Socratic Methods of Teaching: A 4-Step Classroom Guide

Socratic Methods of Teaching: A 4-Step Classroom Guide

Socratic Methods of Teaching: A 4-Step Classroom Guide

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

I watched a 10th grader change his mind last Tuesday. He walked into my room dead-set that Romeo was a victim, but twenty minutes of peer questioning later, he admitted the tragedy was self-inflicted—without me saying a word. That shift from certainty to doubt to deeper understanding is exactly what socratic methods of teaching deliver when you stop lecturing and start structuring inquiry. The technique is old, but the classroom application is concrete.

This isn't about playing philosopher on a stool. It's a repeatable system you can build into any subject, any grade level. Below, I break down four specific moves: establishing your core questioning framework, designing the physical and cultural environment for dialogue, facilitating without dominating the conversation, and assessing whether students are actually thinking—or just agreeing with the loudest voice. Each step includes what I wish I'd known before trying this with 7th graders.

I watched a 10th grader change his mind last Tuesday. He walked into my room dead-set that Romeo was a victim, but twenty minutes of peer questioning later, he admitted the tragedy was self-inflicted—without me saying a word. That shift from certainty to doubt to deeper understanding is exactly what socratic methods of teaching deliver when you stop lecturing and start structuring inquiry. The technique is old, but the classroom application is concrete.

This isn't about playing philosopher on a stool. It's a repeatable system you can build into any subject, any grade level. Below, I break down four specific moves: establishing your core questioning framework, designing the physical and cultural environment for dialogue, facilitating without dominating the conversation, and assessing whether students are actually thinking—or just agreeing with the loudest voice. Each step includes what I wish I'd known before trying this with 7th graders.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

What Do You Need Before Implementing Socratic Methods?

Before implementing socratic methods of teaching, you need three fundamentals: a shift from lecturer to facilitator reducing teacher talk to 30%, curriculum content with genuine ambiguity rated 3-4 on the Controversy Continuum, and established intellectual safety norms. Classes should have 12-25 students for optimal dialogue, not 28-plus.

Jumping straight into Socratic seminars without preparation crashes and burns. You need to rewire your instincts from answer-giver to question-asker, audit your curriculum for debatable content, and build trust protocols before touching the complex texts.

Understanding the Teacher's Role Shift

Most of us were trained in Freire's Banking Model—we deposit facts into empty accounts. Socratic teaching method demands the Maieutic Model. You become an intellectual midwife, drawing ideas out, not stuffing them in.

Stop these behaviors immediately:

Confirming answers quickly. Let the ambiguity breathe.

Lecturing for more than five minutes straight.

Playing sage on the stage.

Start asking "What makes you say that?" Then stay silent. Track your talk time with a stopwatch or Equity Maps.

Week one: Aim for 50/50 teacher-student talk.

Week three: Target 70/30 student-to-teacher ratio.

When I first tried understanding the teacher's role shift, I taped a "WAIT" sign to my laptop. It reminded me to pause five seconds after every student comment.

Selecting Appropriate Content for Inquiry

Not everything belongs in a Socratic circle. Use the Controversy Continuum: rate topics 1 through 5. Select only 3s and 4s—issues with evidence on multiple sides. Skip level 1 (multiplication tables) and level 5 (ungrounded opinions).

Apply the Text Selection Rubric:

Ambiguity index: Multiple valid interpretations must exist.

Length: 800-1200 words for high schoolers.

Connection: Clear ties to your essential questions.

Red-flag content includes procedural math, grammar drills, or pure factual recall. When selecting appropriate content for inquiry, I once tried running a seminar on comma rules. It died in eight minutes. Save the dialectical reasoning for questions that actually have multiple valid answers.

The elenchus method only works when students can find contradictory evidence in the text. If the answer is in the first paragraph, pick a different article.

Preparing Your Classroom Culture

Build your culture before touching complex texts. Research by Hattie shows classroom discussion has an effect size of 0.82, placing it in the zone of desired effects. But that requires three hours of upfront preparation and two to three weeks of norm-setting.

Install an Intellectual Safety Charter with five norms:

No personal attacks. Address ideas, not individuals.

Confidentiality: What is said in the circle stays there.

Right to pass. No one forced to speak.

Active listening. No side conversations.

Collective airtime responsibility. Step up, step back.

Practice with icebreaker Socratic questions like "Is pineapple on pizza acceptable?" to rehearse Step Up/Step Back protocols. Dominant speakers must limit themselves to two comments before yielding. Use the Oops/Ouch protocol for accidental offense. Do not attempt this with classes larger than 28 students during testing windows. You need 12 to 25 students for manageable facilitation and diverse perspectives.

Step 1 — Establish Your Core Questioning Framework

Identify Your Essential Question

Essential questions anchor your unit for two to three weeks of inquiry-based learning. Guiding questions probe specific text passages during Tuesday's forty-five minute block. Mix them up and you end up with scattered discussions that never dig deep into dialectical reasoning.

Essential questions demand sustained critical thinking across multiple sources. Guiding questions check for basic comprehension of a single page. If you ask "What year did World War II end?" you have a guiding question. If you ask "Was the New Deal a success for all Americans?" you have an essential question that spans economic, social, and racial dimensions.

Run every candidate through four rigorous filters before committing to it for three weeks. First, eliminate any question with a single correct answer that shuts down debate. Second, demand textual evidence to support any claim students make. Third, connect the question to a transferable concept that shows up in other units and disciplines. Fourth, ensure the question provokes genuine disagreement among your students avoiding easy consensus.

For ninth-grade history, "Was the New Deal a success for all Americans?" passes all four filters with room to spare. Some students will cite job creation statistics and infrastructure projects. Others will point to racial exclusions in relief programs or the persistence of unemployment among specific demographics that the data masks.

Test your question with the one-word answer rule before you print it on the board. If you can answer with "yes," "no," or a single fact, revise it immediately. A valid essential question requires at least 150 words to answer with nuance and qualification. If your students can settle it in a single sentence, you have guiding question material, not an inquiry anchor for socratic questioning in education.

Map Conceptual Predecessors and Extensions

Backwards design saves you from those blank stares that kill momentum mid-seminar. Start with your essential question at the top of a large concept map on chart paper. Branch down to three prerequisite understandings students must master first before they can argue intelligently. Branch up to two extension questions for advanced learners who finish early.

Before debating "Did Macbeth have free will?" ensure students grasp Elizabethan fate beliefs, the Great Chain of Being, and the difference between tragic flaw and external manipulation. These three concepts form the foundation. Without them, students will emote about the plot and miss the philosophical tension.

For extensions, ask: "How do modern psychological theories of addiction reinterpret Macbeth's choices?" and "Does fate function differently in Oedipus Rex than in Macbeth?" These push your advanced students toward comparative literature and higher order thinking skills while others catch up.

Anticipate three specific misconceptions that derail teaching critical thinking strategies in your content area. Students often think Romeo and Juliet died from bad luck rather than impulsive choice. They confuse correlation with causation when analyzing historical trends. They assume authors always agree with their narrators.

Prepare specific questions to surface these errors avoiding embarrassment for the student. "Some people think the lovers were just unlucky—what do you think?" invites revision better than calling out the mistake. "Did the economy improve because of the policy or despite it?" addresses causation confusion directly. These prepared redirects keep the Paideia seminar moving through productive elenchus method.

Prepare Follow-Up and Redirection Strategies

Master the five Socratic moves that drive intellectual midwifery in your classroom. These form the backbone of your Redirection Arsenal when discussions stall.

Clarification asks "What do you mean by X?"

Assumption probes demand "What are you assuming about human nature?"

Evidence requests insist on "What data supports that claim?"

Viewpoint shifts wonder "How would a critic respond to your position?"

Implication tracing follows with "What follows from that if we apply it to other cases?"

Type ten question stems on a cue card you keep in your palm during seminars. Include "Can you give an example?" for clarification. Add "What would change your mind?" for evidence testing. Write "Is that always true or just here?" to challenge assumptions. Keep "Who benefits from that interpretation?" for viewpoint shifts. "What are the stakes?" works for implication tracing.

These ten stems form your Redirection Arsenal when discussions drift into anecdote. Print them on brightly colored cardstock so you spot them quickly under your lesson plan. Glance down whenever a student finishes speaking and you feel the silence stretching.

Structure your Follow-Up Funnel to build depth, not breadth. The first student response gets clarification to ensure understanding. The second response gets an evidence request to test foundations. The third response gets implication tracing to explore consequences. Never ask a new question before processing the current answer fully.

This rhythm turns socratic methods of teaching into genuine inquiry, not guessing games. Students learn that you will not bail them out with easier questions when the thinking gets hard. They adjust their initial responses, refine their claims, and engage in true intellectual midwifery through disciplined elenchus method.

Step 2 — Design the Physical and Cultural Environment

Arrange Seating for Eye Contact and Equity

You have three solid layouts to choose from for your Paideia seminar:

Fishbowl: 8 to 10 students in the inner circle, 16 to 20 observers outside. Keep the inner diameter under 8 feet for voice projection.

Horseshoe: U-shape with 24 inches between chairs. Gap the ends no wider than 12 inches to prevent isolation.

Boardroom: Four hexagonal tables of six for 24 total, ideal for small-group synthesis feeding into whole-class discussion.

Arrange seating for eye contact and equity by checking sightlines from every seat. All students must sit within 15 feet of the text display. If a student cannot see without turning her head, move her immediately.

Track participation with conversation maps. Students draw lines connecting speakers. If anyone has fewer than two lines after 15 minutes, intervene with a direct question. This visual feedback makes patterns visible to everyone, including the quiet students themselves.

Establish Intellectual Safety Norms

Post these four norms where everyone can see them:

Address ideas, not individuals.

Use the stem "I disagree because..." before challenging any claim.

Offer a pass option, but follow it with "What would you guess?"

No hand raising; you control traffic flow while students read the room for natural pauses.

This foundation enables dialectical reasoning to flourish. Students need to know that intellectual midwifery requires risk-taking, and you are protecting that risk.

Hang a "Disagreement Sentence Frames" poster with phrases like "I see it differently because...", "I understand your point about X, but consider...", and "The evidence seems to suggest...". These starters slow reactivity and support English learners who need linguistic scaffolding.

Introduce the Pause Protocol. Any student may call "Pause" if feeling unsafe. Everyone writes privately for two minutes. This prevents shutdown while maintaining momentum. Resume with a narrower question that feels manageable. Practice this protocol once before using it for real.

Select and Prepare Source Material or Prompts

Socratic methods of teaching require texts with interpretive wiggle room, not single-answer worksheets that shut down thinking. Consider these source types:

Ambiguous short stories under five pages for middle school.

Primary sources with internal contradictions for high school, such as Jefferson's writings on equality versus his slaveholding.

Data sets showing correlation without causation for math and science inquiries.

Prepare layered texts. Offer the same content at three reading levels. Federalist Paper #10 might appear in original language, a summarized version, and a graphic organizer. Everyone tackles the same essential question regardless of reading speed. This ensures inquiry-based learning remains inclusive and accessible.

Create a Text-to-Question Anchor. Display your essential question visibly on chart paper. Mark three to four hotspots in the text where the question intersects with specific passages. This keeps discussion grounded in evidence, not mere opinion. Point to the anchor when the conversation drifts toward anecdote.

Step 3 — Facilitate Dialogue Without Dominating

Launch your socratic methods of teaching with the essential question you scripted during planning. Then enforce Rowe's Wait Time protocol: five seconds minimum for recall questions, ten for synthesis. I use a visible countdown timer projected on the board because my instinct to break silence hits at 2.3 seconds, and students know it.

Buffer participation with Think-Pair-Share. Ninety seconds of individual writing first. Two minutes of partner talk second. Whole group last. This sequence pushes participation from the usual 30% of extroverts to 80% of your class, including the quiet kid in the back who actually read the chapter.

Track dialectical reasoning by tallying student-to-student links on your clipboard. Aim for 60% of comments referencing peers ("Building on Sarah's point..."). Use only three stems to drive effective class participation methods: "Say more," "Who disagrees?" and "Where's your evidence?"

Avoid three facilitation failures that kill inquiry-based learning:

Reasking the question when a student blanks. Redirect to another student.

Summarizing the discussion yourself. Ask "How would you summarize what you heard?"

Accepting "I don't know" without the "If you had to guess, based on the text?" follow-up.

Every pause builds critical thinking. Your silence is the soil where student ideas grow.

Open with Your Prepared Question

Ask your opening question exactly once. If you get silence, do not rephrase. Do not simplify. Wait the full ten seconds, then use the "Phone a Friend" move: call a specific student by name. "Jordan, what's your instinct here?" This maintains the cognitive demand while breaking the ice.

Prohibit teacher validation during the opening ten minutes. No "Good point," no "Exactly," no nodding approval. Students fish for your reaction instead of engaging in intellectual midwifery. I learned this the hard way when my 11th graders kept looking at me instead of each other during a Paideia seminar on Macbeth. Once I went stone-faced, they started arguing about ambition without checking my expression for the "right" answer.

The question should sit on the board, visible to everyone. Point to it. Wait. Do not touch it with your voice again until the discussion shifts to new territory.

Apply Strategic Wait Time and Silence

Implement "Wait Time 2": after a student stops talking, count three to five seconds before you respond. Research shows 40% of students will add significant content to their initial thought if you don't jump in. They reread the passage. They correct themselves. The silence does the teaching.

Use physical cues to facilitate dialogue without dominating. Step back from the center of the room. Plant your feet near the wall. Make eye contact with students other than the speaker. Adopt an expectant posture—raised eyebrows, open hands—to signal the floor remains open. You are not the audience. The room is.

When the timer runs out, scan the room. Do not call on the first hand. Wait for a second, then a third. Choose the student who rarely speaks. This rewards patience over speed.

Connect Student Responses Using Socratic Moves

Execute the "Ping-Pong Redirect." When Student A finishes, look directly at Student B and ask, "How does that land with you?" or "Where do you see that in the text?" This enforces the elenchus method—testing ideas through peer response rather than teacher validation. The conversation zigzags between learners, creating a web of socratic questioning in teaching.

Maintain the "No Repeating" rule strictly. If a student says "I didn't hear him," you do not repeat the comment. Ask another student to paraphrase or repeat it. This distributes authority among the class and forces active listening. It also prevents you from becoming the amplifier, which keeps you out of the center and preserves the inquiry-based learning dynamic you're building.

If the conversation stalls, use the "What if" stem. "What if the author had written the opposite?" This restart requires no teacher opinion, only student speculation. Track the dialogue pattern mentally. When three consecutive comments reference the teacher ("Is this right?"), interrupt the chain. Point to two students who haven't spoken: "Maria, respond to David's claim." This restores the peer-to-peer flow.

Step 4 — How Do You Assess Thinking and Refine Your Practice?

Assess Socratic discussions using a rubric weighing reasoning (40%) and evidence use (30%) over correctness. Track student-to-student connection frequency and gather reflections via exit tickets asking what changed their mind. Record sessions to audit your own talk time, aiming for under 20% of total speaking.

Stop grading kids on whether they reached your conclusion. Start measuring how they got there. When you assess process and reasoning over right answers, you shift from intellectual gatekeeper to midwife—helping ideas emerge, not stamping them approved.

Assess Process and Reasoning Over Right Answers

Build a four-point rubric presented as a scoring matrix: Claim Clarity (1-4), Evidence Use (1-4), Reasoning Logic (1-4), and Intellectual Humility (1-4). Weight Reasoning Logic at 40 percent and Evidence Use at 30 percent. Claim Clarity and Intellectual Humility each claim 15 percent. Exclude Correct Answer from the matrix entirely.

Forty-eight hours after the Paideia seminar, deploy the Reasoning Log assessment. Students submit a one-page written argument that must incorporate at least two distinct peer ideas from the discussion and one counterargument they did not originally hold. This captures critical thinking once the adrenaline of debate fades and proves they listened.

Split the final grade to honor process: 50 percent from participation quality using the rubric, 30 percent from the Reasoning Log, and 20 percent from pre-seminar text annotations or question prep. Award zero points for having the "right" interpretation. This structure mirrors the elenchus method—testing beliefs through scrutiny rather than memorization.

Last semester, my 10th graders argued about Antigone's loyalty. The student who changed his mind mid-seminar earned the top score not for flip-flopping, but for mapping the logic that moved him. When you assess process and reasoning over right answers, you honor the socratic methods of teaching that value inquiry over compliance.

Gather Student Reflections on the Experience

Administer a three-question exit ticket before they leave. Ask: What idea changed your mind today? What question remains unanswered? How did you help others think better? Add a Likert scale asking, "I felt safe sharing unpopular views," scored 1 to 5.

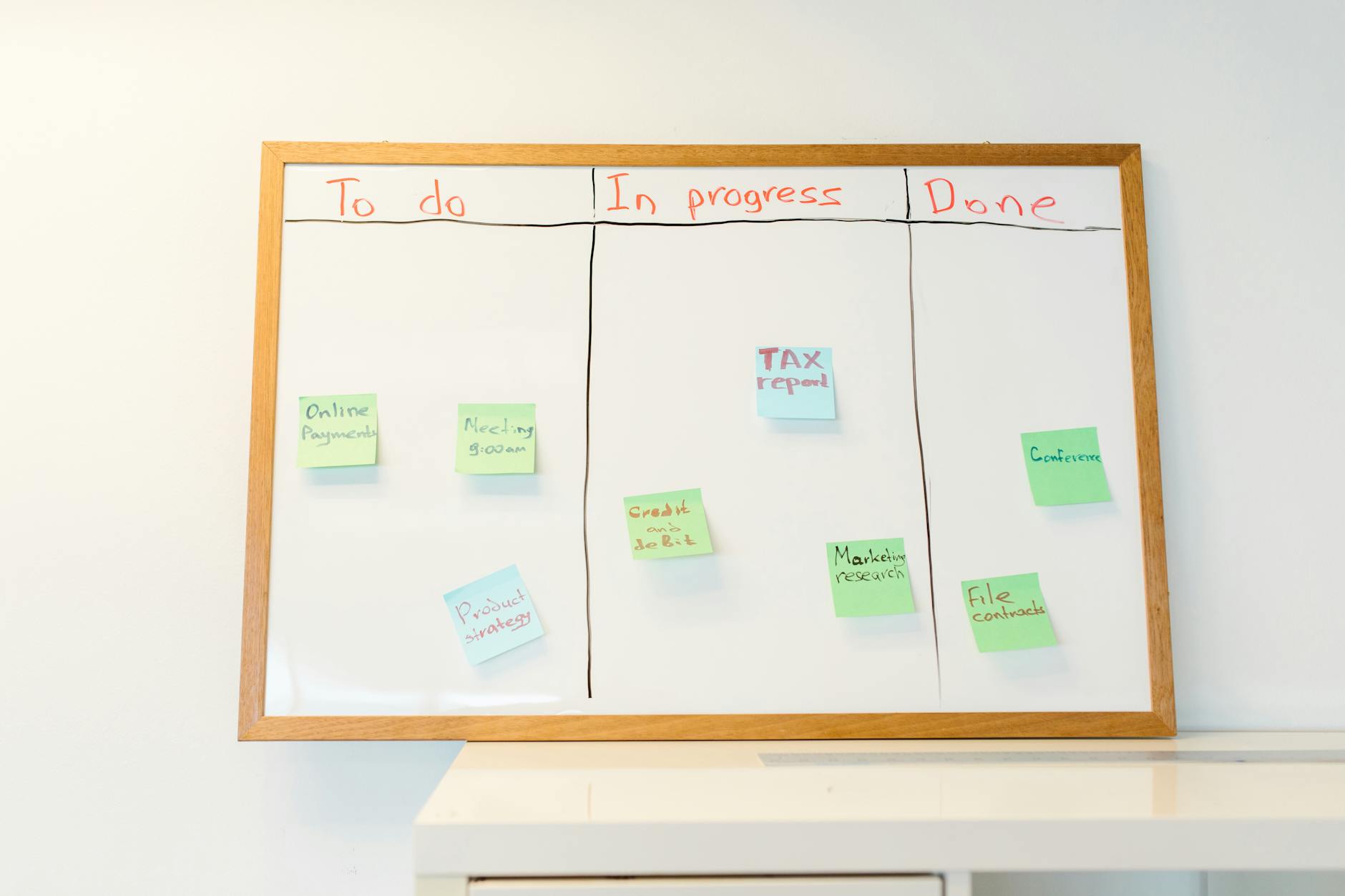

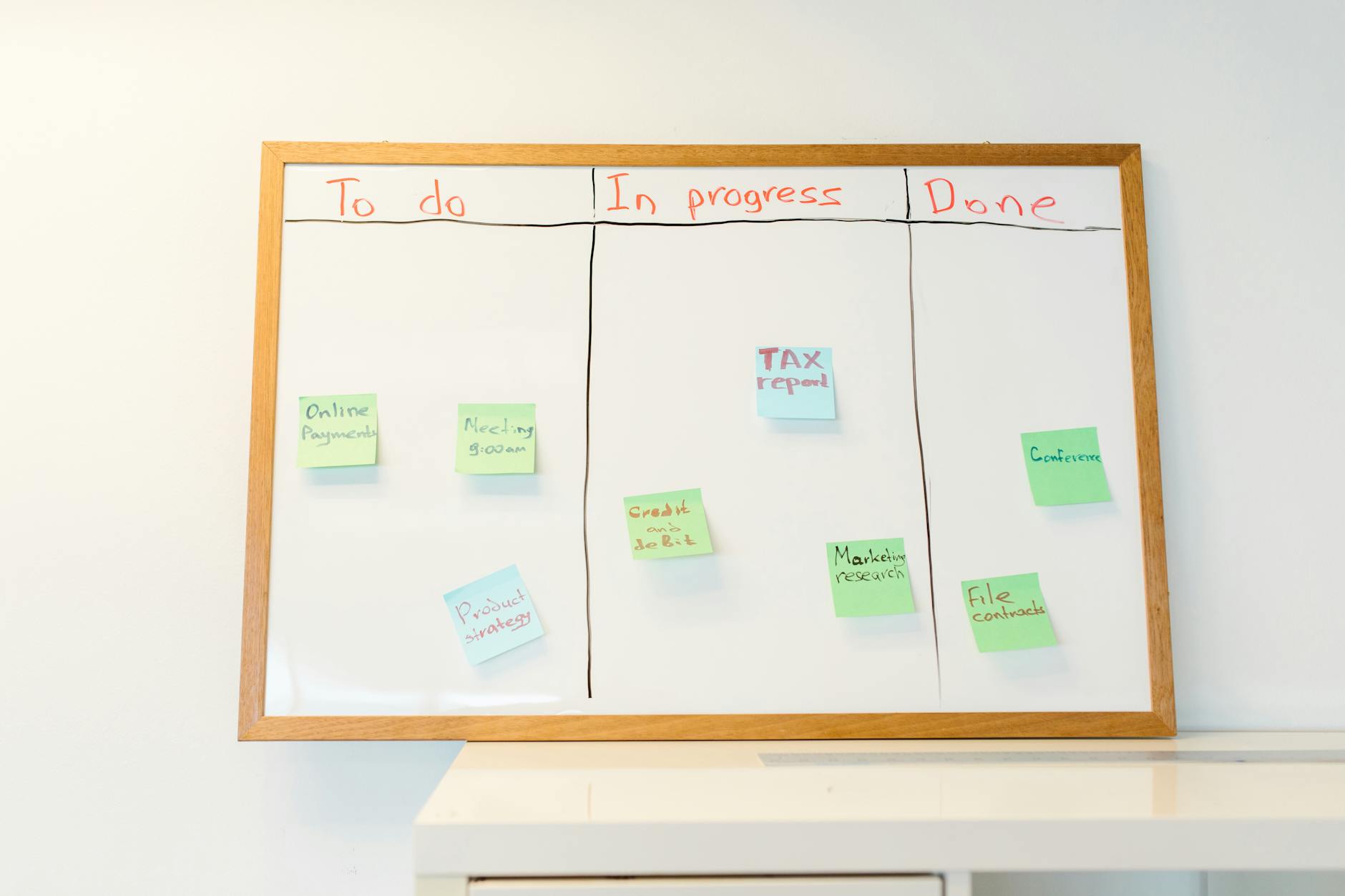

Run the Plus/Delta protocol immediately post-seminar. Students write one thing that worked well (Plus) and one thing to change (Delta) on sticky notes. Cluster these on a board while the next class enters. Patterns emerge in seconds—maybe the inner circle talked too long or the text lacked context.

Have students rate their own contribution 0-10 against specific criteria: I cited specific evidence, I built on others' ideas, I asked clarifying questions. Compare their numbers with your observation data. Last week, my 7th graders' sticky notes revealed the Delta "wait time was too short" clustered heavily on the left side of the board.

When you gather student reflections on the experience, you stop guessing whether the inquiry-based learning actually worked. Their self-assessment scores averaged 6.2 while I marked them at 5.1—useful calibration for my next socratic questioning in the classroom session.

Iterate Your Question Sequence for Next Time

Record every seminar. Use the Session Audit Protocol: calculate your talk time percentage, aiming for under 20 percent of total speaking. Count dead-end questions that generated only yes or no responses. Remap your question sequence to eliminate 2-question stacks—never ask a new question before students process the first.

Print the transcript and grab two highlighters. Mark every teacher question in yellow and every student-to-student link in blue. If yellow exceeds 40 percent of total interventions, you dominated the inquiry. Revise your plan to embrace silence and let dialectical reasoning flow between them, not through you.

Retire questions that elicited unanimous agreement—they taught nothing. Keep and rephrase questions that sparked productive disagreement. For queries that exceeded time limits, draft extension branches: follow-up prompts that push deeper when the clock runs short.

Last month I audited a recording and found I spoke 24 percent of the time—too much. I had stacked questions: "Why did the character choose exile? What would you have done?" Students answered only the second. Now I write one question per index card and force myself to wait. This refines your practice session by session.

One Thing to Try This Week

You do not need to flip your entire classroom overnight. Pick one period tomorrow and try the five-minute pause from Step 3. When a student answers your core question, wait. Count to seven in your head. Let the silence push someone else to build on that thought or ask for clarification. Watch what happens to the quality of dialectical reasoning when you stop filling every gap with your own voice.

This is how inquiry-based learning actually starts. You have the questioning framework from Step 1, the room arrangement from Step 2, and the assessment tools from Step 4. Now test them with one discussion. Note which students spoke who usually stay quiet, and where the Paideia seminar format felt forced. That data becomes your first refinement cycle before you scale up.

Your first move is concrete. Write one open-ended question on a sticky note before class tomorrow. Tape it to your laptop. When the moment comes, ask it, then close your mouth. Count to ten. Let the critical thinking begin.

What Do You Need Before Implementing Socratic Methods?

Before implementing socratic methods of teaching, you need three fundamentals: a shift from lecturer to facilitator reducing teacher talk to 30%, curriculum content with genuine ambiguity rated 3-4 on the Controversy Continuum, and established intellectual safety norms. Classes should have 12-25 students for optimal dialogue, not 28-plus.

Jumping straight into Socratic seminars without preparation crashes and burns. You need to rewire your instincts from answer-giver to question-asker, audit your curriculum for debatable content, and build trust protocols before touching the complex texts.

Understanding the Teacher's Role Shift

Most of us were trained in Freire's Banking Model—we deposit facts into empty accounts. Socratic teaching method demands the Maieutic Model. You become an intellectual midwife, drawing ideas out, not stuffing them in.

Stop these behaviors immediately:

Confirming answers quickly. Let the ambiguity breathe.

Lecturing for more than five minutes straight.

Playing sage on the stage.

Start asking "What makes you say that?" Then stay silent. Track your talk time with a stopwatch or Equity Maps.

Week one: Aim for 50/50 teacher-student talk.

Week three: Target 70/30 student-to-teacher ratio.

When I first tried understanding the teacher's role shift, I taped a "WAIT" sign to my laptop. It reminded me to pause five seconds after every student comment.

Selecting Appropriate Content for Inquiry

Not everything belongs in a Socratic circle. Use the Controversy Continuum: rate topics 1 through 5. Select only 3s and 4s—issues with evidence on multiple sides. Skip level 1 (multiplication tables) and level 5 (ungrounded opinions).

Apply the Text Selection Rubric:

Ambiguity index: Multiple valid interpretations must exist.

Length: 800-1200 words for high schoolers.

Connection: Clear ties to your essential questions.

Red-flag content includes procedural math, grammar drills, or pure factual recall. When selecting appropriate content for inquiry, I once tried running a seminar on comma rules. It died in eight minutes. Save the dialectical reasoning for questions that actually have multiple valid answers.

The elenchus method only works when students can find contradictory evidence in the text. If the answer is in the first paragraph, pick a different article.

Preparing Your Classroom Culture

Build your culture before touching complex texts. Research by Hattie shows classroom discussion has an effect size of 0.82, placing it in the zone of desired effects. But that requires three hours of upfront preparation and two to three weeks of norm-setting.

Install an Intellectual Safety Charter with five norms:

No personal attacks. Address ideas, not individuals.

Confidentiality: What is said in the circle stays there.

Right to pass. No one forced to speak.

Active listening. No side conversations.

Collective airtime responsibility. Step up, step back.

Practice with icebreaker Socratic questions like "Is pineapple on pizza acceptable?" to rehearse Step Up/Step Back protocols. Dominant speakers must limit themselves to two comments before yielding. Use the Oops/Ouch protocol for accidental offense. Do not attempt this with classes larger than 28 students during testing windows. You need 12 to 25 students for manageable facilitation and diverse perspectives.

Step 1 — Establish Your Core Questioning Framework

Identify Your Essential Question

Essential questions anchor your unit for two to three weeks of inquiry-based learning. Guiding questions probe specific text passages during Tuesday's forty-five minute block. Mix them up and you end up with scattered discussions that never dig deep into dialectical reasoning.

Essential questions demand sustained critical thinking across multiple sources. Guiding questions check for basic comprehension of a single page. If you ask "What year did World War II end?" you have a guiding question. If you ask "Was the New Deal a success for all Americans?" you have an essential question that spans economic, social, and racial dimensions.

Run every candidate through four rigorous filters before committing to it for three weeks. First, eliminate any question with a single correct answer that shuts down debate. Second, demand textual evidence to support any claim students make. Third, connect the question to a transferable concept that shows up in other units and disciplines. Fourth, ensure the question provokes genuine disagreement among your students avoiding easy consensus.

For ninth-grade history, "Was the New Deal a success for all Americans?" passes all four filters with room to spare. Some students will cite job creation statistics and infrastructure projects. Others will point to racial exclusions in relief programs or the persistence of unemployment among specific demographics that the data masks.

Test your question with the one-word answer rule before you print it on the board. If you can answer with "yes," "no," or a single fact, revise it immediately. A valid essential question requires at least 150 words to answer with nuance and qualification. If your students can settle it in a single sentence, you have guiding question material, not an inquiry anchor for socratic questioning in education.

Map Conceptual Predecessors and Extensions

Backwards design saves you from those blank stares that kill momentum mid-seminar. Start with your essential question at the top of a large concept map on chart paper. Branch down to three prerequisite understandings students must master first before they can argue intelligently. Branch up to two extension questions for advanced learners who finish early.

Before debating "Did Macbeth have free will?" ensure students grasp Elizabethan fate beliefs, the Great Chain of Being, and the difference between tragic flaw and external manipulation. These three concepts form the foundation. Without them, students will emote about the plot and miss the philosophical tension.

For extensions, ask: "How do modern psychological theories of addiction reinterpret Macbeth's choices?" and "Does fate function differently in Oedipus Rex than in Macbeth?" These push your advanced students toward comparative literature and higher order thinking skills while others catch up.

Anticipate three specific misconceptions that derail teaching critical thinking strategies in your content area. Students often think Romeo and Juliet died from bad luck rather than impulsive choice. They confuse correlation with causation when analyzing historical trends. They assume authors always agree with their narrators.

Prepare specific questions to surface these errors avoiding embarrassment for the student. "Some people think the lovers were just unlucky—what do you think?" invites revision better than calling out the mistake. "Did the economy improve because of the policy or despite it?" addresses causation confusion directly. These prepared redirects keep the Paideia seminar moving through productive elenchus method.

Prepare Follow-Up and Redirection Strategies

Master the five Socratic moves that drive intellectual midwifery in your classroom. These form the backbone of your Redirection Arsenal when discussions stall.

Clarification asks "What do you mean by X?"

Assumption probes demand "What are you assuming about human nature?"

Evidence requests insist on "What data supports that claim?"

Viewpoint shifts wonder "How would a critic respond to your position?"

Implication tracing follows with "What follows from that if we apply it to other cases?"

Type ten question stems on a cue card you keep in your palm during seminars. Include "Can you give an example?" for clarification. Add "What would change your mind?" for evidence testing. Write "Is that always true or just here?" to challenge assumptions. Keep "Who benefits from that interpretation?" for viewpoint shifts. "What are the stakes?" works for implication tracing.

These ten stems form your Redirection Arsenal when discussions drift into anecdote. Print them on brightly colored cardstock so you spot them quickly under your lesson plan. Glance down whenever a student finishes speaking and you feel the silence stretching.

Structure your Follow-Up Funnel to build depth, not breadth. The first student response gets clarification to ensure understanding. The second response gets an evidence request to test foundations. The third response gets implication tracing to explore consequences. Never ask a new question before processing the current answer fully.

This rhythm turns socratic methods of teaching into genuine inquiry, not guessing games. Students learn that you will not bail them out with easier questions when the thinking gets hard. They adjust their initial responses, refine their claims, and engage in true intellectual midwifery through disciplined elenchus method.

Step 2 — Design the Physical and Cultural Environment

Arrange Seating for Eye Contact and Equity

You have three solid layouts to choose from for your Paideia seminar:

Fishbowl: 8 to 10 students in the inner circle, 16 to 20 observers outside. Keep the inner diameter under 8 feet for voice projection.

Horseshoe: U-shape with 24 inches between chairs. Gap the ends no wider than 12 inches to prevent isolation.

Boardroom: Four hexagonal tables of six for 24 total, ideal for small-group synthesis feeding into whole-class discussion.

Arrange seating for eye contact and equity by checking sightlines from every seat. All students must sit within 15 feet of the text display. If a student cannot see without turning her head, move her immediately.

Track participation with conversation maps. Students draw lines connecting speakers. If anyone has fewer than two lines after 15 minutes, intervene with a direct question. This visual feedback makes patterns visible to everyone, including the quiet students themselves.

Establish Intellectual Safety Norms

Post these four norms where everyone can see them:

Address ideas, not individuals.

Use the stem "I disagree because..." before challenging any claim.

Offer a pass option, but follow it with "What would you guess?"

No hand raising; you control traffic flow while students read the room for natural pauses.

This foundation enables dialectical reasoning to flourish. Students need to know that intellectual midwifery requires risk-taking, and you are protecting that risk.

Hang a "Disagreement Sentence Frames" poster with phrases like "I see it differently because...", "I understand your point about X, but consider...", and "The evidence seems to suggest...". These starters slow reactivity and support English learners who need linguistic scaffolding.

Introduce the Pause Protocol. Any student may call "Pause" if feeling unsafe. Everyone writes privately for two minutes. This prevents shutdown while maintaining momentum. Resume with a narrower question that feels manageable. Practice this protocol once before using it for real.

Select and Prepare Source Material or Prompts

Socratic methods of teaching require texts with interpretive wiggle room, not single-answer worksheets that shut down thinking. Consider these source types:

Ambiguous short stories under five pages for middle school.

Primary sources with internal contradictions for high school, such as Jefferson's writings on equality versus his slaveholding.

Data sets showing correlation without causation for math and science inquiries.

Prepare layered texts. Offer the same content at three reading levels. Federalist Paper #10 might appear in original language, a summarized version, and a graphic organizer. Everyone tackles the same essential question regardless of reading speed. This ensures inquiry-based learning remains inclusive and accessible.

Create a Text-to-Question Anchor. Display your essential question visibly on chart paper. Mark three to four hotspots in the text where the question intersects with specific passages. This keeps discussion grounded in evidence, not mere opinion. Point to the anchor when the conversation drifts toward anecdote.

Step 3 — Facilitate Dialogue Without Dominating

Launch your socratic methods of teaching with the essential question you scripted during planning. Then enforce Rowe's Wait Time protocol: five seconds minimum for recall questions, ten for synthesis. I use a visible countdown timer projected on the board because my instinct to break silence hits at 2.3 seconds, and students know it.

Buffer participation with Think-Pair-Share. Ninety seconds of individual writing first. Two minutes of partner talk second. Whole group last. This sequence pushes participation from the usual 30% of extroverts to 80% of your class, including the quiet kid in the back who actually read the chapter.

Track dialectical reasoning by tallying student-to-student links on your clipboard. Aim for 60% of comments referencing peers ("Building on Sarah's point..."). Use only three stems to drive effective class participation methods: "Say more," "Who disagrees?" and "Where's your evidence?"

Avoid three facilitation failures that kill inquiry-based learning:

Reasking the question when a student blanks. Redirect to another student.

Summarizing the discussion yourself. Ask "How would you summarize what you heard?"

Accepting "I don't know" without the "If you had to guess, based on the text?" follow-up.

Every pause builds critical thinking. Your silence is the soil where student ideas grow.

Open with Your Prepared Question

Ask your opening question exactly once. If you get silence, do not rephrase. Do not simplify. Wait the full ten seconds, then use the "Phone a Friend" move: call a specific student by name. "Jordan, what's your instinct here?" This maintains the cognitive demand while breaking the ice.

Prohibit teacher validation during the opening ten minutes. No "Good point," no "Exactly," no nodding approval. Students fish for your reaction instead of engaging in intellectual midwifery. I learned this the hard way when my 11th graders kept looking at me instead of each other during a Paideia seminar on Macbeth. Once I went stone-faced, they started arguing about ambition without checking my expression for the "right" answer.

The question should sit on the board, visible to everyone. Point to it. Wait. Do not touch it with your voice again until the discussion shifts to new territory.

Apply Strategic Wait Time and Silence

Implement "Wait Time 2": after a student stops talking, count three to five seconds before you respond. Research shows 40% of students will add significant content to their initial thought if you don't jump in. They reread the passage. They correct themselves. The silence does the teaching.

Use physical cues to facilitate dialogue without dominating. Step back from the center of the room. Plant your feet near the wall. Make eye contact with students other than the speaker. Adopt an expectant posture—raised eyebrows, open hands—to signal the floor remains open. You are not the audience. The room is.

When the timer runs out, scan the room. Do not call on the first hand. Wait for a second, then a third. Choose the student who rarely speaks. This rewards patience over speed.

Connect Student Responses Using Socratic Moves

Execute the "Ping-Pong Redirect." When Student A finishes, look directly at Student B and ask, "How does that land with you?" or "Where do you see that in the text?" This enforces the elenchus method—testing ideas through peer response rather than teacher validation. The conversation zigzags between learners, creating a web of socratic questioning in teaching.

Maintain the "No Repeating" rule strictly. If a student says "I didn't hear him," you do not repeat the comment. Ask another student to paraphrase or repeat it. This distributes authority among the class and forces active listening. It also prevents you from becoming the amplifier, which keeps you out of the center and preserves the inquiry-based learning dynamic you're building.

If the conversation stalls, use the "What if" stem. "What if the author had written the opposite?" This restart requires no teacher opinion, only student speculation. Track the dialogue pattern mentally. When three consecutive comments reference the teacher ("Is this right?"), interrupt the chain. Point to two students who haven't spoken: "Maria, respond to David's claim." This restores the peer-to-peer flow.

Step 4 — How Do You Assess Thinking and Refine Your Practice?

Assess Socratic discussions using a rubric weighing reasoning (40%) and evidence use (30%) over correctness. Track student-to-student connection frequency and gather reflections via exit tickets asking what changed their mind. Record sessions to audit your own talk time, aiming for under 20% of total speaking.

Stop grading kids on whether they reached your conclusion. Start measuring how they got there. When you assess process and reasoning over right answers, you shift from intellectual gatekeeper to midwife—helping ideas emerge, not stamping them approved.

Assess Process and Reasoning Over Right Answers

Build a four-point rubric presented as a scoring matrix: Claim Clarity (1-4), Evidence Use (1-4), Reasoning Logic (1-4), and Intellectual Humility (1-4). Weight Reasoning Logic at 40 percent and Evidence Use at 30 percent. Claim Clarity and Intellectual Humility each claim 15 percent. Exclude Correct Answer from the matrix entirely.

Forty-eight hours after the Paideia seminar, deploy the Reasoning Log assessment. Students submit a one-page written argument that must incorporate at least two distinct peer ideas from the discussion and one counterargument they did not originally hold. This captures critical thinking once the adrenaline of debate fades and proves they listened.

Split the final grade to honor process: 50 percent from participation quality using the rubric, 30 percent from the Reasoning Log, and 20 percent from pre-seminar text annotations or question prep. Award zero points for having the "right" interpretation. This structure mirrors the elenchus method—testing beliefs through scrutiny rather than memorization.

Last semester, my 10th graders argued about Antigone's loyalty. The student who changed his mind mid-seminar earned the top score not for flip-flopping, but for mapping the logic that moved him. When you assess process and reasoning over right answers, you honor the socratic methods of teaching that value inquiry over compliance.

Gather Student Reflections on the Experience

Administer a three-question exit ticket before they leave. Ask: What idea changed your mind today? What question remains unanswered? How did you help others think better? Add a Likert scale asking, "I felt safe sharing unpopular views," scored 1 to 5.

Run the Plus/Delta protocol immediately post-seminar. Students write one thing that worked well (Plus) and one thing to change (Delta) on sticky notes. Cluster these on a board while the next class enters. Patterns emerge in seconds—maybe the inner circle talked too long or the text lacked context.

Have students rate their own contribution 0-10 against specific criteria: I cited specific evidence, I built on others' ideas, I asked clarifying questions. Compare their numbers with your observation data. Last week, my 7th graders' sticky notes revealed the Delta "wait time was too short" clustered heavily on the left side of the board.

When you gather student reflections on the experience, you stop guessing whether the inquiry-based learning actually worked. Their self-assessment scores averaged 6.2 while I marked them at 5.1—useful calibration for my next socratic questioning in the classroom session.

Iterate Your Question Sequence for Next Time

Record every seminar. Use the Session Audit Protocol: calculate your talk time percentage, aiming for under 20 percent of total speaking. Count dead-end questions that generated only yes or no responses. Remap your question sequence to eliminate 2-question stacks—never ask a new question before students process the first.

Print the transcript and grab two highlighters. Mark every teacher question in yellow and every student-to-student link in blue. If yellow exceeds 40 percent of total interventions, you dominated the inquiry. Revise your plan to embrace silence and let dialectical reasoning flow between them, not through you.

Retire questions that elicited unanimous agreement—they taught nothing. Keep and rephrase questions that sparked productive disagreement. For queries that exceeded time limits, draft extension branches: follow-up prompts that push deeper when the clock runs short.

Last month I audited a recording and found I spoke 24 percent of the time—too much. I had stacked questions: "Why did the character choose exile? What would you have done?" Students answered only the second. Now I write one question per index card and force myself to wait. This refines your practice session by session.

One Thing to Try This Week

You do not need to flip your entire classroom overnight. Pick one period tomorrow and try the five-minute pause from Step 3. When a student answers your core question, wait. Count to seven in your head. Let the silence push someone else to build on that thought or ask for clarification. Watch what happens to the quality of dialectical reasoning when you stop filling every gap with your own voice.

This is how inquiry-based learning actually starts. You have the questioning framework from Step 1, the room arrangement from Step 2, and the assessment tools from Step 4. Now test them with one discussion. Note which students spoke who usually stay quiet, and where the Paideia seminar format felt forced. That data becomes your first refinement cycle before you scale up.

Your first move is concrete. Write one open-ended question on a sticky note before class tomorrow. Tape it to your laptop. When the moment comes, ask it, then close your mouth. Count to ten. Let the critical thinking begin.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.