Hands-On Learning: Complete Guide for K-12 Classrooms

Hands-On Learning: Complete Guide for K-12 Classrooms

Hands-On Learning: Complete Guide for K-12 Classrooms

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

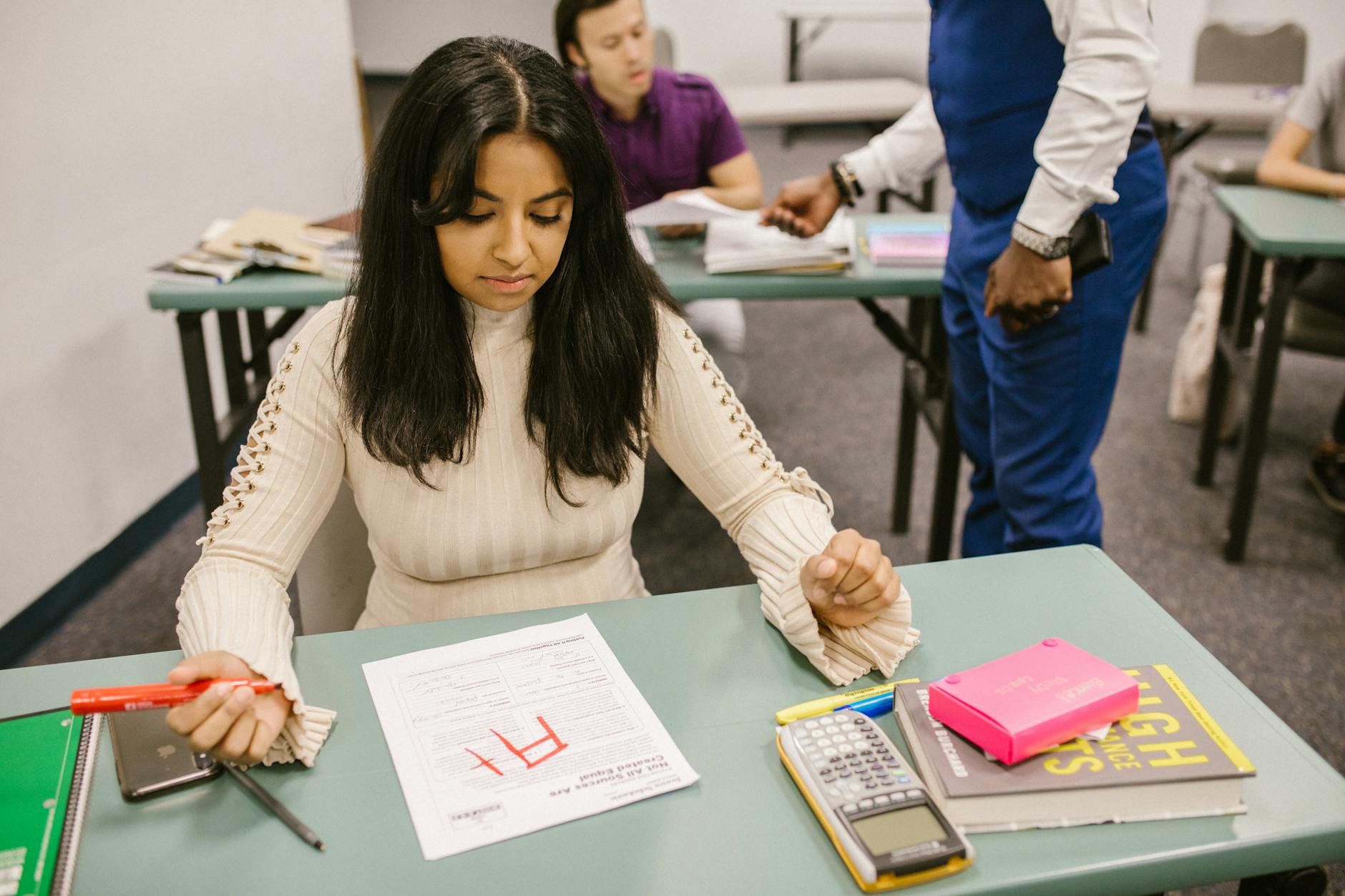

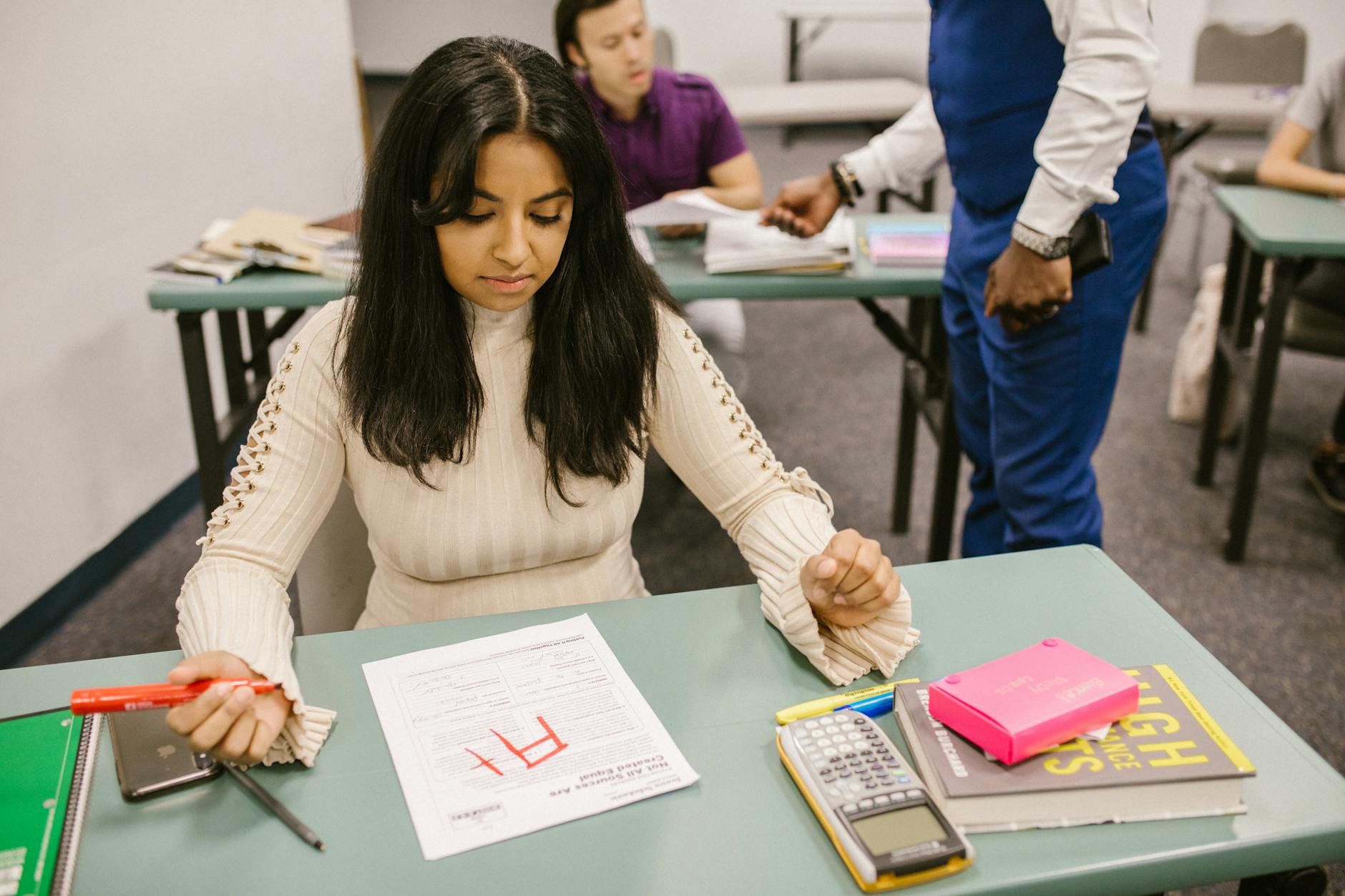

Hands-on learning puts physical materials in students' hands so they build understanding through touch and experimentation. Unlike passive instruction where kids sit and receive information, this approach demands they manipulate objects and construct meaning themselves. It's the difference between watching someone swim and jumping in the pool.

You know the moment. You explain regrouping to your 3rd graders, but the blank stares don't clear until a student trades ten unit cubes for a ten-rod. That click is hands on learning.

This is experiential education through Kolb's cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Students use manipulatives to build understanding. John Hattie's Visible Learning shows direct instruction carries an effect size of 0.59, but hands-on learning combines physical action with cognitive processing.

Hands-on learning puts physical materials in students' hands so they build understanding through touch and experimentation. Unlike passive instruction where kids sit and receive information, this approach demands they manipulate objects and construct meaning themselves. It's the difference between watching someone swim and jumping in the pool.

You know the moment. You explain regrouping to your 3rd graders, but the blank stares don't clear until a student trades ten unit cubes for a ten-rod. That click is hands on learning.

This is experiential education through Kolb's cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Students use manipulatives to build understanding. John Hattie's Visible Learning shows direct instruction carries an effect size of 0.59, but hands-on learning combines physical action with cognitive processing.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

What Is Hands-On Learning and How Does It Differ From Passive Instruction?

Here's how active and passive learning models differ:

Passive: Lecture. 5-10% retention. Teacher delivers; students observe.

Active: Discussion. Moderate retention. Teacher facilitates verbal processing.

Hands-On: Tactile manipulation. High retention through sensory encoding. Teacher guides building.

Unlike watching a demonstration, physically trading cubes for rods creates sensory-motor pathways. The child explains regrouping because they've felt the quantity shift.

Defining Experiential and Kinesthetic Instruction

Kolb's cycle requires doing. My 5th graders discovered photosynthesis not by reading, but by growing beans in darkness versus sun. They observed, reflected, conceptualized, then engaged in inquiry-based learning by testing variables.

This differs from kinesthetic activities serving only "kinesthetic learners." Fleming's VAK model describes preferences, not requirements. During Piaget's Concrete Operational Stage (ages 7-11), all children need physical manipulation to grasp abstractions like fractions.

Hands-On Learning vs. Active and Passive Learning Models

Passive Instruction offers efficiency and low cost, but minimal retention. Active Discussion builds communication, yet demands wait-time. Project-based learning through hands-on manipulation achieves high retention through constructivism, though it requires prep time.

Rosenshine's Principles remind us that hands-on learning fails as pure discovery. It succeeds with clear models and guided practice. You demonstrate first, then let them manipulate materials while you check understanding.

Ask "what would happen if." In hands-on learning, students reference physical experience: "When I pushed the magnet, it repelled." In passive instruction, they search notes. One uses embodied knowledge; the other, memory.

Why Does Hands-On Learning Improve Student Retention and Engagement?

Research suggests hands on learning improves retention because it engages multiple cognitive pathways simultaneously, creating stronger neural connections. When students physically manipulate materials, they activate sensory and motor cortices alongside memory centers, resulting in deeper encoding than auditory or visual input alone, particularly for procedural and spatial knowledge.

You remember what you do. That simple truth explains why students recall labs they performed but forget the PowerPoints you spent hours perfecting.

John Hattie's meta-analysis shows instructional quality matters more than method, yet hands-on approaches show stronger effect sizes for procedural knowledge and spatial reasoning. Physical manipulation adds value where abstract concepts meet real space.

The encoding specificity principle means students encode memories with sensorimotor context. They recall better when assessments match that original physical context. A student who built a circuit remembers during a performance task, not just on a test.

Dual coding theory (Paivio) creates both verbal and nonverbal memory traces. You get two hooks into memory instead of one. This aligns with constructivism — knowledge built through physical interaction.

Hands-on science instruction correlates with higher performance on inquiry-based learning assessments compared to lecture-only controls. Students who manipulate variables retain experimental logic longer.

Cognitive Science Behind Experiential Education

Working memory has limits. Physical manipulatives reduce cognitive load by externalizing abstract relationships. I watched my 2nd graders struggle with mental math last fall until they used physical number paths. The objects held the information so their minds could focus on the concepts.

The enactive learning framework aligns with constructivism, describing knowledge beginning as motor actions before becoming representational. These students struggle with abstract number lines until they walk physical paths. The body understands before the mind abstracts.

Haptic feedback provides data visual learning cannot. Touch conveys weight and resistance. Students understand density when hefting equal volumes of wood and metal, anchoring abstract definitions in physical reality.

Engagement Metrics Compared to Lecture-Based Instruction

Kinesthetic activities typically produce 85-90% on-task rates versus 60-70% during extended direct instruction. These numbers depend on classroom management quality. A well-run lecture beats a chaotic lab.

But engagement predicts achievement only when you distinguish "messing about" from intentional learning. Project-based learning and active teaching and learning strategies require clear objectives and reflection protocols. Building bridges without understanding load-bearing principles is just play.

Time-on-task differs significantly. Hands-on activities need 15-20 minutes for full engagement as students iterate. Lectures hit optimal attention at 5-7 minutes. See our experiential education implementation guide for pacing strategies.

How Does the Brain Process Information During Hands-On Activities?

During hands on learning, the brain processes information through the somatosensory cortex receiving tactile input, which then connects to the prefrontal cortex for executive function and the hippocampus for memory formation. This multisensory activation creates richer neural networks and stronger memory traces than single-modality learning experiences.

When your students snap together manipulatives or pour water into beakers, their mechanoreceptors fire first. Merkel cells and Meissner corpuscles in the skin detect texture and pressure, shooting signals up the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway to the postcentral gyrus. That is the somatosensory cortex lighting up.

From there, the signal splits. One branch hits the prefrontal cortex for executive function—planning the next move, adjusting grip. The other forks to the hippocampus for memory consolidation. This hands to mind route explains why a student remembers building a volcano better than reading about one.

Research on embodied cognition shows that physical manipulation wakes up the same mirror neuron systems we use for complex reasoning. That is why students who gesture while solving math problems score higher—their hands are thinking. This applies to project-based learning and inquiry-based learning alike. The intraparietal sulcus integrates tactile and visual input during these tasks, making it critical for STEM learning.

Jerome Bruner's constructivism research gives us the concrete-pictorial-abstract progression. Physical manipulation builds neural scaffolds necessary for abstract symbol manipulation. Without that concrete foundation, students rely on instrumental understanding—mere memorization—while missing relational comprehension. Check our brain-based teaching guide for more on this sequence.

The Neurological Pathway From Hands to Mind

The journey starts at the fingertips. Merkel cells detect sustained pressure while Meissner corpuscles sense texture and vibration. These signals travel the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway to the postcentral gyrus in the parietal lobe.

This is where cross-modal plasticity kicks in. When students watch their hands work, they activate both the somatosensory cortex and the visual cortex. That dual activation creates stronger interhemispheric connections than unimodal learning ever could.

Timing matters. The motor cortex activates 200-400 milliseconds before conscious awareness. This means students physically test solutions before they can verbalize them. I watched this with my 7th graders modeling tectonic plates with foam blocks. Their hands predicted subduction before their mouths could explain it.

Concrete to Abstract Concept Formation

Bruner's CPA approach is not just pedagogy—it is neuroscience. First graders need three weeks of kinesthetic activities before they can handle equations. The progression follows three distinct stages:

Concrete: Students compose and decompose numbers using linking cubes.

Pictorial: They draw representations of the cube structures.

Abstract: Finally, they write the numerical equations.

Most students need five to seven concrete experiences to internalize a mental model. High schoolers might need only two or three repetitions, but elementary students often need eight to ten. Rush this sequence, and students develop instrumental understanding—mere memorization—while missing relational comprehension.

Skip the manipulatives, and you lose the neural architecture for abstract reasoning. Experiential education through physical objects prevents this gap.

What Are the Essential Elements of Effective Hands-On Lessons?

Effective hands-on lessons require four core elements: physical manipulatives that represent abstract concepts, student-driven inquiry with minimal initial direction, authentic real-world problem contexts, and structured reflection protocols. These components transform mere activity into intentional learning experiences with measurable outcomes.

Activity without structure is just noise. You need four specific ingredients to make hands on learning stick, or you'll waste 40 minutes and end up with glitter on the floor and no learning gains.

Check your lessons against this list:

Physical manipulatives that represent abstract concepts. Red flag: Using toys that distract from the learning target.

Student-driven inquiry protocols. Red flag: Giving step-by-step instructions that remove the thinking.

Authentic real-world contexts. Red flag: Using fake scenarios students cannot relate to.

Structured reflection time. Red flag: Skipping the debrief because you ran out of time.

Budget reality check: effective experiential education requires an initial investment of $50 to $200 per classroom for durable materials, plus ongoing costs of $0.50 to $2.00 per student for consumables.

Protect this rhythm in a 40-minute period: 5 minutes for setup, 20 minutes for exploration, 10 minutes for discussion, and 5 minutes for cleanup and reflection. This honors constructivism while keeping your sanity.

The 5E Instructional Model organizes these elements: Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate. It prevents lecturing before students touch materials, which kills inquiry-based learning.

Physical Manipulatives and Tactile Materials

Stock five essential categories: measurement tools ($25-40 per set), building systems like Brackitz ($80-150), natural specimens (free), craft consumables ($0.30 per student), and digital probes ($100-200). These tactile learning and physical manipulatives make abstract concepts concrete.

Storage determines longevity. Use compartmentalized hardware boxes ($12 each) for small parts, labeled ziplock bags for consumables, and strict check-out protocols to prevent the "lost magnet" conversation.

Safety varies by age. Use non-toxic materials for PreK-2, blunt tools for grades 3-5, and precision instruments for 6-12. Keep MSDS sheets filed for chemicals, and read them before the fire marshal visits.

Student-Driven Inquiry and Exploration

Apply the 5E structure with discipline: Engage with a discrepancy event, Explore through hands-on investigation without direct instruction, Explain by having students articulate findings, Elaborate by extending to new contexts, and Evaluate through formative assessment. This framework separates kinesthetic activities from busy work.

Questioning makes the difference. Use 3-5 seconds of wait time after open-ended questions. Ask "What do you notice?" before "What do you think?" to drive observation, not guesswork.

Manage the messy middle. Allow 10 minutes of productive struggle before intervening. Enforce the "ask three before me" rule so students build independence. I learned this with my 7th graders during bridge-building—when I stopped hovering, they started solving.

Real-World Problem-Solving Contexts

Design constraints force creative thinking. Challenge 7th graders to build bridges with a $5 budget using only index cards and tape, requiring calculation of load-to-cost ratios. This turns project-based learning into engineering practice.

Authentic audiences raise the stakes. Have students present recycling sorting machines to custodial staff, share historical artifacts with museum docents, or demonstrate physics principles to younger students. Real eyes create real accountability.

Apply the "so what?" test. Students must articulate how the activity connects to a career, community issue, or daily life application. If they cannot answer, you have an activity, not experiential education.

Structured Reflection and Processing Time

Implement the 3-2-1 protocol: students record 3 things learned, 2 questions remaining, and 1 connection to prior knowledge in lab notebooks with sketches. This written component cements the learning.

Protect the final 7 minutes of every lesson for reflection. Learning consolidates during this processing window, not during the frantic activity itself. Skip this, and you lose 40% of the retention.

Differentiate exit tickets by age. Kindergarteners draw what happened. Third graders draw and label. High schoolers diagram with arrows showing cause and effect. Everyone processes, but the complexity scales with maturity.

How Can You Apply Hands-On Learning Across Different Subjects?

Hands-on learning applies across subjects by adapting the core principle of physical manipulation to content goals: using algebra tiles and probability simulators in math, reader's theater and tactile story maps in literacy, archaeological digs and mock trials in social studies, and stop-motion animation or clay modeling in arts.

Stop treating subjects as silos. When you align manipulatives and kinesthetic activities to specific standards, you transform every content area into a laboratory for discovery.

Subject | Hands-On Method | Grade Example | Cost | Standard Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mathematics | Cuisenaire rods for number relationships | Grade 1 | $15 | 1.OA.A.1 |

Literacy | Felt boards for story retelling | Grade 2 | $20 | CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.5 |

Social Studies | Archaeological dig simulation | Grade 5 | $50 | NCSS.D2.His.3.3-5 |

Arts | Stop-motion clay animation | Grade 6 | $10 | NA-VA.5-8.2 |

Cross-curricular projects maximize your planning time. Last spring, my fifth graders built scale models of state landmarks using foam core and hot glue. They calculated proportions using CCSS 4.NF.2 fraction comparisons, researched geographic significance for social studies, and drafted blueprints fulfilling art design standards. One project, three subjects.

STEM and Mathematics Applications

Mathematics K-2: Cuisenaire rods for number sense ($15 per class set), pattern blocks for geometry ($12).

Mathematics 3-5: Fraction towers for equivalence ($25), base-ten blocks for decimals ($30), targeting CCSS 4.NF.2.

Mathematics 6-8: Algebra tiles for solving equations ($35), probability spinners and dice ($5). Science classes address MS-PS1-1 through particle modeling.

Literacy and Language Arts Strategies

Early readers retell stories using felt characters and settings on bulletin boards, building sight words with magnetic letters. Third through fifth graders create blackout poetry using discarded newspaper articles, physically isolating themes and tone. Sixth through eighth graders freeze into dramatic tableaux of Shakespeare scenes using costume pieces to embody subtext. Tactile story maps using sandpaper for rough settings engage multiple senses during analysis. These experiential education techniques cement comprehension through physical interaction with text, avoiding passive consumption.

Social Studies and Historical Simulations

5th grade: Archaeological dig in sandbox with stratified layers representing different historical periods, using proper tools like brushes and trowels.

8th grade: Mock Constitutional Convention with assigned roles, period-appropriate seating arrangement, and parliamentary procedure.

High school: Stock market simulation with physical currency and ticker tape, or UN Security Council debates with placards and resolution drafting.

Arts and Creative Expression Projects

Elementary students use iStopMotion ($9.99) and clay modeling to animate historical events or book plots, combining digital literacy with tactile creation. Middle schoolers construct found-object sculptures representing geometric shapes or chemical compounds, merging integrative STEM education with artistic vision. High school theater students build set design scale models using foam core and hot glue, calculating proportions and perspective. These project-based learning approaches demonstrate that art studios function as rigorous academic spaces where hands on learning meets aesthetic discipline.

What Are the Most Common Mistakes Teachers Make With Hands-On Learning?

Teachers often mistake hands-on learning for mere entertainment, failing to align activities with specific learning objectives. Common errors include launching complex projects without adequate scaffolding, neglecting safety protocols during science labs, and assessing the product rather than the learning process, resulting in missed educational outcomes.

Busywork disguised as experiential education wastes instructional time. Watch for these red flags before your next project-based learning unit.

Red flag: Students ask "what do I do next?" instead of "what happens if?" Fix: Use backward design starting with the standard.

Red flag: Cleanup takes longer than the learning activity. Fix: Implement the "leave no trace" rule with photo evidence.

Red flag: You spend 30 minutes prepping for 15 minutes of student work. Fix: Simplify materials or switch to digital simulations.

Red flag: Early finishers disrupt others while waiting. Fix: Create extension tasks or cleanup duties.

Confusing Activity With Actual Learning Objectives

When students ask "what do I do next?" instead of "what happens if?", you have recipe-following, not inquiry-based learning. This signals activity-based instruction masquerading as hands on learning.

Apply backward design starting with the standard. If students can complete the task without grasping the concept, redesign it. I watched 4th graders build marshmallow towers once. They had fun. But when I asked about tension versus compression, they stared at me. The manipulatives became toys, not tools. Ensure the activity requires understanding the concept to succeed. Otherwise, you are wasting 30 minutes of prep for 15 minutes of engagement. The "fun over function" trap kills educational value every time.

Insufficient Scaffolding for Complex Tasks

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development matters here. If students cannot complete the task with minimal guidance, your scaffold is missing. Handing 6th graders electronics kits without teaching series and parallel circuits first creates chaos. They guess. They do not construct. Nothing teaches resignation like impossible tasks.

Use the gradual release model over three lessons. First, "I do" with teacher demonstration. Then "we do" using templates and guided practice. Finally, "you do" allows independent exploration. This prevents frustration while honoring constructivism. Never drop complex kinesthetic activities without foundational skills. Students need the "we do" phase to bridge the gap between watching and doing successfully.

Neglecting Safety and Classroom Management Protocols

Lack of classroom management strategies turns labs into liability nightmares. Require signed safety contracts for chemicals. Mandate eye protection for 5th grade and up. Post material safety data sheets visibly near the supply station. Never skip the safety talk, even for "safe" household items.

Material distribution fails when you hand items to each student. Instead, assign table captains to retrieve supplies from designated stations. For early finishers, post a "before" photo of the clean station. Students cannot line up until their desk matches the image. This "leave no trace" rule prevents cleanup from exceeding learning time. If washing beakers takes longer than the experiment itself, redesign the workflow immediately.

Failure to Connect Activities to Assessment Criteria

Grading the poster's artistic quality while ignoring scientific accuracy misses the point. Separate your rubric into three categories: Scientific Understanding (40%), Procedure Following (30%), and Presentation (30%). This prevents the "fun over function" trap where students build baking soda volcanoes that erupt spectacularly without knowing about chemical reactions or plate tectonics. The eruption becomes mere entertainment, not evidence of learning.

Insert formative checkpoints during long-term project-based learning. Without them, misconceptions solidify and students wander off-task for days. If the product looks great but the student cannot explain the underlying concept, you have craft time, not science class. Assess the learning process through observation and questioning, not just the final display. Check understanding while they work, not only when they finish.

How Do You Assess Student Learning During Hands-On Activities?

Assessment during hands-on learning relies on authentic observation using protocols like the Primary Trait Analysis, student-maintained inquiry notebooks with date-stamped entries, and performance rubrics evaluating both process skills and content mastery. These methods capture learning as it happens without relying solely on post-activity tests.

You cannot grade a lab like a worksheet.

Choose your method based on your goal. Use observation for process skills during kinesthetic activities. Use documentation for inquiry-based learning tracking. Use performance assessment for project-based learning final products.

Watch four or five students deeply each lesson instead of scanning the whole room. Carry a clipboard with time-stamped notes. Rotate through your roster every three to four days. Deep data beats shallow checkmarks.

The thinking is invisible. Capture it by photographing work at ten-minute intervals. Record direct quotes of student speech during manipulatives work. These artifacts show the reasoning behind the final product.

Observation Protocols and Anecdotal Checklists

Use Primary Trait Analysis to stay focused. Pick three specific behaviors—"measures accurately," "controls variables," "makes predictions"—and tally frequency.

Keep a class roster with time-stamped anecdotal notes recording direct quotes of student speech during exploration.

Use your tablet to photograph student work at ten-minute intervals, creating a time-lapse of problem-solving. Keep digital permission slips on file.

I learned this with my 7th graders last spring. I tried watching everyone and missed Marcus misreading the cylinder for fifteen minutes. Now I focus on five students and catch errors early.

Student Documentation and Lab Notebook Methods

Require lab notebooks with date, question, prediction, procedure sketch, data table, and conclusion. Check these daily, not at unit end. The sketch reveals understanding better than paragraphs.

Provide sentence stems for ELL students ("I observed..."). Allow voice-to-text for dysgraphic students or video explanations for reluctant writers. Have students list three safety precautions before starting, initialing each as they follow them during the activity.

Performance-Based Rubrics and Presentations

Design a 4-point rubric: Novice needs constant guidance, Apprentice completes with hints, Proficient succeeds independently, Distinguished extends to new contexts. See our performance-based assessment guide for calibration.

Use "2 stars and 1 wish" for peer review—two compliments and one suggestion using sentence frames. Require a three-minute "science talk" where students defend design choices using evidence. This reveals experiential education and constructivism in action.

What Is the Fastest Way to Start Using Hands-On Learning Tomorrow?

Start hands-on learning tomorrow by selecting one concrete standard suitable for manipulation, gathering found materials like recyclables or nature items, designing a simple three-step protocol with explicit objectives, and preparing management logistics including safety briefings and five-minute reflection time.

You do not need a grant. You need ninety minutes tonight and a garbage bag. Pick one standard, grab some tape and cardboard, and write one sentence describing what students will physically demonstrate. That is your entire plan.

Identify One Standard Suitable for Experiential Learning

Look for verbs that imply doing, not just knowing. Search NGSS for "develop a model" or CCSS Math for "understand" rather than "fluently compute." These indicate standards suitable for experiential education and manipulation.

Kindergarten K-PS2-1 works beautifully—students pushing toy cars to test push and pull forces. Seventh grade 7.RP.A.2 clicks when kids mix paint colors to explore proportional relationships. Biology LS1-2 comes alive with simple egg osmosis experiments.

Avoid standards demanding rote memorization like state capitals or pure computation like multi-digit multiplication algorithms for your first attempt. You want students constructing meaning through constructivism, not just retrieving facts from flashcards.

Gather Low-Cost or Found Materials

Raid your recycling bin first. Paper towel tubes become marble runs. Egg cartons sort manipulatives. Cereal boxes transform into building blocks for towers. Nature provides free supplies for inquiry-based learning: sticks for measurement, leaves for classification, rocks for geology observation.

Dig into your desk drawers. Paper clips create chain reactions. Sticky notes categorize ideas. Rulers and timers collect real data.

Total cost runs zero to five dollars. I once taught a full forces and motion unit to 8th graders using only dried beans as weights, scrap cardboard, and string from the art room. The simplicity actually forced clearer thinking about the physics concepts.

Design a Simple Protocol With Clear Objectives

Map twenty minutes exactly. Two minutes for a hook or discrepant event. Ten minutes for exploration with a "must test three variations" requirement. Five minutes for share-out using your document camera. Three minutes for an exit ticket.

Write the learning target on the board: "I can demonstrate how [concept] works by [action]." Keep it visible throughout this kinesthetic activity.

List three safety rules on the board before you start: materials stay on the tray, voice level two, stop when the signal sounds. Have students repeat them back. Use our lesson plan template and setup guide to structure this protocol without overthinking.

Plan for Management, Safety, and Reflection

Prep stations the night before. Place all materials in baskets with cleanup supplies—sponges and paper towels included. Nothing kills momentum like hunting for a rag with glue on your fingers.

Create one "extension challenge" card for early finishers. It keeps them testing variables while others catch up, preventing disruption.

Place sticky notes and pencils at each table before students arrive. If reflection tools are not ready, the five-minute closing reflection vanishes when the bell rings. This hands on learning cycle demands that students articulate what their fingers discovered before they leave the room.

Hands On Learning: The 3-Step Kickoff

You have enough theory. You know that experiential education sticks better than worksheets, and you have seen how manipulatives turn abstract symbols into something a kid can touch. The hard part is starting without rewriting your entire curriculum. That is where teachers get stuck. They picture a complete overhaul and freeze.

Stop aiming for perfect. Pick one lesson for tomorrow. Swap the passage-reading or the lecture notes for an object students can break, build, or sort. Let the content get a little noisy. The learning happens in that noise—not in the silence of a quiet worksheet.

Choose one standard from your next unit.

Find one physical object that represents the core idea.

Write one inquiry-based question to launch the activity.

Set a timer for ten minutes and say nothing while they figure it out.

What Is Hands-On Learning and How Does It Differ From Passive Instruction?

Here's how active and passive learning models differ:

Passive: Lecture. 5-10% retention. Teacher delivers; students observe.

Active: Discussion. Moderate retention. Teacher facilitates verbal processing.

Hands-On: Tactile manipulation. High retention through sensory encoding. Teacher guides building.

Unlike watching a demonstration, physically trading cubes for rods creates sensory-motor pathways. The child explains regrouping because they've felt the quantity shift.

Defining Experiential and Kinesthetic Instruction

Kolb's cycle requires doing. My 5th graders discovered photosynthesis not by reading, but by growing beans in darkness versus sun. They observed, reflected, conceptualized, then engaged in inquiry-based learning by testing variables.

This differs from kinesthetic activities serving only "kinesthetic learners." Fleming's VAK model describes preferences, not requirements. During Piaget's Concrete Operational Stage (ages 7-11), all children need physical manipulation to grasp abstractions like fractions.

Hands-On Learning vs. Active and Passive Learning Models

Passive Instruction offers efficiency and low cost, but minimal retention. Active Discussion builds communication, yet demands wait-time. Project-based learning through hands-on manipulation achieves high retention through constructivism, though it requires prep time.

Rosenshine's Principles remind us that hands-on learning fails as pure discovery. It succeeds with clear models and guided practice. You demonstrate first, then let them manipulate materials while you check understanding.

Ask "what would happen if." In hands-on learning, students reference physical experience: "When I pushed the magnet, it repelled." In passive instruction, they search notes. One uses embodied knowledge; the other, memory.

Why Does Hands-On Learning Improve Student Retention and Engagement?

Research suggests hands on learning improves retention because it engages multiple cognitive pathways simultaneously, creating stronger neural connections. When students physically manipulate materials, they activate sensory and motor cortices alongside memory centers, resulting in deeper encoding than auditory or visual input alone, particularly for procedural and spatial knowledge.

You remember what you do. That simple truth explains why students recall labs they performed but forget the PowerPoints you spent hours perfecting.

John Hattie's meta-analysis shows instructional quality matters more than method, yet hands-on approaches show stronger effect sizes for procedural knowledge and spatial reasoning. Physical manipulation adds value where abstract concepts meet real space.

The encoding specificity principle means students encode memories with sensorimotor context. They recall better when assessments match that original physical context. A student who built a circuit remembers during a performance task, not just on a test.

Dual coding theory (Paivio) creates both verbal and nonverbal memory traces. You get two hooks into memory instead of one. This aligns with constructivism — knowledge built through physical interaction.

Hands-on science instruction correlates with higher performance on inquiry-based learning assessments compared to lecture-only controls. Students who manipulate variables retain experimental logic longer.

Cognitive Science Behind Experiential Education

Working memory has limits. Physical manipulatives reduce cognitive load by externalizing abstract relationships. I watched my 2nd graders struggle with mental math last fall until they used physical number paths. The objects held the information so their minds could focus on the concepts.

The enactive learning framework aligns with constructivism, describing knowledge beginning as motor actions before becoming representational. These students struggle with abstract number lines until they walk physical paths. The body understands before the mind abstracts.

Haptic feedback provides data visual learning cannot. Touch conveys weight and resistance. Students understand density when hefting equal volumes of wood and metal, anchoring abstract definitions in physical reality.

Engagement Metrics Compared to Lecture-Based Instruction

Kinesthetic activities typically produce 85-90% on-task rates versus 60-70% during extended direct instruction. These numbers depend on classroom management quality. A well-run lecture beats a chaotic lab.

But engagement predicts achievement only when you distinguish "messing about" from intentional learning. Project-based learning and active teaching and learning strategies require clear objectives and reflection protocols. Building bridges without understanding load-bearing principles is just play.

Time-on-task differs significantly. Hands-on activities need 15-20 minutes for full engagement as students iterate. Lectures hit optimal attention at 5-7 minutes. See our experiential education implementation guide for pacing strategies.

How Does the Brain Process Information During Hands-On Activities?

During hands on learning, the brain processes information through the somatosensory cortex receiving tactile input, which then connects to the prefrontal cortex for executive function and the hippocampus for memory formation. This multisensory activation creates richer neural networks and stronger memory traces than single-modality learning experiences.

When your students snap together manipulatives or pour water into beakers, their mechanoreceptors fire first. Merkel cells and Meissner corpuscles in the skin detect texture and pressure, shooting signals up the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway to the postcentral gyrus. That is the somatosensory cortex lighting up.

From there, the signal splits. One branch hits the prefrontal cortex for executive function—planning the next move, adjusting grip. The other forks to the hippocampus for memory consolidation. This hands to mind route explains why a student remembers building a volcano better than reading about one.

Research on embodied cognition shows that physical manipulation wakes up the same mirror neuron systems we use for complex reasoning. That is why students who gesture while solving math problems score higher—their hands are thinking. This applies to project-based learning and inquiry-based learning alike. The intraparietal sulcus integrates tactile and visual input during these tasks, making it critical for STEM learning.

Jerome Bruner's constructivism research gives us the concrete-pictorial-abstract progression. Physical manipulation builds neural scaffolds necessary for abstract symbol manipulation. Without that concrete foundation, students rely on instrumental understanding—mere memorization—while missing relational comprehension. Check our brain-based teaching guide for more on this sequence.

The Neurological Pathway From Hands to Mind

The journey starts at the fingertips. Merkel cells detect sustained pressure while Meissner corpuscles sense texture and vibration. These signals travel the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway to the postcentral gyrus in the parietal lobe.

This is where cross-modal plasticity kicks in. When students watch their hands work, they activate both the somatosensory cortex and the visual cortex. That dual activation creates stronger interhemispheric connections than unimodal learning ever could.

Timing matters. The motor cortex activates 200-400 milliseconds before conscious awareness. This means students physically test solutions before they can verbalize them. I watched this with my 7th graders modeling tectonic plates with foam blocks. Their hands predicted subduction before their mouths could explain it.

Concrete to Abstract Concept Formation

Bruner's CPA approach is not just pedagogy—it is neuroscience. First graders need three weeks of kinesthetic activities before they can handle equations. The progression follows three distinct stages:

Concrete: Students compose and decompose numbers using linking cubes.

Pictorial: They draw representations of the cube structures.

Abstract: Finally, they write the numerical equations.

Most students need five to seven concrete experiences to internalize a mental model. High schoolers might need only two or three repetitions, but elementary students often need eight to ten. Rush this sequence, and students develop instrumental understanding—mere memorization—while missing relational comprehension.

Skip the manipulatives, and you lose the neural architecture for abstract reasoning. Experiential education through physical objects prevents this gap.

What Are the Essential Elements of Effective Hands-On Lessons?

Effective hands-on lessons require four core elements: physical manipulatives that represent abstract concepts, student-driven inquiry with minimal initial direction, authentic real-world problem contexts, and structured reflection protocols. These components transform mere activity into intentional learning experiences with measurable outcomes.

Activity without structure is just noise. You need four specific ingredients to make hands on learning stick, or you'll waste 40 minutes and end up with glitter on the floor and no learning gains.

Check your lessons against this list:

Physical manipulatives that represent abstract concepts. Red flag: Using toys that distract from the learning target.

Student-driven inquiry protocols. Red flag: Giving step-by-step instructions that remove the thinking.

Authentic real-world contexts. Red flag: Using fake scenarios students cannot relate to.

Structured reflection time. Red flag: Skipping the debrief because you ran out of time.

Budget reality check: effective experiential education requires an initial investment of $50 to $200 per classroom for durable materials, plus ongoing costs of $0.50 to $2.00 per student for consumables.

Protect this rhythm in a 40-minute period: 5 minutes for setup, 20 minutes for exploration, 10 minutes for discussion, and 5 minutes for cleanup and reflection. This honors constructivism while keeping your sanity.

The 5E Instructional Model organizes these elements: Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate. It prevents lecturing before students touch materials, which kills inquiry-based learning.

Physical Manipulatives and Tactile Materials

Stock five essential categories: measurement tools ($25-40 per set), building systems like Brackitz ($80-150), natural specimens (free), craft consumables ($0.30 per student), and digital probes ($100-200). These tactile learning and physical manipulatives make abstract concepts concrete.

Storage determines longevity. Use compartmentalized hardware boxes ($12 each) for small parts, labeled ziplock bags for consumables, and strict check-out protocols to prevent the "lost magnet" conversation.

Safety varies by age. Use non-toxic materials for PreK-2, blunt tools for grades 3-5, and precision instruments for 6-12. Keep MSDS sheets filed for chemicals, and read them before the fire marshal visits.

Student-Driven Inquiry and Exploration

Apply the 5E structure with discipline: Engage with a discrepancy event, Explore through hands-on investigation without direct instruction, Explain by having students articulate findings, Elaborate by extending to new contexts, and Evaluate through formative assessment. This framework separates kinesthetic activities from busy work.

Questioning makes the difference. Use 3-5 seconds of wait time after open-ended questions. Ask "What do you notice?" before "What do you think?" to drive observation, not guesswork.

Manage the messy middle. Allow 10 minutes of productive struggle before intervening. Enforce the "ask three before me" rule so students build independence. I learned this with my 7th graders during bridge-building—when I stopped hovering, they started solving.

Real-World Problem-Solving Contexts

Design constraints force creative thinking. Challenge 7th graders to build bridges with a $5 budget using only index cards and tape, requiring calculation of load-to-cost ratios. This turns project-based learning into engineering practice.

Authentic audiences raise the stakes. Have students present recycling sorting machines to custodial staff, share historical artifacts with museum docents, or demonstrate physics principles to younger students. Real eyes create real accountability.

Apply the "so what?" test. Students must articulate how the activity connects to a career, community issue, or daily life application. If they cannot answer, you have an activity, not experiential education.

Structured Reflection and Processing Time

Implement the 3-2-1 protocol: students record 3 things learned, 2 questions remaining, and 1 connection to prior knowledge in lab notebooks with sketches. This written component cements the learning.

Protect the final 7 minutes of every lesson for reflection. Learning consolidates during this processing window, not during the frantic activity itself. Skip this, and you lose 40% of the retention.

Differentiate exit tickets by age. Kindergarteners draw what happened. Third graders draw and label. High schoolers diagram with arrows showing cause and effect. Everyone processes, but the complexity scales with maturity.

How Can You Apply Hands-On Learning Across Different Subjects?

Hands-on learning applies across subjects by adapting the core principle of physical manipulation to content goals: using algebra tiles and probability simulators in math, reader's theater and tactile story maps in literacy, archaeological digs and mock trials in social studies, and stop-motion animation or clay modeling in arts.

Stop treating subjects as silos. When you align manipulatives and kinesthetic activities to specific standards, you transform every content area into a laboratory for discovery.

Subject | Hands-On Method | Grade Example | Cost | Standard Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mathematics | Cuisenaire rods for number relationships | Grade 1 | $15 | 1.OA.A.1 |

Literacy | Felt boards for story retelling | Grade 2 | $20 | CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.5 |

Social Studies | Archaeological dig simulation | Grade 5 | $50 | NCSS.D2.His.3.3-5 |

Arts | Stop-motion clay animation | Grade 6 | $10 | NA-VA.5-8.2 |

Cross-curricular projects maximize your planning time. Last spring, my fifth graders built scale models of state landmarks using foam core and hot glue. They calculated proportions using CCSS 4.NF.2 fraction comparisons, researched geographic significance for social studies, and drafted blueprints fulfilling art design standards. One project, three subjects.

STEM and Mathematics Applications

Mathematics K-2: Cuisenaire rods for number sense ($15 per class set), pattern blocks for geometry ($12).

Mathematics 3-5: Fraction towers for equivalence ($25), base-ten blocks for decimals ($30), targeting CCSS 4.NF.2.

Mathematics 6-8: Algebra tiles for solving equations ($35), probability spinners and dice ($5). Science classes address MS-PS1-1 through particle modeling.

Literacy and Language Arts Strategies

Early readers retell stories using felt characters and settings on bulletin boards, building sight words with magnetic letters. Third through fifth graders create blackout poetry using discarded newspaper articles, physically isolating themes and tone. Sixth through eighth graders freeze into dramatic tableaux of Shakespeare scenes using costume pieces to embody subtext. Tactile story maps using sandpaper for rough settings engage multiple senses during analysis. These experiential education techniques cement comprehension through physical interaction with text, avoiding passive consumption.

Social Studies and Historical Simulations

5th grade: Archaeological dig in sandbox with stratified layers representing different historical periods, using proper tools like brushes and trowels.

8th grade: Mock Constitutional Convention with assigned roles, period-appropriate seating arrangement, and parliamentary procedure.

High school: Stock market simulation with physical currency and ticker tape, or UN Security Council debates with placards and resolution drafting.

Arts and Creative Expression Projects

Elementary students use iStopMotion ($9.99) and clay modeling to animate historical events or book plots, combining digital literacy with tactile creation. Middle schoolers construct found-object sculptures representing geometric shapes or chemical compounds, merging integrative STEM education with artistic vision. High school theater students build set design scale models using foam core and hot glue, calculating proportions and perspective. These project-based learning approaches demonstrate that art studios function as rigorous academic spaces where hands on learning meets aesthetic discipline.

What Are the Most Common Mistakes Teachers Make With Hands-On Learning?

Teachers often mistake hands-on learning for mere entertainment, failing to align activities with specific learning objectives. Common errors include launching complex projects without adequate scaffolding, neglecting safety protocols during science labs, and assessing the product rather than the learning process, resulting in missed educational outcomes.

Busywork disguised as experiential education wastes instructional time. Watch for these red flags before your next project-based learning unit.

Red flag: Students ask "what do I do next?" instead of "what happens if?" Fix: Use backward design starting with the standard.

Red flag: Cleanup takes longer than the learning activity. Fix: Implement the "leave no trace" rule with photo evidence.

Red flag: You spend 30 minutes prepping for 15 minutes of student work. Fix: Simplify materials or switch to digital simulations.

Red flag: Early finishers disrupt others while waiting. Fix: Create extension tasks or cleanup duties.

Confusing Activity With Actual Learning Objectives

When students ask "what do I do next?" instead of "what happens if?", you have recipe-following, not inquiry-based learning. This signals activity-based instruction masquerading as hands on learning.

Apply backward design starting with the standard. If students can complete the task without grasping the concept, redesign it. I watched 4th graders build marshmallow towers once. They had fun. But when I asked about tension versus compression, they stared at me. The manipulatives became toys, not tools. Ensure the activity requires understanding the concept to succeed. Otherwise, you are wasting 30 minutes of prep for 15 minutes of engagement. The "fun over function" trap kills educational value every time.

Insufficient Scaffolding for Complex Tasks

Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development matters here. If students cannot complete the task with minimal guidance, your scaffold is missing. Handing 6th graders electronics kits without teaching series and parallel circuits first creates chaos. They guess. They do not construct. Nothing teaches resignation like impossible tasks.

Use the gradual release model over three lessons. First, "I do" with teacher demonstration. Then "we do" using templates and guided practice. Finally, "you do" allows independent exploration. This prevents frustration while honoring constructivism. Never drop complex kinesthetic activities without foundational skills. Students need the "we do" phase to bridge the gap between watching and doing successfully.

Neglecting Safety and Classroom Management Protocols

Lack of classroom management strategies turns labs into liability nightmares. Require signed safety contracts for chemicals. Mandate eye protection for 5th grade and up. Post material safety data sheets visibly near the supply station. Never skip the safety talk, even for "safe" household items.

Material distribution fails when you hand items to each student. Instead, assign table captains to retrieve supplies from designated stations. For early finishers, post a "before" photo of the clean station. Students cannot line up until their desk matches the image. This "leave no trace" rule prevents cleanup from exceeding learning time. If washing beakers takes longer than the experiment itself, redesign the workflow immediately.

Failure to Connect Activities to Assessment Criteria

Grading the poster's artistic quality while ignoring scientific accuracy misses the point. Separate your rubric into three categories: Scientific Understanding (40%), Procedure Following (30%), and Presentation (30%). This prevents the "fun over function" trap where students build baking soda volcanoes that erupt spectacularly without knowing about chemical reactions or plate tectonics. The eruption becomes mere entertainment, not evidence of learning.

Insert formative checkpoints during long-term project-based learning. Without them, misconceptions solidify and students wander off-task for days. If the product looks great but the student cannot explain the underlying concept, you have craft time, not science class. Assess the learning process through observation and questioning, not just the final display. Check understanding while they work, not only when they finish.

How Do You Assess Student Learning During Hands-On Activities?

Assessment during hands-on learning relies on authentic observation using protocols like the Primary Trait Analysis, student-maintained inquiry notebooks with date-stamped entries, and performance rubrics evaluating both process skills and content mastery. These methods capture learning as it happens without relying solely on post-activity tests.

You cannot grade a lab like a worksheet.

Choose your method based on your goal. Use observation for process skills during kinesthetic activities. Use documentation for inquiry-based learning tracking. Use performance assessment for project-based learning final products.

Watch four or five students deeply each lesson instead of scanning the whole room. Carry a clipboard with time-stamped notes. Rotate through your roster every three to four days. Deep data beats shallow checkmarks.

The thinking is invisible. Capture it by photographing work at ten-minute intervals. Record direct quotes of student speech during manipulatives work. These artifacts show the reasoning behind the final product.

Observation Protocols and Anecdotal Checklists

Use Primary Trait Analysis to stay focused. Pick three specific behaviors—"measures accurately," "controls variables," "makes predictions"—and tally frequency.

Keep a class roster with time-stamped anecdotal notes recording direct quotes of student speech during exploration.

Use your tablet to photograph student work at ten-minute intervals, creating a time-lapse of problem-solving. Keep digital permission slips on file.

I learned this with my 7th graders last spring. I tried watching everyone and missed Marcus misreading the cylinder for fifteen minutes. Now I focus on five students and catch errors early.

Student Documentation and Lab Notebook Methods

Require lab notebooks with date, question, prediction, procedure sketch, data table, and conclusion. Check these daily, not at unit end. The sketch reveals understanding better than paragraphs.

Provide sentence stems for ELL students ("I observed..."). Allow voice-to-text for dysgraphic students or video explanations for reluctant writers. Have students list three safety precautions before starting, initialing each as they follow them during the activity.

Performance-Based Rubrics and Presentations

Design a 4-point rubric: Novice needs constant guidance, Apprentice completes with hints, Proficient succeeds independently, Distinguished extends to new contexts. See our performance-based assessment guide for calibration.

Use "2 stars and 1 wish" for peer review—two compliments and one suggestion using sentence frames. Require a three-minute "science talk" where students defend design choices using evidence. This reveals experiential education and constructivism in action.

What Is the Fastest Way to Start Using Hands-On Learning Tomorrow?

Start hands-on learning tomorrow by selecting one concrete standard suitable for manipulation, gathering found materials like recyclables or nature items, designing a simple three-step protocol with explicit objectives, and preparing management logistics including safety briefings and five-minute reflection time.

You do not need a grant. You need ninety minutes tonight and a garbage bag. Pick one standard, grab some tape and cardboard, and write one sentence describing what students will physically demonstrate. That is your entire plan.

Identify One Standard Suitable for Experiential Learning

Look for verbs that imply doing, not just knowing. Search NGSS for "develop a model" or CCSS Math for "understand" rather than "fluently compute." These indicate standards suitable for experiential education and manipulation.

Kindergarten K-PS2-1 works beautifully—students pushing toy cars to test push and pull forces. Seventh grade 7.RP.A.2 clicks when kids mix paint colors to explore proportional relationships. Biology LS1-2 comes alive with simple egg osmosis experiments.

Avoid standards demanding rote memorization like state capitals or pure computation like multi-digit multiplication algorithms for your first attempt. You want students constructing meaning through constructivism, not just retrieving facts from flashcards.

Gather Low-Cost or Found Materials

Raid your recycling bin first. Paper towel tubes become marble runs. Egg cartons sort manipulatives. Cereal boxes transform into building blocks for towers. Nature provides free supplies for inquiry-based learning: sticks for measurement, leaves for classification, rocks for geology observation.

Dig into your desk drawers. Paper clips create chain reactions. Sticky notes categorize ideas. Rulers and timers collect real data.

Total cost runs zero to five dollars. I once taught a full forces and motion unit to 8th graders using only dried beans as weights, scrap cardboard, and string from the art room. The simplicity actually forced clearer thinking about the physics concepts.

Design a Simple Protocol With Clear Objectives

Map twenty minutes exactly. Two minutes for a hook or discrepant event. Ten minutes for exploration with a "must test three variations" requirement. Five minutes for share-out using your document camera. Three minutes for an exit ticket.

Write the learning target on the board: "I can demonstrate how [concept] works by [action]." Keep it visible throughout this kinesthetic activity.

List three safety rules on the board before you start: materials stay on the tray, voice level two, stop when the signal sounds. Have students repeat them back. Use our lesson plan template and setup guide to structure this protocol without overthinking.

Plan for Management, Safety, and Reflection

Prep stations the night before. Place all materials in baskets with cleanup supplies—sponges and paper towels included. Nothing kills momentum like hunting for a rag with glue on your fingers.

Create one "extension challenge" card for early finishers. It keeps them testing variables while others catch up, preventing disruption.

Place sticky notes and pencils at each table before students arrive. If reflection tools are not ready, the five-minute closing reflection vanishes when the bell rings. This hands on learning cycle demands that students articulate what their fingers discovered before they leave the room.

Hands On Learning: The 3-Step Kickoff

You have enough theory. You know that experiential education sticks better than worksheets, and you have seen how manipulatives turn abstract symbols into something a kid can touch. The hard part is starting without rewriting your entire curriculum. That is where teachers get stuck. They picture a complete overhaul and freeze.

Stop aiming for perfect. Pick one lesson for tomorrow. Swap the passage-reading or the lecture notes for an object students can break, build, or sort. Let the content get a little noisy. The learning happens in that noise—not in the silence of a quiet worksheet.

Choose one standard from your next unit.

Find one physical object that represents the core idea.

Write one inquiry-based question to launch the activity.

Set a timer for ten minutes and say nothing while they figure it out.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.