Tactile Learning: A Complete Guide for K-12 Educators

Tactile Learning: A Complete Guide for K-12 Educators

Tactile Learning: A Complete Guide for K-12 Educators

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

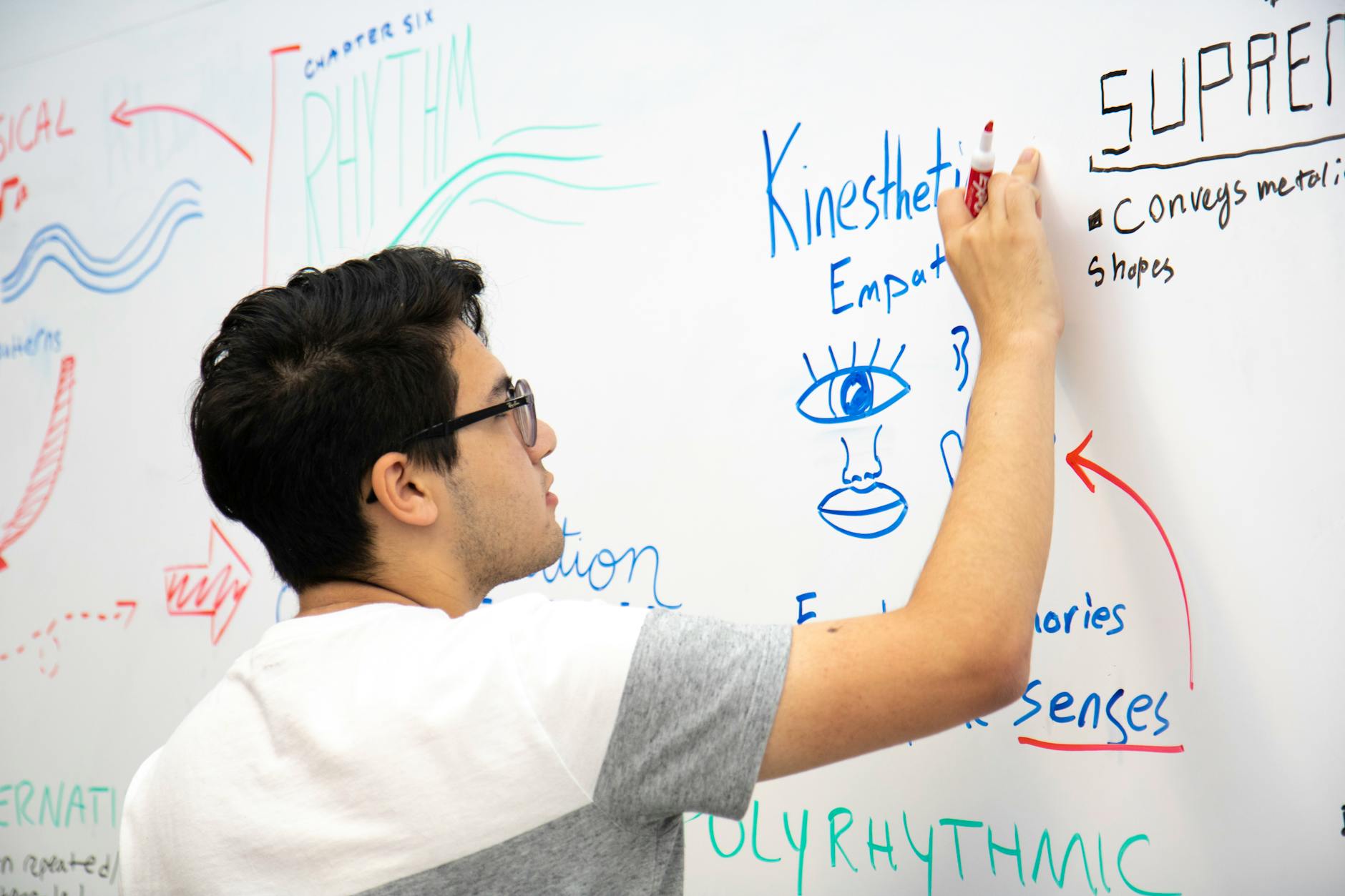

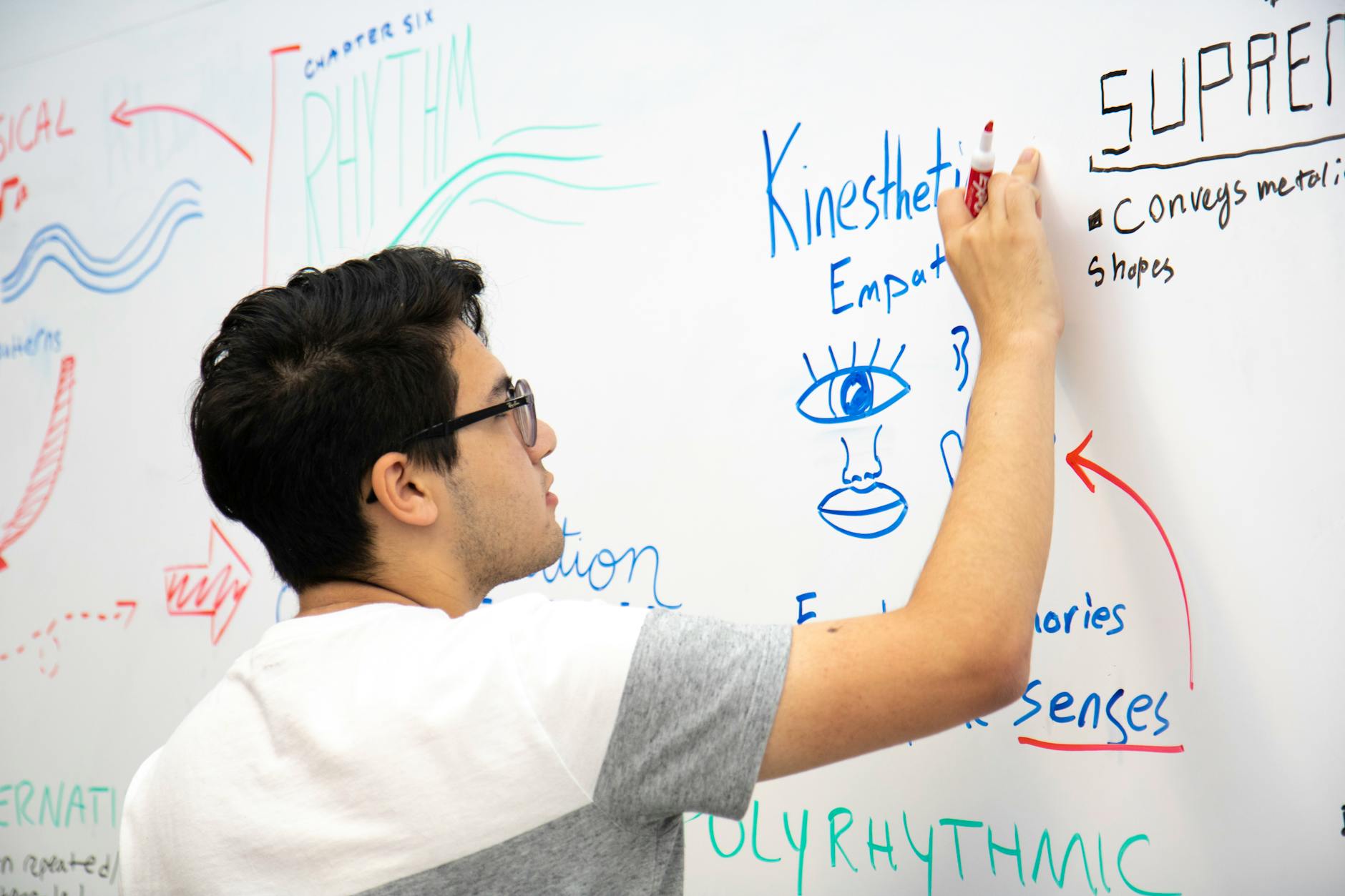

You’ve got that student. The one who taps the desk until the pencils rattle, who needs to pick apart the eraser during your read-aloud, who finally understood fractions only when you let him tear paper into strips. You’re looking for something more than “let them fidget.” You want to know how physical touch actually builds understanding. That’s tactile learning—teaching that puts materials in kids’ hands so their fingers do the thinking before their mouths do the explaining.

It’s not just for early elementary. Your eighth graders still need to feel the weight of density blocks to get buoyancy. Your juniors tracing DNA models with their fingertips retain sequences better than those staring at flat diagrams. When students manipulate objects, their somatosensory cortex fires, creating memory anchors that lectures alone can’t build. Yet most of our classrooms are still designed for eyes and ears only. Worksheets. Slides. Sit-and-get.

This guide cuts through the theory. You’ll learn how touch works in the brain, how to spot the kids who need it most, and specific strategies—manipulatives, embodied cognition tasks, and concrete-representational-abstract sequences—you can use tomorrow without clearing out your supply budget.

You’ve got that student. The one who taps the desk until the pencils rattle, who needs to pick apart the eraser during your read-aloud, who finally understood fractions only when you let him tear paper into strips. You’re looking for something more than “let them fidget.” You want to know how physical touch actually builds understanding. That’s tactile learning—teaching that puts materials in kids’ hands so their fingers do the thinking before their mouths do the explaining.

It’s not just for early elementary. Your eighth graders still need to feel the weight of density blocks to get buoyancy. Your juniors tracing DNA models with their fingertips retain sequences better than those staring at flat diagrams. When students manipulate objects, their somatosensory cortex fires, creating memory anchors that lectures alone can’t build. Yet most of our classrooms are still designed for eyes and ears only. Worksheets. Slides. Sit-and-get.

This guide cuts through the theory. You’ll learn how touch works in the brain, how to spot the kids who need it most, and specific strategies—manipulatives, embodied cognition tasks, and concrete-representational-abstract sequences—you can use tomorrow without clearing out your supply budget.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

What Is Tactile Learning?

Tactile learning—sometimes called haptic learning—is the process of acquiring knowledge through touch and physical manipulation of objects. Unlike passive listening or reading, it engages mechanoreceptors in the skin to send signals to the somatosensory cortex, creating stronger memory traces. In classrooms, this includes activities like tracing letters in sand, building with base-ten blocks, or handling 3D models to understand abstract concepts. While teachers often lump kinesthetic and tactile learners together, the distinction matters when you're choosing between a hands-on lab and a movement break.

Edgar Dale's Cone of Experience gives us the numbers that back this up. Learners retain roughly 10% of what they read but 75% of what they practice by doing. That jump from passive intake to active manipulation explains why your students remember the water cycle better after building a clay model than after reading a diagram. It's not preference—it's physiology.

You can spot a tactile learning style in your classroom through specific behaviors:

Students who build elaborate structures with pencils or paper clips while listening to instructions.

Learners who insist on handwriting notes even when laptops are available, needing the friction of pen on paper to anchor information.

Kids who manipulate objects—Lego bricks, stress balls, fabric swatches—while thinking through a problem.

Defining Tactile Learning and Its Relationship to Kinesthetic Styles

Think of it as a Venn diagram. All tactile learning falls under the umbrella of kinesthetic learning, but not all kinesthetic activity involves touch. Tactile learning specifically requires hand-object contact—fingers moving through texture, weight, and shape. Kinesthetic learning can mean whole-body movement without that sensory feedback.

A student tracing spelling words in shaving cream is engaged in tactile learning. They're using mechanoreceptors in their fingertips to encode the letter shapes. A student performing a dance about photosynthesis is using kinesthetic learning only—big muscle groups, no haptic feedback. Both fall under embodied cognition, but the tactile learner needs that physical resistance against their skin to make the concept stick.

The Neurological Basis of Touch-Based Information Processing

When a student handles manipulatives, signals fire immediately. Touch receptors called mechanoreceptors in the fingertips send electrical impulses through the spinal cord to the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. This happens fast—within 20 to 100 milliseconds. The postcentral gyrus lights up, processing texture, pressure, and temperature alongside the academic content.

This creates what researchers call dual coding. The brain stores not just the fact (the math concept) but the context (the rough texture of the foam block, the weight of the base-ten cube). You get episodic memory—where you were when you learned it—and procedural memory—the physical sequence of movements. These multiple pathways strengthen retrieval, which is why evidence-based best practices for learning styles emphasize multisensory instruction and the concrete-representational-abstract sequence.

Why Does Tactile Learning Matter in Modern Classrooms?

Tactile learning increases retention rates significantly compared to passive methods. Research indicates students retain approximately 75% of material learned through practice by doing versus 10% through reading alone. Additionally, tactile strategies improve engagement for neurodivergent learners, providing sensory regulation that reduces off-task behaviors and supports students with ADHD or dyslexia through multi-sensory encoding.

Edgar Dale's Cone of Experience illustrates these retention differences clearly. His research suggests students remember:

Lecture: 5%

Reading: 10%

Demonstration: 30%

Practice by Doing: 75%

Teaching Others: 90%

These percentages aren't rigid guarantees, but they match what you see in your classroom. Kids forget the worksheet. They remember building the bridge with popsicle sticks.

Some educators hesitate after reading about the "learning styles myth." A 2015 Atlantic article correctly debunked the idea that labeling a child a "kinesthetic and tactile learner" means you should only teach them through touch. But here's the distinction: multimodal instruction benefits everyone. You don't need to sort students into sensory categories to justify using manipulatives. Haptic learning strengthens memory encoding for all brains, not just those supposedly wired for it.

Before you clear space for sensory bins, weigh the trade-offs:

Engagement: High. Students stay focused longer when handling objects.

Cost: Variable. Physical materials cost more than digital slides.

Time: Demanding. Setup and cleanup eat minutes.

Classroom Management: Challenging. Materials can become projectiles without clear protocols.

Retention Rates Compared to Visual and Auditory Instruction

Concrete examples beat digital ones. In studies comparing physical fraction tiles to screen-based representations, students using the actual plastic pieces demonstrated approximately 23% better retention of equivalent fractions after four weeks. The embodied cognition involved in rotating and comparing physical pieces creates stronger neural pathways than watching tiles move on a screen. This supports the concrete-representational-abstract sequence you probably already use in math.

Visual and auditory instruction alone lack the feedback loop that physical manipulation provides. When a student hears a lecture about fractions, they process language. When they see a demonstration, they process images. But when they physically break a clay bar into thirds, they feel the weight change, see the pieces separate, and connect action to concept simultaneously. This multisensory overlap explains why tactile learning outperforms single-modality approaches.

Timing matters too. For elementary students, 15 to 20 minutes of continuous manipulation hits the sweet spot. Beyond that, you see diminishing returns. Hands get tired. Attention drifts. Plan your kinesthetic learning strategies in chunks. A fifteen-minute station rotation with algebra tiles works better than a forty-five-minute marathon.

Engagement Benefits for Diverse and Neurodivergent Learners

Tactile anchors provide sensory regulation that increases on-task behavior. For students with ADHD, manipulating objects reduces the need for self-stimulatory behaviors that disrupt class. When a student squeezes a stress ball while listening, or arranges letter tiles during phonics, the sensory input satisfies their nervous system. They don't need to tap pencils or stand up.

Dyslexic students often struggle with phonological processing alone. Adding tactile input creates additional neural routes to reading. The physical act of tracing sandpaper while saying sounds builds motor memory that visual flashcards cannot replicate.

Specific tools support specific needs:

Fidget tools with learning purpose: Items like texture strips on binders or resistance bands on chair legs that serve the lesson, not just distraction.

Sandpaper letters for dyslexic students: Tracing gritty surfaces while saying sounds creates multisensory instruction that links motor memory to phonemic awareness.

Weighted lap pads during tactile stations: Deep pressure input calms the somatosensory cortex while hands stay busy with manipulatives.

These strategies for tactile learners align with specialized teaching methods for physical and neuromuscular needs. Whether you're adapting for a student with cerebral palsy or designing universal access, physical engagement creates entry points. You don't need separate lesson plans. You need flexible materials that respect how bodies learn.

How Tactile Learning Works in the Brain

When a student runs their finger over a raised letter 'b', the signal travels from mechanoreceptors in their fingertips. It moves up the spinal cord, through the thalamus, and into the somatosensory cortex. From there, it reaches the hippocampus for memory consolidation. This is the biological reality of tactile learning—also called haptic learning: touch creates a durable neural trace before conscious thought even begins. Unlike auditory information that evaporates from working memory in roughly 3-4 seconds, haptic memory persists for approximately 30 seconds without rehearsal. That wider window gives students more time to process new information. Even more powerful is embodied cognition—when a child physically rotates a geometric solid, their brain activates the same spatial reasoning networks used for mental rotation. They are scaffolding abstract thinking through physical action without realizing it.

Somatosensory Processing Pathways and Memory Encoding

The journey from fingertip to long-term storage explains why some memories stick while others slide away within minutes. When students trace sandpaper letters, the rough texture creates what neuroscientists call encoding specificity—a context-dependent memory trace that links the physical sensation directly to the visual symbol. For dyslexic students, this multisensory instruction can be the difference between confusing 'b' and 'd' or recognizing them automatically. The tactile input creates multiple retrieval cues, so the memory isn't dependent on visual processing alone. I've seen students who struggled for months with flashcards suddenly retain letter shapes after three sessions with textured alphabets. The grit under their fingers provides a spatial anchor that visual memory alone cannot offer.

This durability comes from biology, not luck. Repeated tactile activities trigger glial cells to produce myelin, the fatty sheath that insulates neural pathways and speeds up signal transmission. Between ages 5-12, this myelination process is particularly aggressive—exactly when elementary teachers introduce the foundational concepts that underpin later academic success. Every time a student sorts manipulatives, builds with blocks, or handles fossils, they're not just learning content. They're upgrading their neural hardware through brain-based teaching principles that capitalize on natural developmental windows. The more myelin wraps around these sensory-motor pathways, the faster and more automatic the retrieval becomes, turning struggled-over facts into instant recall.

From Physical Manipulation to Abstract Concept Formation

The bridge between holding something and understanding something invisible happens through embodied cognition. When a student physically rotates a 3D geometric solid to count its faces, their premotor cortex lights up in the same pattern it would use to mentally rotate that shape later. The physical action trains the brain for abstract spatial reasoning without the student realizing they're being scaffolded. This is why kinesthetic tactile learners often solve complex math problems by miming the manipulation of objects they no longer physically hold. Their brains have mapped the physical experience and can now run the simulation internally. You can see this when students trace shapes in the air during tests—a remnant of the physical training their neural networks underwent weeks earlier.

The Concrete-Representational-Abstract (CRA) sequence formalizes this transition across all subjects. Each stage builds on the previous, creating a chain of understanding that doesn't break when the physical objects disappear.

Concrete: Students handle physical base-ten blocks, trading ten cubes for one rod and feeling the weight exchange that represents place value.

Representational: Students draw the blocks on paper, converting physical objects to symbols while still referencing the tactile memory.

Abstract: Students use written algorithms like "carry the one," anchored by the sensory memory of the physical trade.

I've watched 3rd graders handle actual fossils, sketching the ridge patterns they felt with their thumbs, then weeks later classify those same structures by era using only text descriptions. The tactile memory of the fossil's weight and texture remains accessible long after the specimen returns to the box. It serves as an invisible reference point for abstract classification systems. Without that initial physical handling, the abstract categories remain fragile and easily confused, collapsing under the weight of pure text-based instruction.

Tactile Learning Strategies for Every Subject Area

Not every lesson needs a manipulative. Sometimes you should skip the hands-on stuff entirely. Standardized test prep week is a bad time to introduce new tactile tools—kids need familiarity, not novelty, when pressure is high. During flu season, skip the shared sand trays; norovirus spreads fast through classroom materials. And respect tactile defensiveness. Students with sensory processing disorders may find certain textures painful rather than helpful. Have paper-and-pencil backups ready. When the conditions are right, though, tactile learning locks in concepts through the somatosensory cortex in ways that worksheets cannot touch. The following tactile learning examples work across grade levels as practical kinesthetic teaching strategies.

Mathematics: Base-Ten Blocks, Fraction Tiles, and Geometric Solids

Base-ten blocks run $25–40 per set. Buy one class set for grades K–3 and you will use them for place value, regrouping, and decimal introduction. For fractions in grades 3–5, Cuisenaire rods beat circular pie pieces because they show equivalency through length, not just area. Middle schoolers need algebra tiles for expanding brackets and factoring; the physical act of flipping a negative tile reinforces sign rules better than any mnemonic. High school geometry teachers can share geometric solids ($30–60 for durable sets) across grades 5–12 for volume and surface area labs.

Base-ten blocks ($25–40): Place value and regrouping (K–3)

Cuisenaire rods: Fraction equivalency through length (3–5)

Algebra tiles: Negative numbers and factoring (6–8)

Geometric solids: Volume and surface area (5–12)

Run the Fraction Restaurant with 4th graders. Students use fraction tiles to fill lunch orders: one table wants ½ pizza plus ¼ soda, another needs of a sandwich. They physically build the sum, trade for equivalent tiles, and write the check total. Assess with a three-point rubric: one point for correct physical assembly, one for accurate equation notation, one for explaining the trade. This follows the concrete-representational-abstract sequence—touch first, draw second, calculate last.

Literacy: Sand Tracing, Letter Tiles, and Textured Vocabulary Cards

Early reading is inherently tactile. Montessori sandpaper letters cost $30, or make your own with glitter glue on cardstock for under $5. Fill a cafeteria tray with salt or sand for $15 total—DIY beats expensive sensory kits. Montessori methods that emphasize physical manipulation work because the finger tracing activates motor memory. Magnetic letter tiles ($20 per set) let kids segment phonemes without the fine motor load of writing. For older students, create textured vocabulary cards with puffy paint on index cards; the raised lines anchor spelling patterns for learning activities for kinesthetic learners who struggle with visual memorization.

Sand trays ($15 DIY): Salt or sand in cafeteria trays for letter formation

Magnetic letter tiles ($20): Phoneme segmentation without writing fatigue

Textured vocabulary cards (puffy paint on index cards): Spelling patterns for grades 3+

Use this three-step sequence with 1st graders. First, they trace sand letters while saying the sound aloud—multisensory instruction at its simplest. Next, they build the word with tiles on a magnetic board, physically pushing each phoneme together to blend. Finally, they write the word on paper. The progression moves from hand to eye to paper without skipping the critical encoding step that many phonics programs rush past.

Science: Hands-On Labs, 3D Models, and Tactile Classification Activities

Science lives in the hands. Physical 3D molecular models run $15–50 per kit, but check if your school library has a 3D printer—manipulatives cost $0.50–$2.00 per student in filament. Owl pellet dissection costs $3 per student and teaches food web concepts through touch. Soil texture analysis with actual samples connects haptic learning to real-world geology. For tactile classification activities, have students sort rock samples or leaf specimens by texture alone, using only their fingertips to distinguish sedimentary from igneous or serrated from smooth margins.

Safety comes first. When chemicals or biohazards are present, gloves substitute for bare-hand contact. But you can still maintain embodied cognition with three alternatives:

Texture boards with sealed specimens

Resin-embedded samples

VR haptics for virtual dissection

These keep the somatosensory cortex engaged without the infection risk.

Social Studies: Artifact Handling, Map Building, and Timeline Construction

History is abstract until you touch it. Contact local museums about replica artifact loans—many have Roman coins, pottery shards, or textile samples for classroom use. Build salt-dough maps for $5 in flour and salt per class; sculpting mountain ranges and river valleys beats coloring them on paper. Timeline construction with physical date cards lets students physically walk through centuries, an example of kinesthetic learning that anchors chronology in muscle memory.

Replica artifacts through museum loan programs

Salt-dough map building ($5 per class in flour and salt)

Timeline construction with physical date cards

Last year my 7th graders handled reproduction Roman coins to understand currency systems. They felt the weight, compared denarii to sestertii, then built barter stations where they traded tactile goods without standardized money. The experiential education framework works because the body remembers the texture of history. These kinesthetic learning activities turn economic theory into physical reality.

How to Identify Tactile Learners in Your Classroom?

Tactile learners typically display specific behavioral markers including doodling or fidgeting with objects while concentrating, preferring handwriting over typing, and excelling in laboratory settings while struggling during lectures. They often remember physical locations of information rather than page numbers. Differentiate from ADHD by observing whether the student seeks texture specifically or general movement.

Behavioral Markers of Tactile Preference

Watch for students who rip paper edges while thinking or fold corners during discussions. These aren't nervous habits—they're haptic learning in action. You'll notice them choose clay modeling over drawing when given the option, or trace text with their finger while reading silently. Their notebooks often show heavy embossing from pressing hard with pens, a sign their somatosensory cortex is engaged.

For a formal check, use a modified VARK inventory with these tactile-specific questions: Do you remember better when you write things by hand? Do you fiddle with objects while thinking hard? Do you prefer building models to reading about them? Do you notice textures of fabrics and surfaces? Do you gesture when explaining ideas? Three or more "yes" answers suggest strong learning types kinesthetic preferences.

Look for these classroom behaviors:

Ripping paper edges rhythmically while listening to instructions

Choosing clay or modeling dough over markers when both are available

Remembering that a fact appeared "at the bottom left of the page" rather than citing page numbers

Tracing lines of text with a finger or pen cap while reading

Creating origami from scrap paper during whole-group discussions

Learn to spot the difference between constructive manipulation and destructive behavior. Green flags include focused fidgeting that accompanies attention—rolling a paperclip, smoothing page corners, or building small structures while listening. The student stays on task; the hands just need occupation. Red flags involve tearing, breaking, or shredding materials due to anxiety or frustration. The first aids embodied cognition; the second signals distress requiring different tactile learner strategies.

Differentiating Tactile Needs From ADHD and General Restlessness

ADHD students seek whole-body movement—they need to pace, bounce, or shift positions constantly. Tactile learners keep their bodies still but their hands busy. Use this decision tree: If removing the fidget object stops the student's work flow, they likely need tactile input to activate their somatosensory cortex for focus. If they continue moving, tapping feet, or shifting regardless of what's in their hands, you're looking at general restlessness or attention differences.

Watch for tactile defensiveness, which mimics disinterest but is actually sensory overload. Signs include recoiling from glue during art projects, refusing to touch sand in the sensory table, or wearing gloves indoors in October. These students need strategies for students with learning disabilities that respect their sensory boundaries while still building tolerance through gradual exposure.

Don't confuse a kinesthetic study style with pathology. Normal tactile learning involves seeking texture for focus; tactile defensiveness involves avoiding touch for comfort. One requires additional manipulatives and multisensory instruction; the other requires space and alternative materials. Getting this wrong means either forcing touch on an overwhelmed child or denying concrete-representational-abstract supports to a student who needs them.

Implementing Tactile Activities Without Losing Control

You can run tactile learning stations without the room devolving into chaos. Implementing these kinesthetic strategies requires spatial logic and hard boundaries. Map your effective classroom design and learning zones before you hand out the first bag of beans.

Setting Up Tactile Stations for Minimal Transition Chaos

Separate wet stations (paint, water, clay) from dry zones (beans, tiles, cards). Arrange traffic clockwise to eliminate collisions. Cap each station at four to six students. Any more and the manipulatives become projectiles. Think of your room as a kitchen: you wouldn't frost cupcakes next to the sink full of dirty brushes.

Pre-count materials into pencil boxes so nobody wastes ten minutes counting out thirty linking cubes.

Post a laminated cleanup checklist at eye level—pictures for younger grades, words for older ones.

Set the visual timer for eight to ten minutes per rotation. When students see the red slice shrinking, they self-regulate better than any teacher voice can manage.

Transitions fail when signals are ambiguous. Give a thirty-second warning, then flash the specific hand signal: hold up the manipulative you're using. When you countdown from five, everyone freezes and stashes materials. No exceptions. Practice this twice on day one until the somatosensory cortex hooks the routine to muscle memory.

Material Management Systems for Efficient Setup and Cleanup

Color-code your bins by subject. Blue for math concrete-representational-abstract kits, green for science measurement tools. Never mix high-mess and low-mess supplies in the same bin—glitter and graph paper should live on opposite sides of the room. Add photo labels to every bin so students know exactly where the protractors belong versus the pipe cleaners.

Assign a "materials manager" job that rotates weekly; that student distributes and collects while you teach.

Set a two-minute timer for cleanup, but add a five-minute buffer before the bell. Table groups race to reset their zone.

The winning team picks the next brain break. It cuts transition time by half.

For tracking classroom materials and inventory, tape QR codes to each bin. When the glue sticks run low or the algebra tiles scatter, scan the code to auto-populate a Google Sheet. You will know exactly what to reorder before Friday dismissal rather than discovering the shortage Monday morning.

Adapting Tactile Methods for Secondary Grade Levels

Secondary teachers face brutal constraints: forty-five-minute periods, thirty-plus students, and 150+ bodies tramping through daily. Storage fits in a milk crate. You cannot run six wet stations with full embodied cognition labs every day.

Institute "Tactile Tuesdays." One day a week, students cycle through haptic learning stations while the rest of the week uses traditional methods.

Use digital manipulatives for Chromebooks: Desmos for math, PhET simulations with trackpad drawing for physics.

Deploy mini-manipulatives in individual gallon bags—one per student. They stash the bag in their backpack or a shoebox under the desk.

This schedule satisfies the multisensory instruction requirement without destroying your pacing guide. When physical space fails, the digital options provide embodied cognition through screen interaction. For kinesthetic study strategies that must be physical, the individual bags keep materials personal and accountable. You keep your sanity and your kinesthetic learning targets while managing the river of adolescents flowing through your door.

Final Thoughts on Tactile Learning

You don't need a cart full of manipulatives or a Pinterest-worthy sensory bin to make this work. The teachers who see real results start small. They pick one worksheet from tomorrow's plan and ask: What could a student touch here? Sometimes the answer is a handful of pennies for math. Sometimes it's a real leaf for science. The shift isn't about cluttering your room with stuff; it's about trusting that embodied cognition works whether the object is fancy or just a rock from the playground.

Your concrete action for today: Before you leave, grab three objects from your desk or supply closet that relate to next week's lesson. Put them in a basket. When the time comes, set the basket on a table and let kids explore before you teach. You'll spot your tactile learners immediately—they'll be the ones who can't stop rolling the objects in their palms while they listen. Start with that single basket. Build your multisensory instruction from there.

What Is Tactile Learning?

Tactile learning—sometimes called haptic learning—is the process of acquiring knowledge through touch and physical manipulation of objects. Unlike passive listening or reading, it engages mechanoreceptors in the skin to send signals to the somatosensory cortex, creating stronger memory traces. In classrooms, this includes activities like tracing letters in sand, building with base-ten blocks, or handling 3D models to understand abstract concepts. While teachers often lump kinesthetic and tactile learners together, the distinction matters when you're choosing between a hands-on lab and a movement break.

Edgar Dale's Cone of Experience gives us the numbers that back this up. Learners retain roughly 10% of what they read but 75% of what they practice by doing. That jump from passive intake to active manipulation explains why your students remember the water cycle better after building a clay model than after reading a diagram. It's not preference—it's physiology.

You can spot a tactile learning style in your classroom through specific behaviors:

Students who build elaborate structures with pencils or paper clips while listening to instructions.

Learners who insist on handwriting notes even when laptops are available, needing the friction of pen on paper to anchor information.

Kids who manipulate objects—Lego bricks, stress balls, fabric swatches—while thinking through a problem.

Defining Tactile Learning and Its Relationship to Kinesthetic Styles

Think of it as a Venn diagram. All tactile learning falls under the umbrella of kinesthetic learning, but not all kinesthetic activity involves touch. Tactile learning specifically requires hand-object contact—fingers moving through texture, weight, and shape. Kinesthetic learning can mean whole-body movement without that sensory feedback.

A student tracing spelling words in shaving cream is engaged in tactile learning. They're using mechanoreceptors in their fingertips to encode the letter shapes. A student performing a dance about photosynthesis is using kinesthetic learning only—big muscle groups, no haptic feedback. Both fall under embodied cognition, but the tactile learner needs that physical resistance against their skin to make the concept stick.

The Neurological Basis of Touch-Based Information Processing

When a student handles manipulatives, signals fire immediately. Touch receptors called mechanoreceptors in the fingertips send electrical impulses through the spinal cord to the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. This happens fast—within 20 to 100 milliseconds. The postcentral gyrus lights up, processing texture, pressure, and temperature alongside the academic content.

This creates what researchers call dual coding. The brain stores not just the fact (the math concept) but the context (the rough texture of the foam block, the weight of the base-ten cube). You get episodic memory—where you were when you learned it—and procedural memory—the physical sequence of movements. These multiple pathways strengthen retrieval, which is why evidence-based best practices for learning styles emphasize multisensory instruction and the concrete-representational-abstract sequence.

Why Does Tactile Learning Matter in Modern Classrooms?

Tactile learning increases retention rates significantly compared to passive methods. Research indicates students retain approximately 75% of material learned through practice by doing versus 10% through reading alone. Additionally, tactile strategies improve engagement for neurodivergent learners, providing sensory regulation that reduces off-task behaviors and supports students with ADHD or dyslexia through multi-sensory encoding.

Edgar Dale's Cone of Experience illustrates these retention differences clearly. His research suggests students remember:

Lecture: 5%

Reading: 10%

Demonstration: 30%

Practice by Doing: 75%

Teaching Others: 90%

These percentages aren't rigid guarantees, but they match what you see in your classroom. Kids forget the worksheet. They remember building the bridge with popsicle sticks.

Some educators hesitate after reading about the "learning styles myth." A 2015 Atlantic article correctly debunked the idea that labeling a child a "kinesthetic and tactile learner" means you should only teach them through touch. But here's the distinction: multimodal instruction benefits everyone. You don't need to sort students into sensory categories to justify using manipulatives. Haptic learning strengthens memory encoding for all brains, not just those supposedly wired for it.

Before you clear space for sensory bins, weigh the trade-offs:

Engagement: High. Students stay focused longer when handling objects.

Cost: Variable. Physical materials cost more than digital slides.

Time: Demanding. Setup and cleanup eat minutes.

Classroom Management: Challenging. Materials can become projectiles without clear protocols.

Retention Rates Compared to Visual and Auditory Instruction

Concrete examples beat digital ones. In studies comparing physical fraction tiles to screen-based representations, students using the actual plastic pieces demonstrated approximately 23% better retention of equivalent fractions after four weeks. The embodied cognition involved in rotating and comparing physical pieces creates stronger neural pathways than watching tiles move on a screen. This supports the concrete-representational-abstract sequence you probably already use in math.

Visual and auditory instruction alone lack the feedback loop that physical manipulation provides. When a student hears a lecture about fractions, they process language. When they see a demonstration, they process images. But when they physically break a clay bar into thirds, they feel the weight change, see the pieces separate, and connect action to concept simultaneously. This multisensory overlap explains why tactile learning outperforms single-modality approaches.

Timing matters too. For elementary students, 15 to 20 minutes of continuous manipulation hits the sweet spot. Beyond that, you see diminishing returns. Hands get tired. Attention drifts. Plan your kinesthetic learning strategies in chunks. A fifteen-minute station rotation with algebra tiles works better than a forty-five-minute marathon.

Engagement Benefits for Diverse and Neurodivergent Learners

Tactile anchors provide sensory regulation that increases on-task behavior. For students with ADHD, manipulating objects reduces the need for self-stimulatory behaviors that disrupt class. When a student squeezes a stress ball while listening, or arranges letter tiles during phonics, the sensory input satisfies their nervous system. They don't need to tap pencils or stand up.

Dyslexic students often struggle with phonological processing alone. Adding tactile input creates additional neural routes to reading. The physical act of tracing sandpaper while saying sounds builds motor memory that visual flashcards cannot replicate.

Specific tools support specific needs:

Fidget tools with learning purpose: Items like texture strips on binders or resistance bands on chair legs that serve the lesson, not just distraction.

Sandpaper letters for dyslexic students: Tracing gritty surfaces while saying sounds creates multisensory instruction that links motor memory to phonemic awareness.

Weighted lap pads during tactile stations: Deep pressure input calms the somatosensory cortex while hands stay busy with manipulatives.

These strategies for tactile learners align with specialized teaching methods for physical and neuromuscular needs. Whether you're adapting for a student with cerebral palsy or designing universal access, physical engagement creates entry points. You don't need separate lesson plans. You need flexible materials that respect how bodies learn.

How Tactile Learning Works in the Brain

When a student runs their finger over a raised letter 'b', the signal travels from mechanoreceptors in their fingertips. It moves up the spinal cord, through the thalamus, and into the somatosensory cortex. From there, it reaches the hippocampus for memory consolidation. This is the biological reality of tactile learning—also called haptic learning: touch creates a durable neural trace before conscious thought even begins. Unlike auditory information that evaporates from working memory in roughly 3-4 seconds, haptic memory persists for approximately 30 seconds without rehearsal. That wider window gives students more time to process new information. Even more powerful is embodied cognition—when a child physically rotates a geometric solid, their brain activates the same spatial reasoning networks used for mental rotation. They are scaffolding abstract thinking through physical action without realizing it.

Somatosensory Processing Pathways and Memory Encoding

The journey from fingertip to long-term storage explains why some memories stick while others slide away within minutes. When students trace sandpaper letters, the rough texture creates what neuroscientists call encoding specificity—a context-dependent memory trace that links the physical sensation directly to the visual symbol. For dyslexic students, this multisensory instruction can be the difference between confusing 'b' and 'd' or recognizing them automatically. The tactile input creates multiple retrieval cues, so the memory isn't dependent on visual processing alone. I've seen students who struggled for months with flashcards suddenly retain letter shapes after three sessions with textured alphabets. The grit under their fingers provides a spatial anchor that visual memory alone cannot offer.

This durability comes from biology, not luck. Repeated tactile activities trigger glial cells to produce myelin, the fatty sheath that insulates neural pathways and speeds up signal transmission. Between ages 5-12, this myelination process is particularly aggressive—exactly when elementary teachers introduce the foundational concepts that underpin later academic success. Every time a student sorts manipulatives, builds with blocks, or handles fossils, they're not just learning content. They're upgrading their neural hardware through brain-based teaching principles that capitalize on natural developmental windows. The more myelin wraps around these sensory-motor pathways, the faster and more automatic the retrieval becomes, turning struggled-over facts into instant recall.

From Physical Manipulation to Abstract Concept Formation

The bridge between holding something and understanding something invisible happens through embodied cognition. When a student physically rotates a 3D geometric solid to count its faces, their premotor cortex lights up in the same pattern it would use to mentally rotate that shape later. The physical action trains the brain for abstract spatial reasoning without the student realizing they're being scaffolded. This is why kinesthetic tactile learners often solve complex math problems by miming the manipulation of objects they no longer physically hold. Their brains have mapped the physical experience and can now run the simulation internally. You can see this when students trace shapes in the air during tests—a remnant of the physical training their neural networks underwent weeks earlier.

The Concrete-Representational-Abstract (CRA) sequence formalizes this transition across all subjects. Each stage builds on the previous, creating a chain of understanding that doesn't break when the physical objects disappear.

Concrete: Students handle physical base-ten blocks, trading ten cubes for one rod and feeling the weight exchange that represents place value.

Representational: Students draw the blocks on paper, converting physical objects to symbols while still referencing the tactile memory.

Abstract: Students use written algorithms like "carry the one," anchored by the sensory memory of the physical trade.

I've watched 3rd graders handle actual fossils, sketching the ridge patterns they felt with their thumbs, then weeks later classify those same structures by era using only text descriptions. The tactile memory of the fossil's weight and texture remains accessible long after the specimen returns to the box. It serves as an invisible reference point for abstract classification systems. Without that initial physical handling, the abstract categories remain fragile and easily confused, collapsing under the weight of pure text-based instruction.

Tactile Learning Strategies for Every Subject Area

Not every lesson needs a manipulative. Sometimes you should skip the hands-on stuff entirely. Standardized test prep week is a bad time to introduce new tactile tools—kids need familiarity, not novelty, when pressure is high. During flu season, skip the shared sand trays; norovirus spreads fast through classroom materials. And respect tactile defensiveness. Students with sensory processing disorders may find certain textures painful rather than helpful. Have paper-and-pencil backups ready. When the conditions are right, though, tactile learning locks in concepts through the somatosensory cortex in ways that worksheets cannot touch. The following tactile learning examples work across grade levels as practical kinesthetic teaching strategies.

Mathematics: Base-Ten Blocks, Fraction Tiles, and Geometric Solids

Base-ten blocks run $25–40 per set. Buy one class set for grades K–3 and you will use them for place value, regrouping, and decimal introduction. For fractions in grades 3–5, Cuisenaire rods beat circular pie pieces because they show equivalency through length, not just area. Middle schoolers need algebra tiles for expanding brackets and factoring; the physical act of flipping a negative tile reinforces sign rules better than any mnemonic. High school geometry teachers can share geometric solids ($30–60 for durable sets) across grades 5–12 for volume and surface area labs.

Base-ten blocks ($25–40): Place value and regrouping (K–3)

Cuisenaire rods: Fraction equivalency through length (3–5)

Algebra tiles: Negative numbers and factoring (6–8)

Geometric solids: Volume and surface area (5–12)

Run the Fraction Restaurant with 4th graders. Students use fraction tiles to fill lunch orders: one table wants ½ pizza plus ¼ soda, another needs of a sandwich. They physically build the sum, trade for equivalent tiles, and write the check total. Assess with a three-point rubric: one point for correct physical assembly, one for accurate equation notation, one for explaining the trade. This follows the concrete-representational-abstract sequence—touch first, draw second, calculate last.

Literacy: Sand Tracing, Letter Tiles, and Textured Vocabulary Cards

Early reading is inherently tactile. Montessori sandpaper letters cost $30, or make your own with glitter glue on cardstock for under $5. Fill a cafeteria tray with salt or sand for $15 total—DIY beats expensive sensory kits. Montessori methods that emphasize physical manipulation work because the finger tracing activates motor memory. Magnetic letter tiles ($20 per set) let kids segment phonemes without the fine motor load of writing. For older students, create textured vocabulary cards with puffy paint on index cards; the raised lines anchor spelling patterns for learning activities for kinesthetic learners who struggle with visual memorization.

Sand trays ($15 DIY): Salt or sand in cafeteria trays for letter formation

Magnetic letter tiles ($20): Phoneme segmentation without writing fatigue

Textured vocabulary cards (puffy paint on index cards): Spelling patterns for grades 3+

Use this three-step sequence with 1st graders. First, they trace sand letters while saying the sound aloud—multisensory instruction at its simplest. Next, they build the word with tiles on a magnetic board, physically pushing each phoneme together to blend. Finally, they write the word on paper. The progression moves from hand to eye to paper without skipping the critical encoding step that many phonics programs rush past.

Science: Hands-On Labs, 3D Models, and Tactile Classification Activities

Science lives in the hands. Physical 3D molecular models run $15–50 per kit, but check if your school library has a 3D printer—manipulatives cost $0.50–$2.00 per student in filament. Owl pellet dissection costs $3 per student and teaches food web concepts through touch. Soil texture analysis with actual samples connects haptic learning to real-world geology. For tactile classification activities, have students sort rock samples or leaf specimens by texture alone, using only their fingertips to distinguish sedimentary from igneous or serrated from smooth margins.

Safety comes first. When chemicals or biohazards are present, gloves substitute for bare-hand contact. But you can still maintain embodied cognition with three alternatives:

Texture boards with sealed specimens

Resin-embedded samples

VR haptics for virtual dissection

These keep the somatosensory cortex engaged without the infection risk.

Social Studies: Artifact Handling, Map Building, and Timeline Construction

History is abstract until you touch it. Contact local museums about replica artifact loans—many have Roman coins, pottery shards, or textile samples for classroom use. Build salt-dough maps for $5 in flour and salt per class; sculpting mountain ranges and river valleys beats coloring them on paper. Timeline construction with physical date cards lets students physically walk through centuries, an example of kinesthetic learning that anchors chronology in muscle memory.

Replica artifacts through museum loan programs

Salt-dough map building ($5 per class in flour and salt)

Timeline construction with physical date cards

Last year my 7th graders handled reproduction Roman coins to understand currency systems. They felt the weight, compared denarii to sestertii, then built barter stations where they traded tactile goods without standardized money. The experiential education framework works because the body remembers the texture of history. These kinesthetic learning activities turn economic theory into physical reality.

How to Identify Tactile Learners in Your Classroom?

Tactile learners typically display specific behavioral markers including doodling or fidgeting with objects while concentrating, preferring handwriting over typing, and excelling in laboratory settings while struggling during lectures. They often remember physical locations of information rather than page numbers. Differentiate from ADHD by observing whether the student seeks texture specifically or general movement.

Behavioral Markers of Tactile Preference

Watch for students who rip paper edges while thinking or fold corners during discussions. These aren't nervous habits—they're haptic learning in action. You'll notice them choose clay modeling over drawing when given the option, or trace text with their finger while reading silently. Their notebooks often show heavy embossing from pressing hard with pens, a sign their somatosensory cortex is engaged.

For a formal check, use a modified VARK inventory with these tactile-specific questions: Do you remember better when you write things by hand? Do you fiddle with objects while thinking hard? Do you prefer building models to reading about them? Do you notice textures of fabrics and surfaces? Do you gesture when explaining ideas? Three or more "yes" answers suggest strong learning types kinesthetic preferences.

Look for these classroom behaviors:

Ripping paper edges rhythmically while listening to instructions

Choosing clay or modeling dough over markers when both are available

Remembering that a fact appeared "at the bottom left of the page" rather than citing page numbers

Tracing lines of text with a finger or pen cap while reading

Creating origami from scrap paper during whole-group discussions

Learn to spot the difference between constructive manipulation and destructive behavior. Green flags include focused fidgeting that accompanies attention—rolling a paperclip, smoothing page corners, or building small structures while listening. The student stays on task; the hands just need occupation. Red flags involve tearing, breaking, or shredding materials due to anxiety or frustration. The first aids embodied cognition; the second signals distress requiring different tactile learner strategies.

Differentiating Tactile Needs From ADHD and General Restlessness

ADHD students seek whole-body movement—they need to pace, bounce, or shift positions constantly. Tactile learners keep their bodies still but their hands busy. Use this decision tree: If removing the fidget object stops the student's work flow, they likely need tactile input to activate their somatosensory cortex for focus. If they continue moving, tapping feet, or shifting regardless of what's in their hands, you're looking at general restlessness or attention differences.

Watch for tactile defensiveness, which mimics disinterest but is actually sensory overload. Signs include recoiling from glue during art projects, refusing to touch sand in the sensory table, or wearing gloves indoors in October. These students need strategies for students with learning disabilities that respect their sensory boundaries while still building tolerance through gradual exposure.

Don't confuse a kinesthetic study style with pathology. Normal tactile learning involves seeking texture for focus; tactile defensiveness involves avoiding touch for comfort. One requires additional manipulatives and multisensory instruction; the other requires space and alternative materials. Getting this wrong means either forcing touch on an overwhelmed child or denying concrete-representational-abstract supports to a student who needs them.

Implementing Tactile Activities Without Losing Control

You can run tactile learning stations without the room devolving into chaos. Implementing these kinesthetic strategies requires spatial logic and hard boundaries. Map your effective classroom design and learning zones before you hand out the first bag of beans.

Setting Up Tactile Stations for Minimal Transition Chaos

Separate wet stations (paint, water, clay) from dry zones (beans, tiles, cards). Arrange traffic clockwise to eliminate collisions. Cap each station at four to six students. Any more and the manipulatives become projectiles. Think of your room as a kitchen: you wouldn't frost cupcakes next to the sink full of dirty brushes.

Pre-count materials into pencil boxes so nobody wastes ten minutes counting out thirty linking cubes.

Post a laminated cleanup checklist at eye level—pictures for younger grades, words for older ones.

Set the visual timer for eight to ten minutes per rotation. When students see the red slice shrinking, they self-regulate better than any teacher voice can manage.

Transitions fail when signals are ambiguous. Give a thirty-second warning, then flash the specific hand signal: hold up the manipulative you're using. When you countdown from five, everyone freezes and stashes materials. No exceptions. Practice this twice on day one until the somatosensory cortex hooks the routine to muscle memory.

Material Management Systems for Efficient Setup and Cleanup

Color-code your bins by subject. Blue for math concrete-representational-abstract kits, green for science measurement tools. Never mix high-mess and low-mess supplies in the same bin—glitter and graph paper should live on opposite sides of the room. Add photo labels to every bin so students know exactly where the protractors belong versus the pipe cleaners.

Assign a "materials manager" job that rotates weekly; that student distributes and collects while you teach.

Set a two-minute timer for cleanup, but add a five-minute buffer before the bell. Table groups race to reset their zone.

The winning team picks the next brain break. It cuts transition time by half.

For tracking classroom materials and inventory, tape QR codes to each bin. When the glue sticks run low or the algebra tiles scatter, scan the code to auto-populate a Google Sheet. You will know exactly what to reorder before Friday dismissal rather than discovering the shortage Monday morning.

Adapting Tactile Methods for Secondary Grade Levels

Secondary teachers face brutal constraints: forty-five-minute periods, thirty-plus students, and 150+ bodies tramping through daily. Storage fits in a milk crate. You cannot run six wet stations with full embodied cognition labs every day.

Institute "Tactile Tuesdays." One day a week, students cycle through haptic learning stations while the rest of the week uses traditional methods.

Use digital manipulatives for Chromebooks: Desmos for math, PhET simulations with trackpad drawing for physics.

Deploy mini-manipulatives in individual gallon bags—one per student. They stash the bag in their backpack or a shoebox under the desk.

This schedule satisfies the multisensory instruction requirement without destroying your pacing guide. When physical space fails, the digital options provide embodied cognition through screen interaction. For kinesthetic study strategies that must be physical, the individual bags keep materials personal and accountable. You keep your sanity and your kinesthetic learning targets while managing the river of adolescents flowing through your door.

Final Thoughts on Tactile Learning

You don't need a cart full of manipulatives or a Pinterest-worthy sensory bin to make this work. The teachers who see real results start small. They pick one worksheet from tomorrow's plan and ask: What could a student touch here? Sometimes the answer is a handful of pennies for math. Sometimes it's a real leaf for science. The shift isn't about cluttering your room with stuff; it's about trusting that embodied cognition works whether the object is fancy or just a rock from the playground.

Your concrete action for today: Before you leave, grab three objects from your desk or supply closet that relate to next week's lesson. Put them in a basket. When the time comes, set the basket on a table and let kids explore before you teach. You'll spot your tactile learners immediately—they'll be the ones who can't stop rolling the objects in their palms while they listen. Start with that single basket. Build your multisensory instruction from there.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.