Higher Order Thinking Skills: 5 Steps to Transform Your Teaching

Higher Order Thinking Skills: 5 Steps to Transform Your Teaching

Higher Order Thinking Skills: 5 Steps to Transform Your Teaching

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

Most of what passes for higher order thinking skills in curriculum materials is just recall with extra steps. I've watched 7th graders label a worksheet "analysis" because they circled three adjectives instead of one. Real critical thinking isn't about harder worksheets or longer essays. It's about moving students from consuming information to interrogating it. If your students can answer the question with a Google search, you haven't built thinking skills. You've built search skills.

I spent three years chasing Bloom's taxonomy verbs before I realized the framework doesn't matter if your questions stay at the bottom rung. You can slap "evaluate" on a prompt, but if students just pick between two pre-selected opinions, you're still at low cognitive demand. The shift happens when you audit your own language, pick a framework that fits your subject, and rebuild your questioning from the ground up. When I stopped asking what happened and started asking why it matters, my classroom changed. That's what actually moves kids from memorization to metacognition.

Most of what passes for higher order thinking skills in curriculum materials is just recall with extra steps. I've watched 7th graders label a worksheet "analysis" because they circled three adjectives instead of one. Real critical thinking isn't about harder worksheets or longer essays. It's about moving students from consuming information to interrogating it. If your students can answer the question with a Google search, you haven't built thinking skills. You've built search skills.

I spent three years chasing Bloom's taxonomy verbs before I realized the framework doesn't matter if your questions stay at the bottom rung. You can slap "evaluate" on a prompt, but if students just pick between two pre-selected opinions, you're still at low cognitive demand. The shift happens when you audit your own language, pick a framework that fits your subject, and rebuild your questioning from the ground up. When I stopped asking what happened and started asking why it matters, my classroom changed. That's what actually moves kids from memorization to metacognition.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Understanding the Foundation of Higher Order Thinking

Defining the Six Cognitive Levels

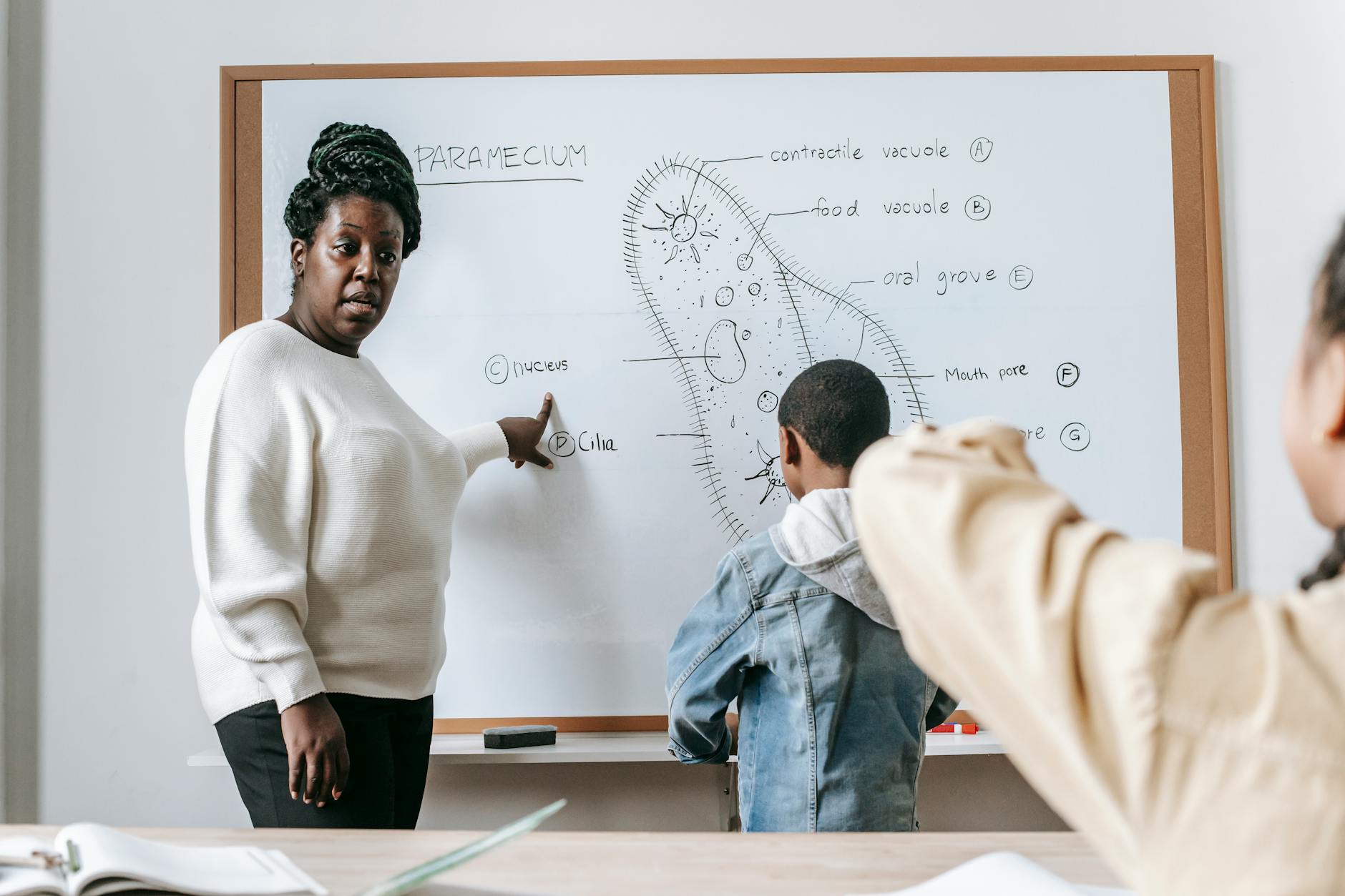

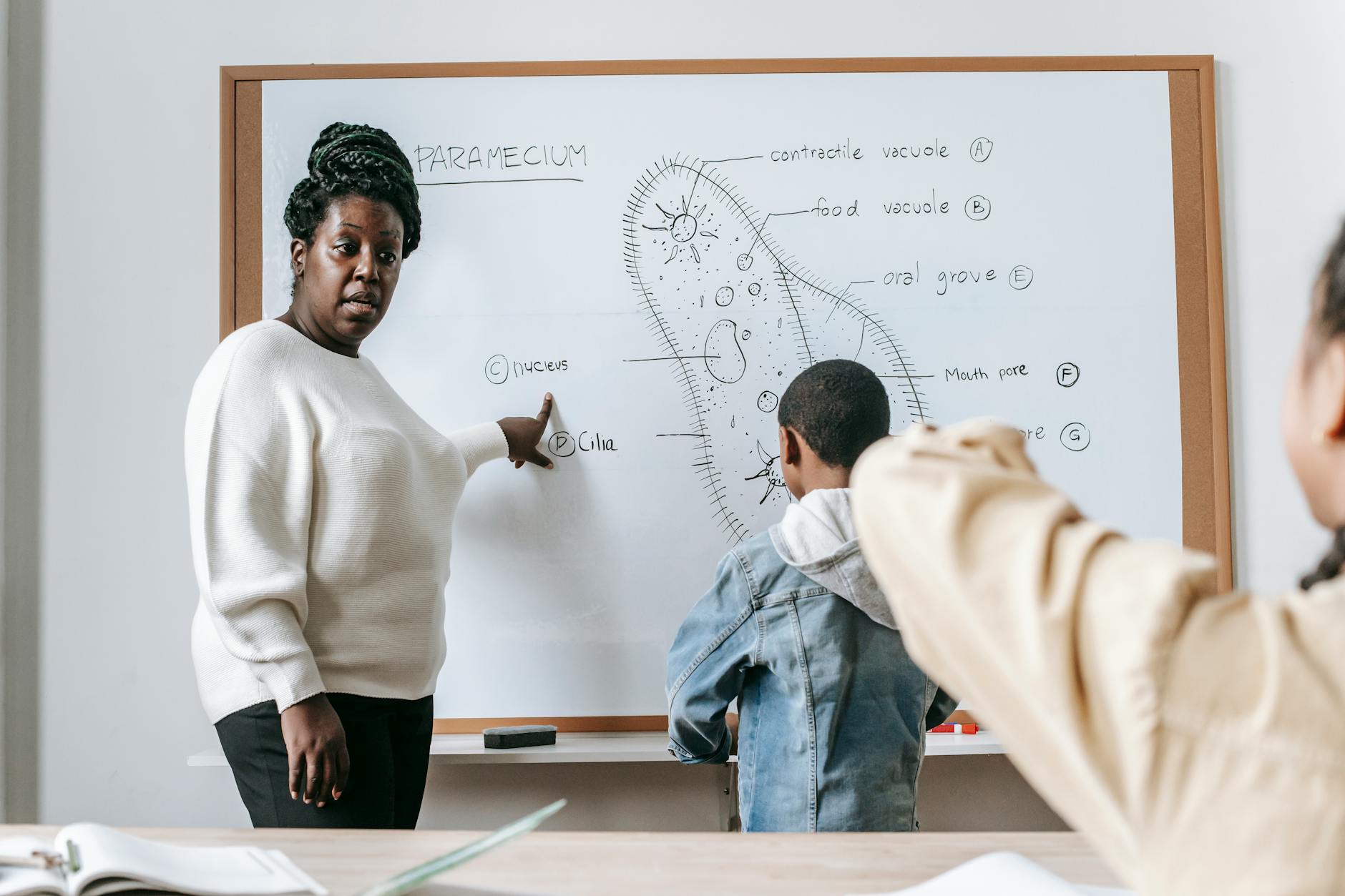

Anderson and Krathwohl's revised Bloom's Taxonomy gives us six rungs to climb. At the bottom, Remember asks students to define or list—like when your fourth graders recite times tables from memory or label parts of a cell diagram. Understand moves to classifying and summarizing, such as explaining the causes of the Civil War in their own words without copying the textbook.

Apply means executing and implementing procedures with precision. Students use the Pythagorean theorem to solve real-world measurement problems they haven't seen before. Analyze requires them to differentiate and organize—comparing mitosis versus meiosis in a detailed Venn diagram or sorting primary sources by reliability and bias. Evaluate demands critique and systematic testing, like assessing whether a historical account holds up when cross-checked with artifacts and other documents.

At the top, Create involves designing and constructing original work from scratch. Your eighth graders compose argumentative essays with cited evidence defending a nuanced claim, or design osmosis experiments testing original variables they selected independently. This is where cognitive levels and development strategies shift from consuming knowledge to building new understanding. These thinking skills separate simple recall from the critical thinking we actually want students to own.

The Difference Between Difficult and Complex Tasks

Harder is not the same as complex. A difficult task loads working memory with extra steps but follows a known algorithm you have practiced. Calculating fifty compound interest problems taxes stamina yet requires only one formula applied repeatedly. Five-digit long division works the same way every single time. These tasks challenge concentration without demanding independent judgment.

Complex tasks present competing variables and no single pathway forward. Designing a school recycling program with strict budget limits and space constraints forces students to prioritize conflicting criteria. Determining which investment strategy optimizes growth requires balancing inflation rates, risk tolerance, and liquidity needs simultaneously. The student must develop new criteria rather than follow old ones.

Use this decision matrix: if the work requires following a memorized procedure, you have cognitive demand but not higher order thinking skills. If it requires students to invent the procedure, weigh trade-offs, and justify their reasoning with evidence, you have true complexity. Difficult tasks consume mental energy; complex tasks build metacognition and visible thinking that transfers.

Prerequisites for Student Readiness

Before you push for analysis, check the foundation. Students need roughly eighty percent accuracy on level two Understand tasks before they can handle level four Analyze work in your classroom. Research indicates experts hold over fifty thousand domain-specific knowledge chunks; novices need time to build that schema. John Hattie's meta-analyses show prior achievement carries an effect size of 0.60 for predicting success with complex tasks.

Administer a diagnostic with ten items spanning levels one through four. Students ready for thinking based learning answer eight out of ten level two items correctly and can verbalize their problem-solving process without prompting or hinting. Working memory must juggle three to four variables simultaneously without crashing under the load.

Look for three specific behaviors during your observation. The student explains reasoning using "because" statements that connect evidence to claims. They spot logical errors in worked examples you display on the board. They transfer the skill to a novel context with seventy percent accuracy or better. Miss these markers and your Webb's Depth of Knowledge level four lesson will crash against working memory limits.

Step 1 — Audit Your Current Questioning Patterns

Map Your Existing Questions Against Bloom's Taxonomy

Record one 45-minute lesson on your phone. Transcribe every question you ask. You will likely find 25 to 40 questions in a typical class period. Code each one using Bloom's Taxonomy verb lists. Calculate your current ratio of Remember/Understand questions versus Analyze/Evaluate/Create prompts. Most teachers hover around 70 percent low-level questioning. Aim to flip that to 60 percent higher-order by semester's end.

Use a color-highlighting system. Mark levels 1-2 in pink, levels 3-4 in yellow, and levels 5-6 in green. Tally the frequencies. You can use the TAG (Taxonomy Assessment Grid) or a simple spreadsheet with dropdown menus for rapid coding. I prefer Google Sheets with conditional formatting that turns cells pink automatically when I type "Remember." Here is the tracking template:

Question Text | Bloom Level (1-6) | Student Response Word Count | Wait Time (seconds) | Follow-up Strategy Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

What is the main idea? | 1 | 3 | 2 | None |

How would you test this hypothesis? | 5 | 45 | 8 | Probing for evidence |

Analyze Student Response Patterns

If 80 percent of student responses are single words or phrases, your questioning is likely stuck at levels 1-2. When students generate novel questions or use disciplinary vocabulary spontaneously, you have reached level 4 or above. This visible thinking signals that your thinking strategies are working.

Track the average word count per response. For higher order thinking skills to develop, target 15 or more words per answer. Count how often students ask each other questions instead of funneling everything through you. Note when they request clarification or demand evidence from peers. These metacognition markers reveal true cognitive demand.

Review your audio recording at double speed. Mark the timestamp each time a student speaks uninterrupted for more than 10 seconds. Those long turns indicate higher-order processing is actually happening. Last fall, I discovered my 7th graders spoke in 45-second bursts during argumentation tasks but only 3-second bursts during review games. The data does not lie.

Identify Cognitive Bottlenecks in Your Curriculum

Map your sequence of 10 consecutive lessons. Look for cognitive cliffs where tasks jump from level 2 to level 5 without warning. For example, you might ask students to summarize causes one day and immediately demand they evaluate the most significant cause the next. That gap crushes critical thinking development and leaves students stranded.

Insert bridge activities to close these gaps. Add comparison tasks at level 4 before asking for evaluations at level 5. Let students analyze the relative weight of factors before judging significance. This scaffolding prevents the frustration that shuts down inquiry. For more on building these bridges, explore these teaching critical thinking strategies.

Check your scope and sequence for Webb's Depth of Knowledge alignment. A healthy progression moves students through application and analysis before demanding creation. When you spot a cliff, drop in a visible thinking routine. Graphic organizers for comparing sources work wonders before synthesis essays.

Step 2 — Select a Thinking Framework That Fits Your Subject

Bloom's Taxonomy vs. Webb's Depth of Knowledge

Bloom's Taxonomy sorts thinking by cognitive process. It moves from Remember through Create, focusing on what skill the student uses. Webb's Depth of Knowledge measures cognitive demand—how deeply the content must be processed. Webb offers four levels: Recall, Skills/Concepts, Strategic Thinking, and Extended Thinking. Bloom's Create aligns with Webb's DOK 4, both demanding extended thinking. However, Bloom's Analyze can land at DOK 2 or 3 depending on context. DOK levels 3 and 4 align with higher order thinking skills but emphasize how deeply students must interact with the content rather than which verb they use.

State education departments often publish thinking skills in education pdf guides that map these alignments side-by-side for easy reference. Choose Bloom when building skill sequences and writing lesson objectives. Choose Webb when aligning assessments to NGSS or CCSS standards. STEM subjects benefit from Webb's clarity on mathematical modeling and scientific inquiry. Humanities subjects work better with Bloom for developing rhetorical analysis and argumentation where the intellectual move matters more than the content complexity.

Subject-Specific Modifications

Science teachers should layer NGSS Science and Engineering Practices alongside Bloom. Focus on Developing and Using Models at DOK 3 and Constructing Explanations at DOK 4. These practices make the abstract concrete when students build physical or computational models rather than just memorizing facts about phenomena. For ELA, add the Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework. Its Elements of Thought—purpose, question, information, inference, assumption, and point of view—layer cleanly over Bloom's levels. When students analyze a text, they identify assumptions and implications rather than just listing examples.

This adds rigor to literary essays by forcing students to examine their own critical thinking processes. Art teachers should adopt Studio Thinking from Project Zero. The Eight Habits of Mind include Engage and Persist, Envision, Observe, and Reflect. These visible thinking routines build metacognition while students work through creative problems. Downloadable charts from Project Zero serve as thinking skills in education pdf references you can keep at your planning desk or share with parents during conferences.

Creating a Common Language for Your Classroom

Develop a classroom lexicon that sticks. Choose three thinking strategies per week and weave them into your instructions across subjects. When students hear Evaluate used consistently in math, reading, and science, they recognize critical thinking as a transferable skill rather than a subject-specific trick. Keep the language consistent from September through June. Build a visual word wall with icons. Place a magnifying glass next to Analyze, a balance scale next to Evaluate, and construction tools next to Create. Add sentence starters for each level so students know how to enter the conversation.

Post these at eye level where students can reference them during independent work or peer discussions. Run a five-minute verb warm-up daily. Students use the target thinking verb three times in conversation before you begin the lesson. This primes their brains for higher order thinking skills work. When developing adaptive thinking skills becomes routine, students stop guessing what you want and start knowing how to think through problems systematically rather than hunting for right answers.

Step 3 — How Do You Transform Low-Level Questions Into Higher Order Challenges?

Transform low-level questions by adding conditional scenarios ('how would this change if...'), requiring cross-context comparison, or removing given information. For example, change 'What is the main idea?' to 'How would the main idea shift if the protagonist chose differently?' This forces conditional reasoning and evidence-based speculation rather than simple retrieval.

Three upgrades consistently raise cognitive demand in your classroom. First, append a conditional clause: "How would X change if Y occurred?" Second, force comparison across contexts: "Contrast X with Z situation." Third, strip away given information: "Solve without using the quadratic formula." Each method requires students to manipulate knowledge rather than simply retrieve it.

In your seventh-grade history class, replace "When did the Civil War begin?" with "How would the war's trajectory differ if it had begun in 1850 versus 1861?" The original asks for a date. Your revised version demands critical thinking about economic readiness, political tensions, and military capacity across two distinct timelines.

Converting Recall Questions to Analysis Prompts

Move beyond memorization by injecting causality, perspective shifts, or categorization demands into your questions. Ask "What caused X to lead to Y?" or "How would X appear from an opposing viewpoint?" Alternatively, require sorting: "Which category of economic system does this represent and why?" These shifts immediately activate metacognition as students must justify their classifications. You ensure they cannot answer without processing relationships between disconnected concepts.

Watch this progression in your biology class. Instead of "Name the parts of a cell," ask "Which organelles would be most affected by a toxin blocking protein synthesis and why?" Your students still need to know the organelles, but now they must apply that knowledge to a novel scenario. This hits Bloom's taxonomy analysis level and mirrors authentic scientific reasoning rather than flashcard recall.

Adding Constraints to Spark Creative Evaluation

Limit resources to force creative evaluation in your assessments. Impose a fifty-dollar budget, a twenty-four-hour deadline, or ethical boundaries like "solution cannot displace existing residents." Material limits work too: "Build this using only paper and tape." These constraints mirror authentic engineering problems and elevate visible thinking as students navigate trade-offs. When you remove their default tools, you force innovation and prioritize what truly matters.

Replace the generic prompt "Evaluate this argument" with "Evaluate this argument using only evidence from primary sources dated before 1950, considering the author's economic status." Suddenly your students cannot rely on generalizations or hindsight. They must weigh historical context against available data, a core component of hots teaching strategies that builds historical empathy and rigorous source literacy simultaneously.

Designing Questions With Multiple Valid Pathways

Present ill-structured problems with competing criteria to ensure at least three valid solutions exist in your math or science classes. For example: "Determine the most efficient bus route given fuel costs, student walk-time limits, and traffic patterns." Multiple mathematical models work here, each with different trade-offs. This transforming questions into problem-solving challenges approach develops higher order thinking skills and meets Webb's Depth of Knowledge level four through authentic complexity.

Use this protocol in your classroom. Present the problem and require groups to brainstorm five possible approaches. Have them defend their top two choices using a weighted criteria matrix that you provide. Finally, ask them to synthesize a hybrid solution that combines the best elements. Each step forces students to articulate their reasoning and negotiate between competing priorities. Your goal is process excellence, not answer conformity, which builds true critical thinking capacity and intellectual flexibility.

Step 4 — How Do You Embed Thinking Routines Into Daily Instruction?

Embed thinking routines using Project Zero's protocols like Claim-Support-Question or Circle of Viewpoints for 7-10 minutes daily. Start with teacher modeling for two weeks, transition to sentence starters, then facilitate student-generated questions using the Question Formulation Technique until routines become automatic cognitive habits.

Start with one routine weekly for 10-15 minutes during your first month. By week four, shift to daily 7-10 minute protocols. These HOTS teaching strategies must become as predictable as taking attendance. Students should know that Tuesday's primary source analysis always opens with Claim-Support-Question before they even enter the room.

Visible Thinking Routines for Metacognition

Use Claim-Support-Question when analyzing primary sources—students make a claim about a historical document, provide textual evidence, then pose one remaining question. In science, deploy Connect-Extend-Challenge after labs: connect to prior knowledge, extend the concept to new contexts, identify assumptions that challenge their understanding. For project launches, try Compass Points (E=excitements, W=worries, N=needs, S=stance/suggestions) to surface initial thinking.

These visual thinking strategies for the classroom push students up Bloom's taxonomy from recall into analysis. When my 7th graders analyzed the Boston Massacre engraving using Claim-Support-Question, they stopped asking "What happened?" and started debating "Whose perspective is missing from this image?" That's when critical thinking replaces guessing.

Collaborative Reasoning Protocols

Assign cognitive roles during Think-Pair-Share to ensure higher order thinking skills develop through peer interaction. Designate one partner as the Analyzer who breaks down the text, the other as the Evaluator who judges the evidence. Use Save the Last Word for Me during literature circles. Each student selects a passage, shares it, hears others interpret it first, then gets the final word on their own thinking.

Try Structured Academic Controversy for contentious topics. Groups of four research assigned positions, present arguments, then switch sides to argue the opposite view before dropping positions to synthesize consensus. This builds critical thinking and raises cognitive demand beyond recall. Unlike traditional debate, this protocol requires students to genuinely understand both perspectives rather than simply defend prior opinions.

Transitioning From Teacher-Led to Student-Driven Inquiry

Apply gradual release to the thinking routines themselves, not just content, to increase cognitive demand. Weeks 1-2: Model metacognition aloud using "I'm noticing... I'm wondering..." while students observe. Weeks 3-4: Provide sentence starters like "I analyzed this by..." or "One evaluation criterion is..." during student-driven inquiry-based learning activities. By week 5, students generate their own questions using the Question Formulation Technique from the Right Question Institute.

Establish the "three-before-me" rule: students must ask three higher-order questions before you answer recall-level queries. When Sarah asked me last October why the Treaty of Versailles failed, I responded, "What's your claim, and what three questions did your group pose first?" She returned with evidence about economic penalties. That's when you know the routine has stuck.

Step 5 — Build Assessment Methods That Capture Complex Thinking

Most tests reward recall. Flip that. Shift your balance from 80% selected response to 60% constructed response and performance tasks. Make higher order thinking skills assessments worth 40% of the final grade. When grades depend on analysis and evaluation, students prioritize those thinking skills in education pdf moments over cramming facts. The shift signals what you actually value.

Designing Performance-Based Assessments

Use thinking tools for students like the GRASPS framework to design authentic challenges. Map out the Goal, Role, Audience, Situation, Product, and Standards. Example: As urban planners (role), students design a water management system (scenario) to present to the school board (audience) that cuts costs by 15% (constraint) while meeting EPA standards. This is performance-based assessment methods that mirror real professional work and demand sustained inquiry rather than one-night cramming.

Vary the task types to target different cognitive moves. Ask students to defend a position using evidence from conflicting primary sources, forcing them to weigh credibility. Have them design solutions to authentic local problems rather than textbook hypotheticals. Let them create documentaries or podcasts requiring scriptwriting and source evaluation. These formats force Bloom's taxonomy synthesis and creation, not just recognition of isolated facts.

Rubrics That Measure Cognitive Process Not Just Product

Separate the thinking from the glitter. Build analytic rubrics with distinct trait categories: Quality of Reasoning (0-4: logical deductions valid and complex), Use of Evidence (0-4: multiple sources integrated seamlessly), and Consideration of Alternatives (0-4: addresses counterarguments thoroughly). Each trait stands alone and feeds separate gradebook columns.

Yes, performance tasks take 3-5x longer to grade than multiple choice. Train students in peer assessment using your analytical rubrics. When partners justify scores using trait-specific language, grading burden drops by 40%. Students learn the criteria while you reclaim planning time.

Never use holistic rubrics. They hide cognitive gaps behind a single score. A student might submit a beautiful poster earning an A for Product Quality while demonstrating circular reasoning worth a C for Cognitive Process. Analytic rubrics expose that disparity immediately. Check analyzing student assessment data to track these splits across units and spot where critical thinking breaks down before it calcifies.

Using Formative Checks to Adjust Instruction

Check thinking daily, not just at the unit end. Deploy exit tickets requiring genuine analysis: "What pattern did you notice in the data?" or "What's the most significant limitation of today's solution?" If fewer than 60% of your class hits level 4 on your reasoning scale, stop. Reteach using a different modality before advancing to new content. This responsive loop protects metacognition development.

Deploy digital thinking tools for students for rapid formative checks. Google Forms with branching logic let students self-assess against rubric traits. Padlet surfaces collaborative analysis of visible thinking. Flipgrid captures oral defense of reasoning against Webb's Depth of Knowledge criteria. These reveal cognitive demand gaps that multiple choice masks, letting you adjust tomorrow's plan before misconceptions harden.

Common Mistakes That Undermine Higher Order Thinking Development

Moving to Complex Tasks Without Adequate Scaffolding

You cannot ask students to synthesize three texts when they still struggle to cite evidence from one. I learned this last fall with my 7th graders. Their synthesis essays failed because I skipped the scaffolding sequence.

If success rates drop below forty percent, your task is under-scaffolded. Hattie's research shows gradual release has an effect size of 0.58. Return to modeling. Have students practice finding evidence, then matching claims, then organizing multiple claims before attempting full synthesis.

Assessing Only the Final Answer Instead of the Reasoning

Grading only the final answer trains students to hide their thinking. In my Algebra classes, I used to mark answers wrong without examining the wreckage. Now I require written explanations worth thirty percent of the total score.

This reveals their metacognition. Try error analysis assignments where students correct worked examples containing intentional mistakes. They demonstrate critical thinking by identifying the misstep without pressure. You see their reasoning process clearly, and they learn that wrong answers contain useful data.

Providing Insufficient Wait Time for Cognitive Processing

Your wait time is probably killing your questions. Research shows teachers average 0.9 seconds before jumping in, but higher order thinking skills need three to five seconds minimum. Novel complex questions demand ten to fifteen seconds of uninterrupted think time.

I use a stopwatch now. Ask your question, wait ten seconds in silence, allow sixty-second partner discussion, then call on students. This protocol transforms surface answers into deep analysis. For more on improving student focus and wait time, see our guide.

The Bottom Line on Higher Order Thinking Skills

You don't need a new curriculum to teach higher order thinking skills. You need new questions. That audit you did in Step 1 likely revealed you're asking more recall questions than you realized. Shift just three questions per lesson from "what happened" to "why did it happen" and "how do you know," and you raise the cognitive demand without adding prep time.

Stop treating critical thinking as a special Friday activity. Embed it into Tuesday's grammar lesson and Wednesday's math warm-up using the routines from Step 4. When students explain their reasoning daily, metacognition becomes a habit instead of a performance. Just remember: if your assessments only reward right answers, students will game the system. Match your tests to the complex thinking you actually want to see.

Bloom's taxonomy isn't a checklist to climb every day. It's a reminder that remembering is the foundation, not the destination. Start with what students know, then push them to analyze and evaluate. That's the transformation.

Understanding the Foundation of Higher Order Thinking

Defining the Six Cognitive Levels

Anderson and Krathwohl's revised Bloom's Taxonomy gives us six rungs to climb. At the bottom, Remember asks students to define or list—like when your fourth graders recite times tables from memory or label parts of a cell diagram. Understand moves to classifying and summarizing, such as explaining the causes of the Civil War in their own words without copying the textbook.

Apply means executing and implementing procedures with precision. Students use the Pythagorean theorem to solve real-world measurement problems they haven't seen before. Analyze requires them to differentiate and organize—comparing mitosis versus meiosis in a detailed Venn diagram or sorting primary sources by reliability and bias. Evaluate demands critique and systematic testing, like assessing whether a historical account holds up when cross-checked with artifacts and other documents.

At the top, Create involves designing and constructing original work from scratch. Your eighth graders compose argumentative essays with cited evidence defending a nuanced claim, or design osmosis experiments testing original variables they selected independently. This is where cognitive levels and development strategies shift from consuming knowledge to building new understanding. These thinking skills separate simple recall from the critical thinking we actually want students to own.

The Difference Between Difficult and Complex Tasks

Harder is not the same as complex. A difficult task loads working memory with extra steps but follows a known algorithm you have practiced. Calculating fifty compound interest problems taxes stamina yet requires only one formula applied repeatedly. Five-digit long division works the same way every single time. These tasks challenge concentration without demanding independent judgment.

Complex tasks present competing variables and no single pathway forward. Designing a school recycling program with strict budget limits and space constraints forces students to prioritize conflicting criteria. Determining which investment strategy optimizes growth requires balancing inflation rates, risk tolerance, and liquidity needs simultaneously. The student must develop new criteria rather than follow old ones.

Use this decision matrix: if the work requires following a memorized procedure, you have cognitive demand but not higher order thinking skills. If it requires students to invent the procedure, weigh trade-offs, and justify their reasoning with evidence, you have true complexity. Difficult tasks consume mental energy; complex tasks build metacognition and visible thinking that transfers.

Prerequisites for Student Readiness

Before you push for analysis, check the foundation. Students need roughly eighty percent accuracy on level two Understand tasks before they can handle level four Analyze work in your classroom. Research indicates experts hold over fifty thousand domain-specific knowledge chunks; novices need time to build that schema. John Hattie's meta-analyses show prior achievement carries an effect size of 0.60 for predicting success with complex tasks.

Administer a diagnostic with ten items spanning levels one through four. Students ready for thinking based learning answer eight out of ten level two items correctly and can verbalize their problem-solving process without prompting or hinting. Working memory must juggle three to four variables simultaneously without crashing under the load.

Look for three specific behaviors during your observation. The student explains reasoning using "because" statements that connect evidence to claims. They spot logical errors in worked examples you display on the board. They transfer the skill to a novel context with seventy percent accuracy or better. Miss these markers and your Webb's Depth of Knowledge level four lesson will crash against working memory limits.

Step 1 — Audit Your Current Questioning Patterns

Map Your Existing Questions Against Bloom's Taxonomy

Record one 45-minute lesson on your phone. Transcribe every question you ask. You will likely find 25 to 40 questions in a typical class period. Code each one using Bloom's Taxonomy verb lists. Calculate your current ratio of Remember/Understand questions versus Analyze/Evaluate/Create prompts. Most teachers hover around 70 percent low-level questioning. Aim to flip that to 60 percent higher-order by semester's end.

Use a color-highlighting system. Mark levels 1-2 in pink, levels 3-4 in yellow, and levels 5-6 in green. Tally the frequencies. You can use the TAG (Taxonomy Assessment Grid) or a simple spreadsheet with dropdown menus for rapid coding. I prefer Google Sheets with conditional formatting that turns cells pink automatically when I type "Remember." Here is the tracking template:

Question Text | Bloom Level (1-6) | Student Response Word Count | Wait Time (seconds) | Follow-up Strategy Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

What is the main idea? | 1 | 3 | 2 | None |

How would you test this hypothesis? | 5 | 45 | 8 | Probing for evidence |

Analyze Student Response Patterns

If 80 percent of student responses are single words or phrases, your questioning is likely stuck at levels 1-2. When students generate novel questions or use disciplinary vocabulary spontaneously, you have reached level 4 or above. This visible thinking signals that your thinking strategies are working.

Track the average word count per response. For higher order thinking skills to develop, target 15 or more words per answer. Count how often students ask each other questions instead of funneling everything through you. Note when they request clarification or demand evidence from peers. These metacognition markers reveal true cognitive demand.

Review your audio recording at double speed. Mark the timestamp each time a student speaks uninterrupted for more than 10 seconds. Those long turns indicate higher-order processing is actually happening. Last fall, I discovered my 7th graders spoke in 45-second bursts during argumentation tasks but only 3-second bursts during review games. The data does not lie.

Identify Cognitive Bottlenecks in Your Curriculum

Map your sequence of 10 consecutive lessons. Look for cognitive cliffs where tasks jump from level 2 to level 5 without warning. For example, you might ask students to summarize causes one day and immediately demand they evaluate the most significant cause the next. That gap crushes critical thinking development and leaves students stranded.

Insert bridge activities to close these gaps. Add comparison tasks at level 4 before asking for evaluations at level 5. Let students analyze the relative weight of factors before judging significance. This scaffolding prevents the frustration that shuts down inquiry. For more on building these bridges, explore these teaching critical thinking strategies.

Check your scope and sequence for Webb's Depth of Knowledge alignment. A healthy progression moves students through application and analysis before demanding creation. When you spot a cliff, drop in a visible thinking routine. Graphic organizers for comparing sources work wonders before synthesis essays.

Step 2 — Select a Thinking Framework That Fits Your Subject

Bloom's Taxonomy vs. Webb's Depth of Knowledge

Bloom's Taxonomy sorts thinking by cognitive process. It moves from Remember through Create, focusing on what skill the student uses. Webb's Depth of Knowledge measures cognitive demand—how deeply the content must be processed. Webb offers four levels: Recall, Skills/Concepts, Strategic Thinking, and Extended Thinking. Bloom's Create aligns with Webb's DOK 4, both demanding extended thinking. However, Bloom's Analyze can land at DOK 2 or 3 depending on context. DOK levels 3 and 4 align with higher order thinking skills but emphasize how deeply students must interact with the content rather than which verb they use.

State education departments often publish thinking skills in education pdf guides that map these alignments side-by-side for easy reference. Choose Bloom when building skill sequences and writing lesson objectives. Choose Webb when aligning assessments to NGSS or CCSS standards. STEM subjects benefit from Webb's clarity on mathematical modeling and scientific inquiry. Humanities subjects work better with Bloom for developing rhetorical analysis and argumentation where the intellectual move matters more than the content complexity.

Subject-Specific Modifications

Science teachers should layer NGSS Science and Engineering Practices alongside Bloom. Focus on Developing and Using Models at DOK 3 and Constructing Explanations at DOK 4. These practices make the abstract concrete when students build physical or computational models rather than just memorizing facts about phenomena. For ELA, add the Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework. Its Elements of Thought—purpose, question, information, inference, assumption, and point of view—layer cleanly over Bloom's levels. When students analyze a text, they identify assumptions and implications rather than just listing examples.

This adds rigor to literary essays by forcing students to examine their own critical thinking processes. Art teachers should adopt Studio Thinking from Project Zero. The Eight Habits of Mind include Engage and Persist, Envision, Observe, and Reflect. These visible thinking routines build metacognition while students work through creative problems. Downloadable charts from Project Zero serve as thinking skills in education pdf references you can keep at your planning desk or share with parents during conferences.

Creating a Common Language for Your Classroom

Develop a classroom lexicon that sticks. Choose three thinking strategies per week and weave them into your instructions across subjects. When students hear Evaluate used consistently in math, reading, and science, they recognize critical thinking as a transferable skill rather than a subject-specific trick. Keep the language consistent from September through June. Build a visual word wall with icons. Place a magnifying glass next to Analyze, a balance scale next to Evaluate, and construction tools next to Create. Add sentence starters for each level so students know how to enter the conversation.

Post these at eye level where students can reference them during independent work or peer discussions. Run a five-minute verb warm-up daily. Students use the target thinking verb three times in conversation before you begin the lesson. This primes their brains for higher order thinking skills work. When developing adaptive thinking skills becomes routine, students stop guessing what you want and start knowing how to think through problems systematically rather than hunting for right answers.

Step 3 — How Do You Transform Low-Level Questions Into Higher Order Challenges?

Transform low-level questions by adding conditional scenarios ('how would this change if...'), requiring cross-context comparison, or removing given information. For example, change 'What is the main idea?' to 'How would the main idea shift if the protagonist chose differently?' This forces conditional reasoning and evidence-based speculation rather than simple retrieval.

Three upgrades consistently raise cognitive demand in your classroom. First, append a conditional clause: "How would X change if Y occurred?" Second, force comparison across contexts: "Contrast X with Z situation." Third, strip away given information: "Solve without using the quadratic formula." Each method requires students to manipulate knowledge rather than simply retrieve it.

In your seventh-grade history class, replace "When did the Civil War begin?" with "How would the war's trajectory differ if it had begun in 1850 versus 1861?" The original asks for a date. Your revised version demands critical thinking about economic readiness, political tensions, and military capacity across two distinct timelines.

Converting Recall Questions to Analysis Prompts

Move beyond memorization by injecting causality, perspective shifts, or categorization demands into your questions. Ask "What caused X to lead to Y?" or "How would X appear from an opposing viewpoint?" Alternatively, require sorting: "Which category of economic system does this represent and why?" These shifts immediately activate metacognition as students must justify their classifications. You ensure they cannot answer without processing relationships between disconnected concepts.

Watch this progression in your biology class. Instead of "Name the parts of a cell," ask "Which organelles would be most affected by a toxin blocking protein synthesis and why?" Your students still need to know the organelles, but now they must apply that knowledge to a novel scenario. This hits Bloom's taxonomy analysis level and mirrors authentic scientific reasoning rather than flashcard recall.

Adding Constraints to Spark Creative Evaluation

Limit resources to force creative evaluation in your assessments. Impose a fifty-dollar budget, a twenty-four-hour deadline, or ethical boundaries like "solution cannot displace existing residents." Material limits work too: "Build this using only paper and tape." These constraints mirror authentic engineering problems and elevate visible thinking as students navigate trade-offs. When you remove their default tools, you force innovation and prioritize what truly matters.

Replace the generic prompt "Evaluate this argument" with "Evaluate this argument using only evidence from primary sources dated before 1950, considering the author's economic status." Suddenly your students cannot rely on generalizations or hindsight. They must weigh historical context against available data, a core component of hots teaching strategies that builds historical empathy and rigorous source literacy simultaneously.

Designing Questions With Multiple Valid Pathways

Present ill-structured problems with competing criteria to ensure at least three valid solutions exist in your math or science classes. For example: "Determine the most efficient bus route given fuel costs, student walk-time limits, and traffic patterns." Multiple mathematical models work here, each with different trade-offs. This transforming questions into problem-solving challenges approach develops higher order thinking skills and meets Webb's Depth of Knowledge level four through authentic complexity.

Use this protocol in your classroom. Present the problem and require groups to brainstorm five possible approaches. Have them defend their top two choices using a weighted criteria matrix that you provide. Finally, ask them to synthesize a hybrid solution that combines the best elements. Each step forces students to articulate their reasoning and negotiate between competing priorities. Your goal is process excellence, not answer conformity, which builds true critical thinking capacity and intellectual flexibility.

Step 4 — How Do You Embed Thinking Routines Into Daily Instruction?

Embed thinking routines using Project Zero's protocols like Claim-Support-Question or Circle of Viewpoints for 7-10 minutes daily. Start with teacher modeling for two weeks, transition to sentence starters, then facilitate student-generated questions using the Question Formulation Technique until routines become automatic cognitive habits.

Start with one routine weekly for 10-15 minutes during your first month. By week four, shift to daily 7-10 minute protocols. These HOTS teaching strategies must become as predictable as taking attendance. Students should know that Tuesday's primary source analysis always opens with Claim-Support-Question before they even enter the room.

Visible Thinking Routines for Metacognition

Use Claim-Support-Question when analyzing primary sources—students make a claim about a historical document, provide textual evidence, then pose one remaining question. In science, deploy Connect-Extend-Challenge after labs: connect to prior knowledge, extend the concept to new contexts, identify assumptions that challenge their understanding. For project launches, try Compass Points (E=excitements, W=worries, N=needs, S=stance/suggestions) to surface initial thinking.

These visual thinking strategies for the classroom push students up Bloom's taxonomy from recall into analysis. When my 7th graders analyzed the Boston Massacre engraving using Claim-Support-Question, they stopped asking "What happened?" and started debating "Whose perspective is missing from this image?" That's when critical thinking replaces guessing.

Collaborative Reasoning Protocols

Assign cognitive roles during Think-Pair-Share to ensure higher order thinking skills develop through peer interaction. Designate one partner as the Analyzer who breaks down the text, the other as the Evaluator who judges the evidence. Use Save the Last Word for Me during literature circles. Each student selects a passage, shares it, hears others interpret it first, then gets the final word on their own thinking.

Try Structured Academic Controversy for contentious topics. Groups of four research assigned positions, present arguments, then switch sides to argue the opposite view before dropping positions to synthesize consensus. This builds critical thinking and raises cognitive demand beyond recall. Unlike traditional debate, this protocol requires students to genuinely understand both perspectives rather than simply defend prior opinions.

Transitioning From Teacher-Led to Student-Driven Inquiry

Apply gradual release to the thinking routines themselves, not just content, to increase cognitive demand. Weeks 1-2: Model metacognition aloud using "I'm noticing... I'm wondering..." while students observe. Weeks 3-4: Provide sentence starters like "I analyzed this by..." or "One evaluation criterion is..." during student-driven inquiry-based learning activities. By week 5, students generate their own questions using the Question Formulation Technique from the Right Question Institute.

Establish the "three-before-me" rule: students must ask three higher-order questions before you answer recall-level queries. When Sarah asked me last October why the Treaty of Versailles failed, I responded, "What's your claim, and what three questions did your group pose first?" She returned with evidence about economic penalties. That's when you know the routine has stuck.

Step 5 — Build Assessment Methods That Capture Complex Thinking

Most tests reward recall. Flip that. Shift your balance from 80% selected response to 60% constructed response and performance tasks. Make higher order thinking skills assessments worth 40% of the final grade. When grades depend on analysis and evaluation, students prioritize those thinking skills in education pdf moments over cramming facts. The shift signals what you actually value.

Designing Performance-Based Assessments

Use thinking tools for students like the GRASPS framework to design authentic challenges. Map out the Goal, Role, Audience, Situation, Product, and Standards. Example: As urban planners (role), students design a water management system (scenario) to present to the school board (audience) that cuts costs by 15% (constraint) while meeting EPA standards. This is performance-based assessment methods that mirror real professional work and demand sustained inquiry rather than one-night cramming.

Vary the task types to target different cognitive moves. Ask students to defend a position using evidence from conflicting primary sources, forcing them to weigh credibility. Have them design solutions to authentic local problems rather than textbook hypotheticals. Let them create documentaries or podcasts requiring scriptwriting and source evaluation. These formats force Bloom's taxonomy synthesis and creation, not just recognition of isolated facts.

Rubrics That Measure Cognitive Process Not Just Product

Separate the thinking from the glitter. Build analytic rubrics with distinct trait categories: Quality of Reasoning (0-4: logical deductions valid and complex), Use of Evidence (0-4: multiple sources integrated seamlessly), and Consideration of Alternatives (0-4: addresses counterarguments thoroughly). Each trait stands alone and feeds separate gradebook columns.

Yes, performance tasks take 3-5x longer to grade than multiple choice. Train students in peer assessment using your analytical rubrics. When partners justify scores using trait-specific language, grading burden drops by 40%. Students learn the criteria while you reclaim planning time.

Never use holistic rubrics. They hide cognitive gaps behind a single score. A student might submit a beautiful poster earning an A for Product Quality while demonstrating circular reasoning worth a C for Cognitive Process. Analytic rubrics expose that disparity immediately. Check analyzing student assessment data to track these splits across units and spot where critical thinking breaks down before it calcifies.

Using Formative Checks to Adjust Instruction

Check thinking daily, not just at the unit end. Deploy exit tickets requiring genuine analysis: "What pattern did you notice in the data?" or "What's the most significant limitation of today's solution?" If fewer than 60% of your class hits level 4 on your reasoning scale, stop. Reteach using a different modality before advancing to new content. This responsive loop protects metacognition development.

Deploy digital thinking tools for students for rapid formative checks. Google Forms with branching logic let students self-assess against rubric traits. Padlet surfaces collaborative analysis of visible thinking. Flipgrid captures oral defense of reasoning against Webb's Depth of Knowledge criteria. These reveal cognitive demand gaps that multiple choice masks, letting you adjust tomorrow's plan before misconceptions harden.

Common Mistakes That Undermine Higher Order Thinking Development

Moving to Complex Tasks Without Adequate Scaffolding

You cannot ask students to synthesize three texts when they still struggle to cite evidence from one. I learned this last fall with my 7th graders. Their synthesis essays failed because I skipped the scaffolding sequence.

If success rates drop below forty percent, your task is under-scaffolded. Hattie's research shows gradual release has an effect size of 0.58. Return to modeling. Have students practice finding evidence, then matching claims, then organizing multiple claims before attempting full synthesis.

Assessing Only the Final Answer Instead of the Reasoning

Grading only the final answer trains students to hide their thinking. In my Algebra classes, I used to mark answers wrong without examining the wreckage. Now I require written explanations worth thirty percent of the total score.

This reveals their metacognition. Try error analysis assignments where students correct worked examples containing intentional mistakes. They demonstrate critical thinking by identifying the misstep without pressure. You see their reasoning process clearly, and they learn that wrong answers contain useful data.

Providing Insufficient Wait Time for Cognitive Processing

Your wait time is probably killing your questions. Research shows teachers average 0.9 seconds before jumping in, but higher order thinking skills need three to five seconds minimum. Novel complex questions demand ten to fifteen seconds of uninterrupted think time.

I use a stopwatch now. Ask your question, wait ten seconds in silence, allow sixty-second partner discussion, then call on students. This protocol transforms surface answers into deep analysis. For more on improving student focus and wait time, see our guide.

The Bottom Line on Higher Order Thinking Skills

You don't need a new curriculum to teach higher order thinking skills. You need new questions. That audit you did in Step 1 likely revealed you're asking more recall questions than you realized. Shift just three questions per lesson from "what happened" to "why did it happen" and "how do you know," and you raise the cognitive demand without adding prep time.

Stop treating critical thinking as a special Friday activity. Embed it into Tuesday's grammar lesson and Wednesday's math warm-up using the routines from Step 4. When students explain their reasoning daily, metacognition becomes a habit instead of a performance. Just remember: if your assessments only reward right answers, students will game the system. Match your tests to the complex thinking you actually want to see.

Bloom's taxonomy isn't a checklist to climb every day. It's a reminder that remembering is the foundation, not the destination. Start with what students know, then push them to analyze and evaluate. That's the transformation.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.