Classroom manages the chaos of late assignments and missing permission slips. When physical supplies run out or a student is absent, Pivot Interactives fills gaps at $8 per student per year for virtual labs that still teach experimental design. You learn quickly which platforms sync with your gradebook and which ones demand double entry.

Elementary teachers approach teaching science as generalists, squeezing 45-minute science blocks into a schedule dominated by reading and math, usually three times weekly with broad certification covering all subjects. Secondary specialists live in deeper waters. You hold single-subject endorsements in biology or chemistry, manage 90-minute alternating block schedules, and develop the pedagogical content knowledge to explain electron configuration without dumbing it down. The Next Generation Science Standards guide both, but the prep looks completely different. A kindergarten teacher explaining weather patterns faces different challenges than an AP Physics teacher breaking down angular momentum.

Why Are Science Teachers Critical to STEM Education?

Science teachers serve as the primary gatekeepers to STEM careers by developing students' scientific literacy and inquiry skills during formative middle and high school years. Research indicates that effective science instruction significantly increases the likelihood of students pursuing STEM majors, addressing critical workforce shortages in fields like engineering and biotechnology while ensuring civic scientific literacy.

You can't fix the STEM pipeline with better college counseling. By then, the damage is done. Middle schoolers decide whether they're "science people" long before they fill out applications, and a science teacher with strong pedagogical content knowledge makes that difference.

John Hattie's Visible Learning meta-analysis puts teacher expertise at an effect size of 0.63 on student achievement. That's substantial. But here's what matters for our field: science-specific pedagogical content knowledge beats general teaching experience when it comes to conceptual change. A veteran English teacher shifted to biology won't move the needle like someone who understands common misconceptions about photosynthesis. Your inquiry-based learning strategies only work if you know exactly where students trip over the scientific method.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 168,000 annual STEM job openings through 2032. Meanwhile, ACT data shows only 20% of high school graduates hit STEM readiness benchmarks. We call this the "leaky pipeline," but that's generous. It's more like a gushing hole, and integrative STEM education depends on fixing it at the K-12 level, not the university level.

Stop tailoring lessons to Visual, Auditory, or Kinesthetic "styles." Hattie's research shows that approach yields an effect size of 0.03—essentially zero. Yet 90% of teachers still believe the myth. Instead, match the modality to the content. Use animations when teaching molecular motion. Get kids physically pushing against walls when demonstrating physics forces. Match the tool to the concept, not the kid's supposed learning style.

Here's the number that should wake up administrators. Students with just one highly effective science teacher in grades 6-8 are significantly more likely to declare STEM majors in college. The lifetime earnings differential between STEM and non-STEM careers exceeds $1.2 million. One teacher. Three years. Over a million dollars in economic impact per student. That's not philanthropy; that's infrastructure.

The Next Generation Science Standards aren't just new benchmarks; they're a bet that better science learning requires three-dimensional instruction. That means integrating disciplinary core ideas, crosscutting concepts, and science practices. You can't fake this with worksheets. It demands formative assessment that catches misconceptions in real time, not after the unit test.

Laboratory safety isn't separate from instruction—it's part of it. When students handle burners and chemicals responsibly, they're practicing the same executive function skills they'll need in research labs. Your formative assessment of their technique matters as much as their hypothesis. I watch my 8th graders measure precisely, and I see future technicians, nurses, and engineers.

I saw this play out last year with a student named Marcus. He entered 7th grade convinced he was "bad at science" because he failed a memorization-heavy unit in elementary school. We focused on inquiry-based learning—asking questions about local water quality, not defining vocabulary words. By October, he was designing his own controlled experiments. By June, he wanted to be a civil engineer. That's the gatekeeping role in action.

The shift to Next Generation Science Standards reveals who has deep pedagogical content knowledge and who's winging it. Teachers with content expertise know that formative assessment during a lab reveals more than final grades ever could. They notice when a student measures volume incorrectly and correct the technique immediately. That moment of feedback matters more than another PowerPoint slide.

That $1.2 million figure isn't abstract economics in my classroom. It's Marcus buying a house someday. It's his sister affording medical school. When we talk about the "leaky pipeline," we're talking about real kids losing real money because someone convinced them they couldn't handle science learning at age thirteen. Your classroom is wealth creation.

Laboratory safety drills aren't time wasters. When I spend September teaching proper goggles use and chemical handling, I'm building the procedural fluency that allows complex investigations later. You can't do inquiry-based learning if students might set the room on fire. Safety protocols enable the risk-taking that real science requires.

The Day-to-Day Reality: Curriculum, Labs, and Assessment

Being a science teacher means you spend Sunday afternoons counting gel electrophoresis trays, not just inspiring future astronauts. You arrive early to check the fume hoods and leave late because Sammy's beaker cracked and you need to file an incident report. The gap between the Instagram version of teaching and the 6:45 AM chemical inventory check is where your pedagogical content knowledge gets tested. You need systems that survive contact with reality.

Lab type determines your week. I track prep time religiously because 3rd period waits for no one. Here is how the options compare.

Lab Type | Prep Time | Cleanup | Inquiry Level | Safety Incidents/Year* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cookbook Labs | 30 minutes | 15 minutes | Low | 0.8 |

Inquiry Labs | 90 minutes | 30 minutes | High | 2.4 |

Microscale Chemistry | 15 minutes | 5 minutes | Moderate | 0.2 |

*Per 1000 student-lab hours based on district laboratory safety logs.

Cookbook Labs feel safe. Students follow steps. You know exactly when the solution turns blue. But boredom is a safety hazard too. Kids start playing with the faucets.

Inquiry-based learning eats your prep periods. Last Tuesday, I spent 86 minutes setting up six different stations for a cellular respiration investigation. Students designed their own variables. Two groups melted pip tips on the hot plate. The learning science tells us open inquiry boosts retention, but the trade-off is real: you'll reset those stations while eating lunch at your desk. The data is worth it. Watching a kid realize why yeast respires faster with sugar never gets old. That moment justifies the cleanup.

Microscale Chemistry saved my sanity during hybrid scheduling. You use drop-scale reactions in well plates. Prep drops from thirty minutes to fifteen. Cleanup shrinks to five minutes. Waste disposal becomes trivial. The incident rate plummets because students handle microliters, not beakers. I can run twelve simultaneous reactions on one sheet of paper. Each well uses three drops of indicator instead of thirty milliliters. The cost savings on reagents alone funded my new projector.

Assessment runs on a three-tier cycle. Weekly Claim-Evidence-Reasoning (CER) write-ups consume twenty minutes per student. That's six hours for a standard load of 180 kids. I grade these during basketball games on Tuesday nights. The formative assessment value is immediate. You spot misconceptions about controlled variables before they fossilize. I use a simple rubric: claim clear? evidence relevant? reasoning connects? You learn to scan for the word "because"—if it's missing, the reasoning is hollow.

Monthly Next Generation Science Standards-aligned performance tasks—like the Carbon Cycle Model—require 3D assessment rubrics scoring scientific method practices alongside content. You evaluate crosscutting concepts, not just vocabulary. Last month, I watched a student model carbon sequestration using only aquarium gravel and charcoal. The rubric tracked systems thinking, not memorization.

Semester lab practicals rotate students through eight stations at eight-minute intervals. You proctor, reset, and pray no one knocks over the iodine. I once had a kid faint at the dissection station. We called the nurse, sanitized the frog, and kept rotating. The bell schedule doesn't negotiate.

When Labs Go Wrong:

Contaminated bacterial cultures: Autoclave everything immediately. Do not open plates. Pivot to digital microscopy of prepared slides. Students still practice sterile technique reasoning without the staph risk.

Broken Vernier probes: Switch to manual measurement. Teach uncertainty propagation using rulers and stopwatches. The formative assessment value actually increases—students see error margins in real time.

Chemical shortages: Substitute 0.1M HCl with household vinegar. Calculate the molarity adjustment (acetic acid runs 0.83M). Students do stoichiometry to scale volumes. Crisis becomes curriculum.

Paperwork buries you. Fifteen percent of your roster carries IEPs requiring modified lab protocols—perhaps no open flames or alternate data collection methods. I keep a laminated checklist for each student taped to my clipboard. 504 plans mandate specific fume hood seating for respiratory issues. You track these on your seating chart with color codes. Red circles mean front row only. Blue triangles mean no ethidium bromide exposure.

Then there's the annual safety waiver circus: 150+ signatures per semester, tracked in three places because one parent always claims they "never got it." I use digital signatures now, but I still print backups. The autoclave log alone takes twenty minutes weekly. The fire marshal inspects your eyewash stations quarterly. You document every incident, even when Jake "just tripped" near the Bunsen burner. The paperwork protects you, the school, and ultimately the students.

You survive by borrowing templates from STEM teacher resources and curriculum platforms. I built a database to streamline your curriculum development framework—tracking which labs work with specific accommodations, which probes break every October, and exactly how much vinegar equals that missing hydrochloric acid. Last week, this system saved me forty minutes when the district delivery failed. I knew exactly which microscale protocol to pull.

Required Credentials and Subject Matter Expertise

Becoming a science teacher requires checking specific boxes before you ever write a lesson plan. State boards want proof you know your content and can manage laboratory safety. Without these credentials, you cannot legally supervise students using Bunsen burners or chemical reagents.

Check your transcripts early. That biology class from community college might not count toward the 8-hour lab requirement if it was lecture-only.

Here is the traditional certification checklist most states follow:

Bachelor's degree from a regionally accredited university. Most programs require a 3.0 GPA minimum to enter student teaching. Some competitive programs demand 3.5 for secondary science placements. A 2.9 usually disqualifies you, no exceptions.

Content-specific semester hours: Complete 24-36 hours in your endorsement area.

edTPA portfolio: Submit video clips and lesson analyses scoring 42+ out of 90. This performance assessment measures your pedagogical content knowledge in real classroom settings. You film yourself guiding students through inquiry-based learning.

Praxis Subject Assessment: Pass your specific exam. The General Science: Content Knowledge (5435) requires a 154 out of 200 minimum. Chemistry and physics exams demand higher cut scores and include calculator-active sections.

Student teaching placement typically happens in your final semester. You will teach five periods daily while completing edTPA documentation. Start filming by October to avoid December crunch time.

Content knowledge separates science teachers from generalists. You need to explain why mitosis differs from meiosis without checking Google. Students smell uncertainty.

Your background determines the fastest route to the classroom.

Which Pathway Is Right For You?

Map your decision based on current degrees and cash flow:

Traditional: Four-year university program costing $40k-80k. Best if you are entering college or switching careers with time to spare. You graduate with full certification and 16 weeks of student teaching experience.

Alternative: Programs like ABCTE or Teach For America run 6 months and cost $5k-15k.

Emergency Provisional: Pass your content exam and get hired immediately. You have a 2-year window to complete pedagogy coursework while teaching full-time. Your district assigns a mentor who reviews your laboratory safety protocols weekly.

Emergency provisional hires often struggle most with classroom management. You learn formative assessment techniques while simultaneously managing 30 freshmen with scalpels.

The hard truths about those exams matter for your timeline. Praxis Biology Content Knowledge (5235) first-time pass rates hover between 65-75% nationally. Many candidates fail the cellular processes and genetics sections specifically.

I spent 6-8 weeks preparing using ETS practice tests ($19.95) and spaced-repetition flashcards. Plan for 90 minutes of study daily. If you fail, you wait 28 days and pay another $150 to retake. Three attempts max per year.

Beyond the ETS materials, Quizlet decks organized by Praxis code help. I drilled the 5235 deck during my commute. The $19.95 investment beats the $150 retake fee.

Reciprocity sounds simple but carries fine print that delays hiring. While 45 states participate in NASDTEC interstate agreements, transfers are not automatic. You still submit transcripts, pay fees, and wait.

California requires additional CTEL coursework (45 hours) if you land in ESL-heavy districts like LAUSD. Texas mandates the PPR exam (160+ score) regardless of your out-of-state experience. New York forces veteran teachers to submit edTPA portfolios even with ten years of inquiry-based learning units under their belts.

Florida skips the edTPA but demands a specific classroom management course. Research your target state's unique addons before you box up the lab equipment.

Consider the benefits of a Master's degree for career advancement before you start. Some states pay for it through grow-your-own programs. Districts offer tuition reimbursement ranging from $2k-5k annually.

Others require graduate credits within five years of hire to maintain your license. Advanced coursework deepens your understanding of Next Generation Science Standards and the scientific method itself. You learn to write better formative assessments.

Teaching science means proving you can guide students through the scientific method while keeping them safe. Your credential is the legal permission to do both. Start gathering transcripts now. The bureaucratic wheel turns slowly, and the application fee alone runs $200 in most states.

Proven Instructional Strategies for Engaging Science Learners

You can't teach photosynthesis with lectures alone. I learned that the hard way during my first year. A good science teacher needs multiple strategies because cellular respiration and atomic structure require different approaches.

John Hattie's research gives us hard numbers. Direct Instruction shows an effect size of d=0.59. Unguided Open Inquiry sits at d=0.30. That gap matters when you're planning Monday's lesson.

Direct Instruction: Thirty-minute prep, high structure, immediate feedback, low safety risk. The d=0.59 effect size makes it efficient for new content.

Open Inquiry: Ninety-minute prep, high autonomy, delayed guidance, elevated safety concerns. The d=0.30 drops further without proper scaffolding.

The safety risk jumps with inquiry. Novices burn themselves or misuse chemicals while you're troubleshooting group dynamics across the room. I once had a student add acid to water incorrectly during an open inquiry because I was helping another group across the lab.

The 5E Instructional Model balances both worlds. I used it last October with 7th graders studying cellular respiration. The sequence took seventy minutes total, broken into five chunks.

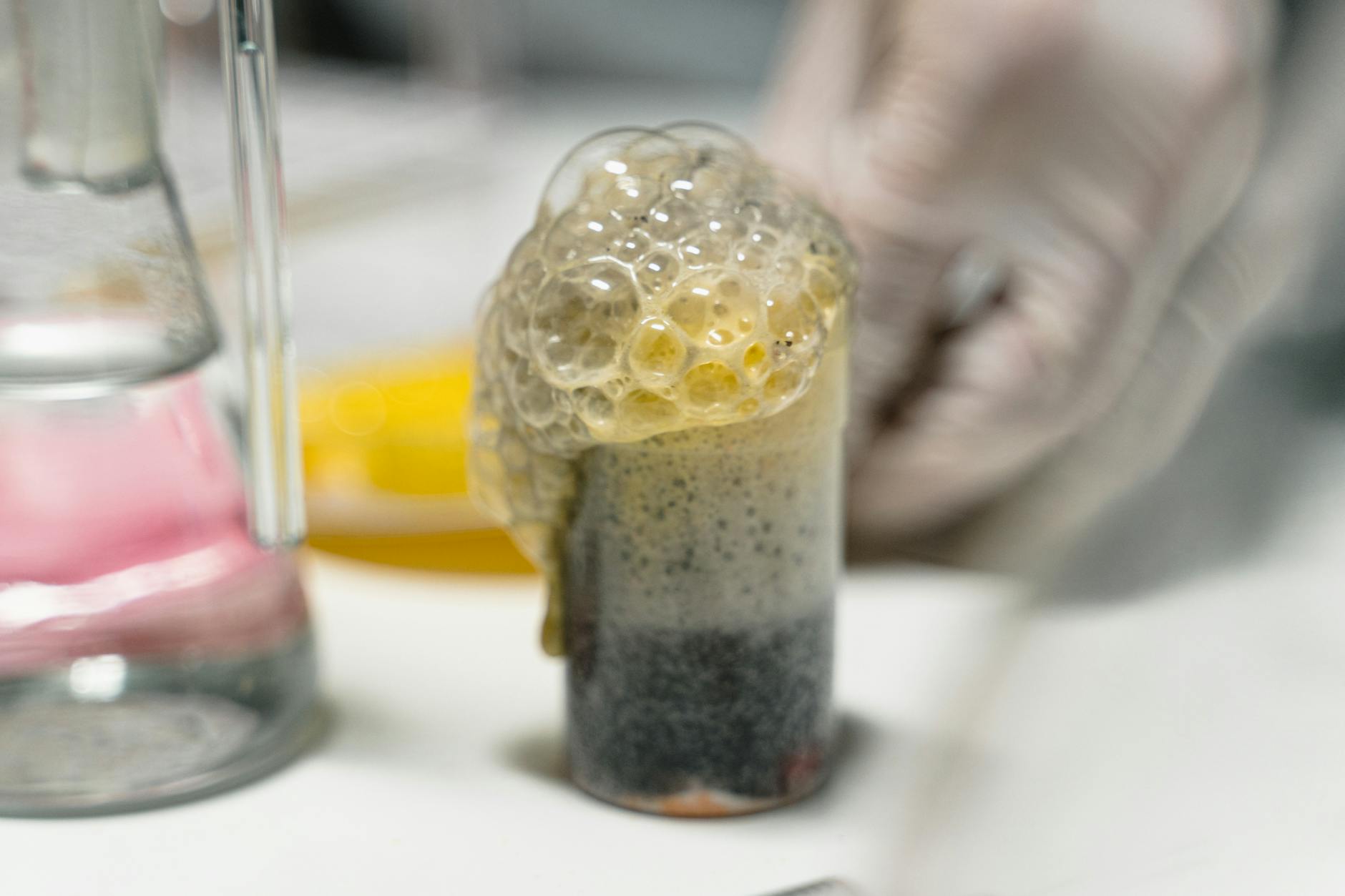

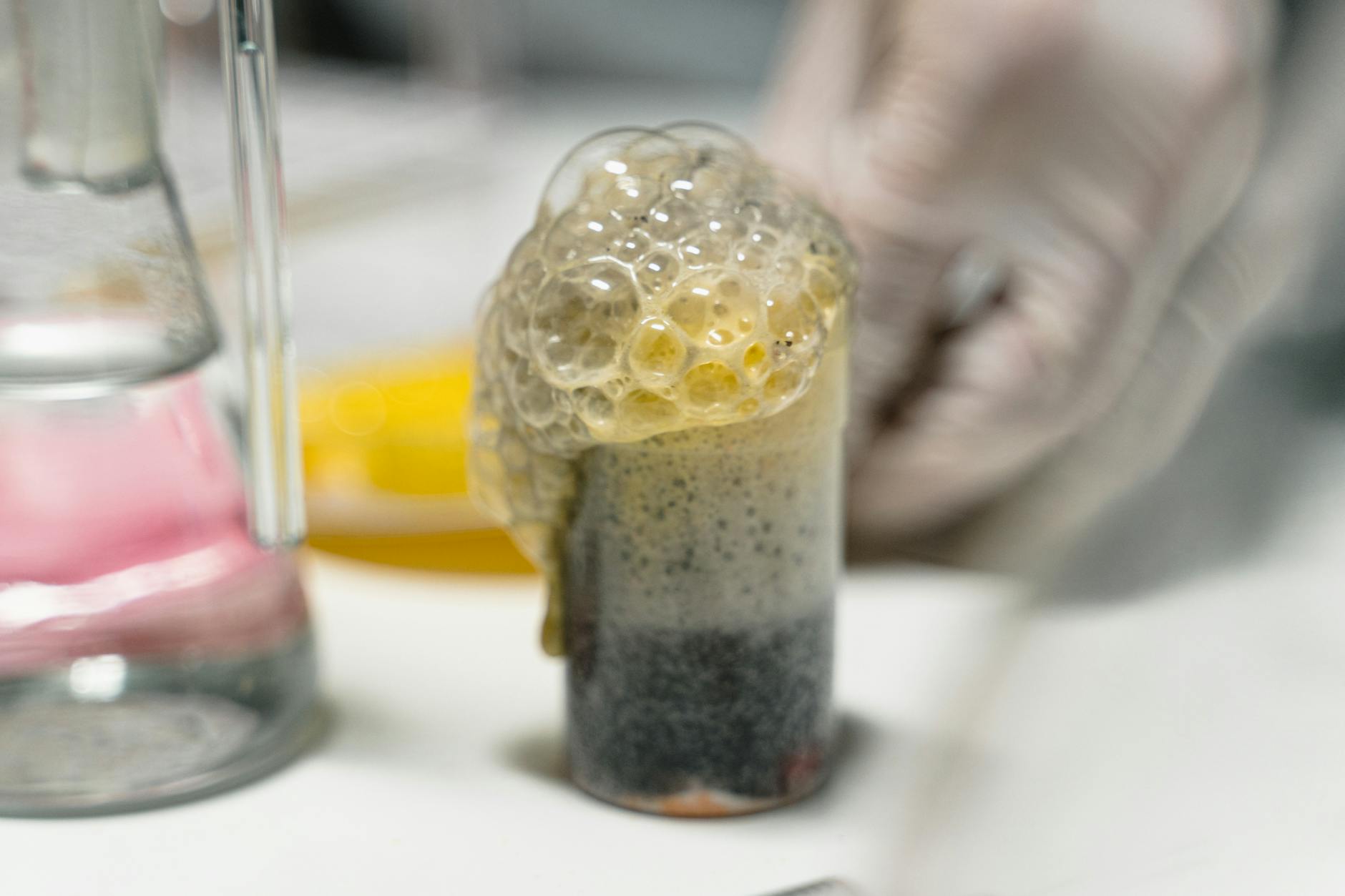

Engage started with a yeast balloon demo. Ten minutes of watching bread rise beats any textbook opener. Explore used bromothymol blue pH indicators with elodea in test tubes. That hands-on learning in the classroom showed CO2 production better than my diagrams ever could as kids watched the color shift from blue to yellow.

Explain followed with fifteen minutes of lecture connecting the demo to ATP equations. Elaborate had students compare photosynthesis and respiration equations side-by-side for another fifteen minutes.

Evaluate meant a CER exit ticket. Students claimed the yeast produced gas, cited the balloon data, and explained the cellular respiration equation. Ten minutes of formative assessment told me who needed reteaching.

For high school chemistry, I use POGIL—Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning. It works for Next Generation Science Standards alignment without the chaos of pure discovery. The structured activities build science learning through data analysis, replacing traditional lecture.

Students sit in fixed groups of four with assigned roles. The Manager keeps time, the Presenter speaks for the group, the Recorder writes, and the Reflector checks understanding. They work through Periodic Trends activities over two class periods—ninety minutes total.

Your job is asking "why" when they present answers, not giving solutions. I circulate with a clipboard, listening for pedagogical content knowledge gaps. If the Manager lets one student dominate, I pause the group. When the Recorder writes incomplete equations, I point to the data table.

Here's the hard truth. Direct instruction outperforms inquiry-based learning for students below the fiftieth percentile in reading comprehension. If they can't decode the lab instructions, they learn nothing from the activity.

Same with laboratory safety. Kids without prior technique training need explicit modeling first. They don't instinctively know how to use a pipette or read a meniscus. Save open inquiry for honors or AP classes with established safety protocol mastery and self-regulation skills.

When the scientific method feels stale, I supplement with educational games for STEM classrooms. But games don't replace the heavy lifting of learning science through structured inquiry.

Match the strategy to your learners' readiness. That's the difference between real science learning and just doing busywork.

How Do You Become a Science Teacher?

To become a science teacher, earn a bachelor's degree in science or education, complete a state-approved teacher preparation program with student teaching, pass required Praxis exams (Core and Subject Assessment), and apply for state licensure. Alternative certification routes exist for career changers with science degrees, typically requiring 5-8 weeks of intensive training and a provisional license.

Content credentials come first. You need either 60 semester hours of science courses or a Bachelor's in Secondary Science Education. Most universities require a 3.0 GPA to place you in student teaching. I started with the 4-year route, which builds your pedagogical content knowledge for teaching science effectively.

The 2-year pathway suits career changers who already hold a biology or chemistry degree. You transcript 60 science credits and add education courses focused on teaching science. The 4-year Bachelor's in Secondary Science Education mixes content with methods courses. Both paths require maintaining that 3.0 GPA through your junior year to qualify for placement.

Your coursework includes physics, chemistry, biology, and earth science regardless of which path you choose. You will dissect specimens, balance chemical equations, and study geology. Universities check that you have breadth across disciplines, not just depth in one area. This ensures you can teach middle school integrated science or high school biology with equal confidence.

Next, pass the required examinations. The Praxis Core Academic Skills tests require these minimum scores:

Reading: 156

Writing: 162

Math: 150

Then take your Praxis Subject Assessment—Biology: Content Knowledge (5235) requires a 154, or take General Science (5435). Budget $150-210 per exam plus $50-75 for study guides.

Schedule your Praxis exams during your junior year or early senior year. The Core tests your basic skills; the Subject Assessment digs into inquiry-based learning theory and content knowledge. Buy the official study guides. I failed the first writing attempt by two points and had to reschedule—budget time for retakes.

Some states accept alternative exams like NES or state-specific tests instead of Praxis. Check your Department of Education website before buying study materials. Register early—testing centers fill up in October when seniors book their slots. Bring a government ID and leave your phone in the car; they are strict about security.

Complete your state-approved teacher preparation program. This includes:

150 clock hours observing in classrooms

450 clock hours of supervised student teaching

3-hour Recognizing and Reporting Child Abuse certification

Both a university coordinator and your mentor teacher evaluate your instruction. You cannot graduate without completing all 600 hours.

Those 450 hours of student teaching mean you are the teacher. You write the lesson plans, grade the labs, and handle the classroom management while your mentor observes. My university coordinator visited four times to evaluate my use of the scientific method in lessons. You also complete that mandatory child safety training online before stepping into any classroom.

During my student teaching, I learned to prep solutions the night before and always have a non-lab backup lesson ready. The 150 observation hours come first—you watch your mentor teach units on genetics and cell division. Take notes on how they transition from lecture to lab activity smoothly without chaos.

Apply for state licensure ($75-200) and submit fingerprints ($50-75). Most states then require a 1-2 year induction program. Mine involved monthly observations with a mentor who helped me navigate laboratory safety protocols and formative assessment strategies during my first year.

Induction programs pair you with a veteran science teacher from your building. You meet weekly, and they observe your instruction monthly. You document your growth in areas like laboratory safety procedures and formative assessment techniques. Some states call this "initial licensure" or "Level 1" status until you finish the two years.

Keep all your receipts for licensure fees; some districts reimburse these during your first year. The background check takes two to eight weeks depending on your state. You cannot step into a classroom without cleared fingerprints. Start this process in April before graduation to avoid delays in your August start date.

Career changers can skip the traditional path. Programs like Teach For America or TNTP run 5-week summer institutes with 50 hours of practice teaching. You get a provisional license, teach full-time immediately, and must finish a master's degree within two years.

The alternative route is not easier. You attend the 5-week institute from 8 AM to 6 PM daily, teaching summer school students for those 50 hours. Then you start August with your own classroom and full course load. You have two years to complete a master's degree while teaching, which means taking night classes or online courses during the school year.

Many career changers choose this route during economic downturns or mid-career pivots. You earn a salary immediately while learning on the job. However, you must balance lesson planning with graduate coursework, which means late nights and weekends. Support systems matter—find other alternative-route teachers in your cohort to survive the first semester.

Whether you choose the traditional or alternative route, prioritize understanding the Next Generation Science Standards and inquiry-based learning frameworks. Your modern teacher preparation should include classroom management for labs, not just theory. The first year is tough, but the credential opens doors to a career where you actually get to do experiments with kids every day.

Science Teacher: The 3-Step Kickoff

Teaching science means managing controlled chaos. You’ll juggle chemical inventories, hunt for missing goggles, and calm teenagers who think fire constitutes an experiment. But when a student connects photosynthesis to their wilting houseplant, that noise fades. You’re not just checking off Next Generation Science Standards; you’re building skeptics who trust evidence over clicks. Focus on pedagogical content knowledge—knowing why students confuse velocity with acceleration—not just facts.

Start exactly where you are. If you’re already in the classroom, pilot one inquiry-based learning protocol next month. If you’re earning credentials, shadow a teacher during lab setup week. Your first year feels like survival mode. Lock down laboratory safety routines until they’re automatic, then layer in the creative labs. Students remember the teacher who kept them safe and asked hard questions.

Audit your lab safety procedures against state guidelines this weekend.

Draft one inquiry-based unit using only materials already in your supply closet.

Email a veteran science teacher to request an observation during their messiest lab day.

What Does a Science Teacher Do?

AP Chemistry hits different. Same five class periods, but now you are managing 90-minute alternating block schedules where one day is lecture and the next is titration labs. The prep time doubles because you are calculating molarities and inspecting burettes for cracks. Grading takes longer too—those stoichiometry problems do not check themselves, and you are documenting scientific method mastery for the College Board audit.

Laboratory safety is not a poster on the wall. It is three non-negotiable protocols you check daily:

GHS-aligned chemical storage segregated by compatibility group, meaning your acids live far from your bases in locked cabinets with hazard diamonds facing out.

Annual OSHA-mandated eye wash station testing logs, running the water for 15 minutes weekly and documenting pressure readings in a binder the fire inspector will actually ask to see.

NFPA 45 ventilation requirements for prep rooms storing volatile substances like ether or concentrated hydrochloric acid.

One mistake with chemical compatibility and you are explaining to the principal why the hallway smells like sulfur.

The modern science teacher runs a specific tech stack. I use Vernier LabQuest 3 units for data collection—about $329 per device—to graph motion and temperature in real time during inquiry-based learning activities. Google Classroom manages the chaos of late assignments and missing permission slips. When physical supplies run out or a student is absent, Pivot Interactives fills gaps at $8 per student per year for virtual labs that still teach experimental design. You learn quickly which platforms sync with your gradebook and which ones demand double entry.

Elementary teachers approach teaching science as generalists, squeezing 45-minute science blocks into a schedule dominated by reading and math, usually three times weekly with broad certification covering all subjects. Secondary specialists live in deeper waters. You hold single-subject endorsements in biology or chemistry, manage 90-minute alternating block schedules, and develop the pedagogical content knowledge to explain electron configuration without dumbing it down. The Next Generation Science Standards guide both, but the prep looks completely different. A kindergarten teacher explaining weather patterns faces different challenges than an AP Physics teacher breaking down angular momentum.

Why Are Science Teachers Critical to STEM Education?

Science teachers serve as the primary gatekeepers to STEM careers by developing students' scientific literacy and inquiry skills during formative middle and high school years. Research indicates that effective science instruction significantly increases the likelihood of students pursuing STEM majors, addressing critical workforce shortages in fields like engineering and biotechnology while ensuring civic scientific literacy.

You can't fix the STEM pipeline with better college counseling. By then, the damage is done. Middle schoolers decide whether they're "science people" long before they fill out applications, and a science teacher with strong pedagogical content knowledge makes that difference.

John Hattie's Visible Learning meta-analysis puts teacher expertise at an effect size of 0.63 on student achievement. That's substantial. But here's what matters for our field: science-specific pedagogical content knowledge beats general teaching experience when it comes to conceptual change. A veteran English teacher shifted to biology won't move the needle like someone who understands common misconceptions about photosynthesis. Your inquiry-based learning strategies only work if you know exactly where students trip over the scientific method.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 168,000 annual STEM job openings through 2032. Meanwhile, ACT data shows only 20% of high school graduates hit STEM readiness benchmarks. We call this the "leaky pipeline," but that's generous. It's more like a gushing hole, and integrative STEM education depends on fixing it at the K-12 level, not the university level.

Stop tailoring lessons to Visual, Auditory, or Kinesthetic "styles." Hattie's research shows that approach yields an effect size of 0.03—essentially zero. Yet 90% of teachers still believe the myth. Instead, match the modality to the content. Use animations when teaching molecular motion. Get kids physically pushing against walls when demonstrating physics forces. Match the tool to the concept, not the kid's supposed learning style.

Here's the number that should wake up administrators. Students with just one highly effective science teacher in grades 6-8 are significantly more likely to declare STEM majors in college. The lifetime earnings differential between STEM and non-STEM careers exceeds $1.2 million. One teacher. Three years. Over a million dollars in economic impact per student. That's not philanthropy; that's infrastructure.

The Next Generation Science Standards aren't just new benchmarks; they're a bet that better science learning requires three-dimensional instruction. That means integrating disciplinary core ideas, crosscutting concepts, and science practices. You can't fake this with worksheets. It demands formative assessment that catches misconceptions in real time, not after the unit test.

Laboratory safety isn't separate from instruction—it's part of it. When students handle burners and chemicals responsibly, they're practicing the same executive function skills they'll need in research labs. Your formative assessment of their technique matters as much as their hypothesis. I watch my 8th graders measure precisely, and I see future technicians, nurses, and engineers.

I saw this play out last year with a student named Marcus. He entered 7th grade convinced he was "bad at science" because he failed a memorization-heavy unit in elementary school. We focused on inquiry-based learning—asking questions about local water quality, not defining vocabulary words. By October, he was designing his own controlled experiments. By June, he wanted to be a civil engineer. That's the gatekeeping role in action.

The shift to Next Generation Science Standards reveals who has deep pedagogical content knowledge and who's winging it. Teachers with content expertise know that formative assessment during a lab reveals more than final grades ever could. They notice when a student measures volume incorrectly and correct the technique immediately. That moment of feedback matters more than another PowerPoint slide.

That $1.2 million figure isn't abstract economics in my classroom. It's Marcus buying a house someday. It's his sister affording medical school. When we talk about the "leaky pipeline," we're talking about real kids losing real money because someone convinced them they couldn't handle science learning at age thirteen. Your classroom is wealth creation.

Laboratory safety drills aren't time wasters. When I spend September teaching proper goggles use and chemical handling, I'm building the procedural fluency that allows complex investigations later. You can't do inquiry-based learning if students might set the room on fire. Safety protocols enable the risk-taking that real science requires.

The Day-to-Day Reality: Curriculum, Labs, and Assessment

Being a science teacher means you spend Sunday afternoons counting gel electrophoresis trays, not just inspiring future astronauts. You arrive early to check the fume hoods and leave late because Sammy's beaker cracked and you need to file an incident report. The gap between the Instagram version of teaching and the 6:45 AM chemical inventory check is where your pedagogical content knowledge gets tested. You need systems that survive contact with reality.

Lab type determines your week. I track prep time religiously because 3rd period waits for no one. Here is how the options compare.

Lab Type | Prep Time | Cleanup | Inquiry Level | Safety Incidents/Year* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cookbook Labs | 30 minutes | 15 minutes | Low | 0.8 |

Inquiry Labs | 90 minutes | 30 minutes | High | 2.4 |

Microscale Chemistry | 15 minutes | 5 minutes | Moderate | 0.2 |

*Per 1000 student-lab hours based on district laboratory safety logs.

Cookbook Labs feel safe. Students follow steps. You know exactly when the solution turns blue. But boredom is a safety hazard too. Kids start playing with the faucets.

Inquiry-based learning eats your prep periods. Last Tuesday, I spent 86 minutes setting up six different stations for a cellular respiration investigation. Students designed their own variables. Two groups melted pip tips on the hot plate. The learning science tells us open inquiry boosts retention, but the trade-off is real: you'll reset those stations while eating lunch at your desk. The data is worth it. Watching a kid realize why yeast respires faster with sugar never gets old. That moment justifies the cleanup.

Microscale Chemistry saved my sanity during hybrid scheduling. You use drop-scale reactions in well plates. Prep drops from thirty minutes to fifteen. Cleanup shrinks to five minutes. Waste disposal becomes trivial. The incident rate plummets because students handle microliters, not beakers. I can run twelve simultaneous reactions on one sheet of paper. Each well uses three drops of indicator instead of thirty milliliters. The cost savings on reagents alone funded my new projector.

Assessment runs on a three-tier cycle. Weekly Claim-Evidence-Reasoning (CER) write-ups consume twenty minutes per student. That's six hours for a standard load of 180 kids. I grade these during basketball games on Tuesday nights. The formative assessment value is immediate. You spot misconceptions about controlled variables before they fossilize. I use a simple rubric: claim clear? evidence relevant? reasoning connects? You learn to scan for the word "because"—if it's missing, the reasoning is hollow.

Monthly Next Generation Science Standards-aligned performance tasks—like the Carbon Cycle Model—require 3D assessment rubrics scoring scientific method practices alongside content. You evaluate crosscutting concepts, not just vocabulary. Last month, I watched a student model carbon sequestration using only aquarium gravel and charcoal. The rubric tracked systems thinking, not memorization.

Semester lab practicals rotate students through eight stations at eight-minute intervals. You proctor, reset, and pray no one knocks over the iodine. I once had a kid faint at the dissection station. We called the nurse, sanitized the frog, and kept rotating. The bell schedule doesn't negotiate.

When Labs Go Wrong:

Contaminated bacterial cultures: Autoclave everything immediately. Do not open plates. Pivot to digital microscopy of prepared slides. Students still practice sterile technique reasoning without the staph risk.

Broken Vernier probes: Switch to manual measurement. Teach uncertainty propagation using rulers and stopwatches. The formative assessment value actually increases—students see error margins in real time.

Chemical shortages: Substitute 0.1M HCl with household vinegar. Calculate the molarity adjustment (acetic acid runs 0.83M). Students do stoichiometry to scale volumes. Crisis becomes curriculum.

Paperwork buries you. Fifteen percent of your roster carries IEPs requiring modified lab protocols—perhaps no open flames or alternate data collection methods. I keep a laminated checklist for each student taped to my clipboard. 504 plans mandate specific fume hood seating for respiratory issues. You track these on your seating chart with color codes. Red circles mean front row only. Blue triangles mean no ethidium bromide exposure.

Then there's the annual safety waiver circus: 150+ signatures per semester, tracked in three places because one parent always claims they "never got it." I use digital signatures now, but I still print backups. The autoclave log alone takes twenty minutes weekly. The fire marshal inspects your eyewash stations quarterly. You document every incident, even when Jake "just tripped" near the Bunsen burner. The paperwork protects you, the school, and ultimately the students.

You survive by borrowing templates from STEM teacher resources and curriculum platforms. I built a database to streamline your curriculum development framework—tracking which labs work with specific accommodations, which probes break every October, and exactly how much vinegar equals that missing hydrochloric acid. Last week, this system saved me forty minutes when the district delivery failed. I knew exactly which microscale protocol to pull.

Required Credentials and Subject Matter Expertise

Becoming a science teacher requires checking specific boxes before you ever write a lesson plan. State boards want proof you know your content and can manage laboratory safety. Without these credentials, you cannot legally supervise students using Bunsen burners or chemical reagents.

Check your transcripts early. That biology class from community college might not count toward the 8-hour lab requirement if it was lecture-only.

Here is the traditional certification checklist most states follow:

Bachelor's degree from a regionally accredited university. Most programs require a 3.0 GPA minimum to enter student teaching. Some competitive programs demand 3.5 for secondary science placements. A 2.9 usually disqualifies you, no exceptions.

Content-specific semester hours: Complete 24-36 hours in your endorsement area.

edTPA portfolio: Submit video clips and lesson analyses scoring 42+ out of 90. This performance assessment measures your pedagogical content knowledge in real classroom settings. You film yourself guiding students through inquiry-based learning.

Praxis Subject Assessment: Pass your specific exam. The General Science: Content Knowledge (5435) requires a 154 out of 200 minimum. Chemistry and physics exams demand higher cut scores and include calculator-active sections.

Student teaching placement typically happens in your final semester. You will teach five periods daily while completing edTPA documentation. Start filming by October to avoid December crunch time.

Content knowledge separates science teachers from generalists. You need to explain why mitosis differs from meiosis without checking Google. Students smell uncertainty.

Your background determines the fastest route to the classroom.

Which Pathway Is Right For You?

Map your decision based on current degrees and cash flow:

Traditional: Four-year university program costing $40k-80k. Best if you are entering college or switching careers with time to spare. You graduate with full certification and 16 weeks of student teaching experience.

Alternative: Programs like ABCTE or Teach For America run 6 months and cost $5k-15k.

Emergency Provisional: Pass your content exam and get hired immediately. You have a 2-year window to complete pedagogy coursework while teaching full-time. Your district assigns a mentor who reviews your laboratory safety protocols weekly.

Emergency provisional hires often struggle most with classroom management. You learn formative assessment techniques while simultaneously managing 30 freshmen with scalpels.

The hard truths about those exams matter for your timeline. Praxis Biology Content Knowledge (5235) first-time pass rates hover between 65-75% nationally. Many candidates fail the cellular processes and genetics sections specifically.

I spent 6-8 weeks preparing using ETS practice tests ($19.95) and spaced-repetition flashcards. Plan for 90 minutes of study daily. If you fail, you wait 28 days and pay another $150 to retake. Three attempts max per year.

Beyond the ETS materials, Quizlet decks organized by Praxis code help. I drilled the 5235 deck during my commute. The $19.95 investment beats the $150 retake fee.

Reciprocity sounds simple but carries fine print that delays hiring. While 45 states participate in NASDTEC interstate agreements, transfers are not automatic. You still submit transcripts, pay fees, and wait.

California requires additional CTEL coursework (45 hours) if you land in ESL-heavy districts like LAUSD. Texas mandates the PPR exam (160+ score) regardless of your out-of-state experience. New York forces veteran teachers to submit edTPA portfolios even with ten years of inquiry-based learning units under their belts.

Florida skips the edTPA but demands a specific classroom management course. Research your target state's unique addons before you box up the lab equipment.

Consider the benefits of a Master's degree for career advancement before you start. Some states pay for it through grow-your-own programs. Districts offer tuition reimbursement ranging from $2k-5k annually.

Others require graduate credits within five years of hire to maintain your license. Advanced coursework deepens your understanding of Next Generation Science Standards and the scientific method itself. You learn to write better formative assessments.

Teaching science means proving you can guide students through the scientific method while keeping them safe. Your credential is the legal permission to do both. Start gathering transcripts now. The bureaucratic wheel turns slowly, and the application fee alone runs $200 in most states.

Proven Instructional Strategies for Engaging Science Learners

You can't teach photosynthesis with lectures alone. I learned that the hard way during my first year. A good science teacher needs multiple strategies because cellular respiration and atomic structure require different approaches.

John Hattie's research gives us hard numbers. Direct Instruction shows an effect size of d=0.59. Unguided Open Inquiry sits at d=0.30. That gap matters when you're planning Monday's lesson.

Direct Instruction: Thirty-minute prep, high structure, immediate feedback, low safety risk. The d=0.59 effect size makes it efficient for new content.

Open Inquiry: Ninety-minute prep, high autonomy, delayed guidance, elevated safety concerns. The d=0.30 drops further without proper scaffolding.

The safety risk jumps with inquiry. Novices burn themselves or misuse chemicals while you're troubleshooting group dynamics across the room. I once had a student add acid to water incorrectly during an open inquiry because I was helping another group across the lab.

The 5E Instructional Model balances both worlds. I used it last October with 7th graders studying cellular respiration. The sequence took seventy minutes total, broken into five chunks.

Engage started with a yeast balloon demo. Ten minutes of watching bread rise beats any textbook opener. Explore used bromothymol blue pH indicators with elodea in test tubes. That hands-on learning in the classroom showed CO2 production better than my diagrams ever could as kids watched the color shift from blue to yellow.

Explain followed with fifteen minutes of lecture connecting the demo to ATP equations. Elaborate had students compare photosynthesis and respiration equations side-by-side for another fifteen minutes.

Evaluate meant a CER exit ticket. Students claimed the yeast produced gas, cited the balloon data, and explained the cellular respiration equation. Ten minutes of formative assessment told me who needed reteaching.

For high school chemistry, I use POGIL—Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning. It works for Next Generation Science Standards alignment without the chaos of pure discovery. The structured activities build science learning through data analysis, replacing traditional lecture.

Students sit in fixed groups of four with assigned roles. The Manager keeps time, the Presenter speaks for the group, the Recorder writes, and the Reflector checks understanding. They work through Periodic Trends activities over two class periods—ninety minutes total.

Your job is asking "why" when they present answers, not giving solutions. I circulate with a clipboard, listening for pedagogical content knowledge gaps. If the Manager lets one student dominate, I pause the group. When the Recorder writes incomplete equations, I point to the data table.

Here's the hard truth. Direct instruction outperforms inquiry-based learning for students below the fiftieth percentile in reading comprehension. If they can't decode the lab instructions, they learn nothing from the activity.

Same with laboratory safety. Kids without prior technique training need explicit modeling first. They don't instinctively know how to use a pipette or read a meniscus. Save open inquiry for honors or AP classes with established safety protocol mastery and self-regulation skills.

When the scientific method feels stale, I supplement with educational games for STEM classrooms. But games don't replace the heavy lifting of learning science through structured inquiry.

Match the strategy to your learners' readiness. That's the difference between real science learning and just doing busywork.

How Do You Become a Science Teacher?

To become a science teacher, earn a bachelor's degree in science or education, complete a state-approved teacher preparation program with student teaching, pass required Praxis exams (Core and Subject Assessment), and apply for state licensure. Alternative certification routes exist for career changers with science degrees, typically requiring 5-8 weeks of intensive training and a provisional license.

Content credentials come first. You need either 60 semester hours of science courses or a Bachelor's in Secondary Science Education. Most universities require a 3.0 GPA to place you in student teaching. I started with the 4-year route, which builds your pedagogical content knowledge for teaching science effectively.

The 2-year pathway suits career changers who already hold a biology or chemistry degree. You transcript 60 science credits and add education courses focused on teaching science. The 4-year Bachelor's in Secondary Science Education mixes content with methods courses. Both paths require maintaining that 3.0 GPA through your junior year to qualify for placement.

Your coursework includes physics, chemistry, biology, and earth science regardless of which path you choose. You will dissect specimens, balance chemical equations, and study geology. Universities check that you have breadth across disciplines, not just depth in one area. This ensures you can teach middle school integrated science or high school biology with equal confidence.

Next, pass the required examinations. The Praxis Core Academic Skills tests require these minimum scores:

Reading: 156

Writing: 162

Math: 150

Then take your Praxis Subject Assessment—Biology: Content Knowledge (5235) requires a 154, or take General Science (5435). Budget $150-210 per exam plus $50-75 for study guides.

Schedule your Praxis exams during your junior year or early senior year. The Core tests your basic skills; the Subject Assessment digs into inquiry-based learning theory and content knowledge. Buy the official study guides. I failed the first writing attempt by two points and had to reschedule—budget time for retakes.

Some states accept alternative exams like NES or state-specific tests instead of Praxis. Check your Department of Education website before buying study materials. Register early—testing centers fill up in October when seniors book their slots. Bring a government ID and leave your phone in the car; they are strict about security.

Complete your state-approved teacher preparation program. This includes:

150 clock hours observing in classrooms

450 clock hours of supervised student teaching

3-hour Recognizing and Reporting Child Abuse certification

Both a university coordinator and your mentor teacher evaluate your instruction. You cannot graduate without completing all 600 hours.

Those 450 hours of student teaching mean you are the teacher. You write the lesson plans, grade the labs, and handle the classroom management while your mentor observes. My university coordinator visited four times to evaluate my use of the scientific method in lessons. You also complete that mandatory child safety training online before stepping into any classroom.

During my student teaching, I learned to prep solutions the night before and always have a non-lab backup lesson ready. The 150 observation hours come first—you watch your mentor teach units on genetics and cell division. Take notes on how they transition from lecture to lab activity smoothly without chaos.

Apply for state licensure ($75-200) and submit fingerprints ($50-75). Most states then require a 1-2 year induction program. Mine involved monthly observations with a mentor who helped me navigate laboratory safety protocols and formative assessment strategies during my first year.

Induction programs pair you with a veteran science teacher from your building. You meet weekly, and they observe your instruction monthly. You document your growth in areas like laboratory safety procedures and formative assessment techniques. Some states call this "initial licensure" or "Level 1" status until you finish the two years.

Keep all your receipts for licensure fees; some districts reimburse these during your first year. The background check takes two to eight weeks depending on your state. You cannot step into a classroom without cleared fingerprints. Start this process in April before graduation to avoid delays in your August start date.

Career changers can skip the traditional path. Programs like Teach For America or TNTP run 5-week summer institutes with 50 hours of practice teaching. You get a provisional license, teach full-time immediately, and must finish a master's degree within two years.

The alternative route is not easier. You attend the 5-week institute from 8 AM to 6 PM daily, teaching summer school students for those 50 hours. Then you start August with your own classroom and full course load. You have two years to complete a master's degree while teaching, which means taking night classes or online courses during the school year.

Many career changers choose this route during economic downturns or mid-career pivots. You earn a salary immediately while learning on the job. However, you must balance lesson planning with graduate coursework, which means late nights and weekends. Support systems matter—find other alternative-route teachers in your cohort to survive the first semester.

Whether you choose the traditional or alternative route, prioritize understanding the Next Generation Science Standards and inquiry-based learning frameworks. Your modern teacher preparation should include classroom management for labs, not just theory. The first year is tough, but the credential opens doors to a career where you actually get to do experiments with kids every day.

Science Teacher: The 3-Step Kickoff

Teaching science means managing controlled chaos. You’ll juggle chemical inventories, hunt for missing goggles, and calm teenagers who think fire constitutes an experiment. But when a student connects photosynthesis to their wilting houseplant, that noise fades. You’re not just checking off Next Generation Science Standards; you’re building skeptics who trust evidence over clicks. Focus on pedagogical content knowledge—knowing why students confuse velocity with acceleration—not just facts.

Start exactly where you are. If you’re already in the classroom, pilot one inquiry-based learning protocol next month. If you’re earning credentials, shadow a teacher during lab setup week. Your first year feels like survival mode. Lock down laboratory safety routines until they’re automatic, then layer in the creative labs. Students remember the teacher who kept them safe and asked hard questions.

Audit your lab safety procedures against state guidelines this weekend.

Draft one inquiry-based unit using only materials already in your supply closet.

Email a veteran science teacher to request an observation during their messiest lab day.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.