Inquiry Based Learning Strategies: Implementation Guide

Inquiry Based Learning Strategies: Implementation Guide

Inquiry Based Learning Strategies: Implementation Guide

Article by

Milo

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

ESL Content Coordinator & Educator

All Posts

Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve shows we lose 70% of new information within 24 hours. That’s why your brilliant lecture on photosynthesis last Tuesday disappeared by Wednesday’s bell. Inquiry based learning strategies flip this script. Students build knowledge themselves instead of receiving it passively. When kids wrestle with essential questions and hunt for evidence, they encode learning deeper than any PowerPoint can reach. You see it in their faces when the concept clicks. They own the work because they built it with their own hands.

I’ve watched 7th graders forget entire units of direct instruction. They remember every detail of a guided inquiry project from October. The difference is ownership. This isn’t magic. It’s constructivist pedagogy in action. The framework I’ll walk you through here starts with solid prerequisites. Then we move through framing compelling questions, designing scaffolded instruction, and managing evidence collection without you becoming the answer key. I’ll show you how to facilitate without taking over. We’ll finish with helping students synthesize findings into real conclusions. You’ve probably tried pieces of this before. Now we’ll put them together so discovery learning actually works in your room.

Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve shows we lose 70% of new information within 24 hours. That’s why your brilliant lecture on photosynthesis last Tuesday disappeared by Wednesday’s bell. Inquiry based learning strategies flip this script. Students build knowledge themselves instead of receiving it passively. When kids wrestle with essential questions and hunt for evidence, they encode learning deeper than any PowerPoint can reach. You see it in their faces when the concept clicks. They own the work because they built it with their own hands.

I’ve watched 7th graders forget entire units of direct instruction. They remember every detail of a guided inquiry project from October. The difference is ownership. This isn’t magic. It’s constructivist pedagogy in action. The framework I’ll walk you through here starts with solid prerequisites. Then we move through framing compelling questions, designing scaffolded instruction, and managing evidence collection without you becoming the answer key. I’ll show you how to facilitate without taking over. We’ll finish with helping students synthesize findings into real conclusions. You’ve probably tried pieces of this before. Now we’ll put them together so discovery learning actually works in your room.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Prerequisites — Establishing the Foundation for Inquiry Based Learning

Creating Psychological Safety for Intellectual Risk-Taking

You can't launch into inquiry based learning strategies on day one. I learned that the hard way with my 7th graders who shut down the moment I asked them to "wonder" about chemical reactions. They needed permission to be wrong first.

Block out three to five class periods upfront. Forty-five minutes each. That's the investment that makes inquiry based learning and constructivism actually work in a real classroom with real kids who've been trained to raise hands for correct answers.

I open with Columbia University's Community Agreements. I post four non-negotiables: All ideas get a five-minute testing period, no killer phrases like "that won't work," we build with "Yes, and..." not "but," and confusion is data not failure. We practice these with low-stakes improv games before touching content. One student suggests we study pizza instead of cells; another adds "Yes, and we could measure the yeast respiration." That's the protocol working.

The Circle of Viewpoints routine from Harvard Project Zero changes everything. Before we investigate anything, students physically move to different spots in the room to argue from the perspective of the mitochondria, the lab safety inspector, or the budget-conscious principal. It trains them to hold multiple hypotheses without committing to one immediately.

That's pure constructivist pedagogy in action—Piaget's cognitive conflict theory suggests we learn when our existing models clash with new evidence. If kids won't voice their initial models, that conflict never happens. We are literally manufacturing the disequilibrium Piaget described.

Failure logs are non-negotiable in my guided inquiry setup. Each student records three unsuccessful attempts before declaring success. Last October, Maria documented her three bridge designs that collapsed before the fourth held weight. When she presented, she led with the failures. The class nodded along because their failure logs looked similar. This models Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development—we scaffold intellectual risk by making struggle visible and shared.

Before opening the first investigation, run the Question Formulation Technique. Students generate questions following four rules: ask as many as possible, don't stop to judge, write exactly as spoken, and change statements into questions. We do this with random objects—a paperclip, a leaf—so the stakes stay low. By week two, they're ready to attack essential questions about erosion or civil rights using the same muscle.

Organizing Physical Space and Resources for Investigation

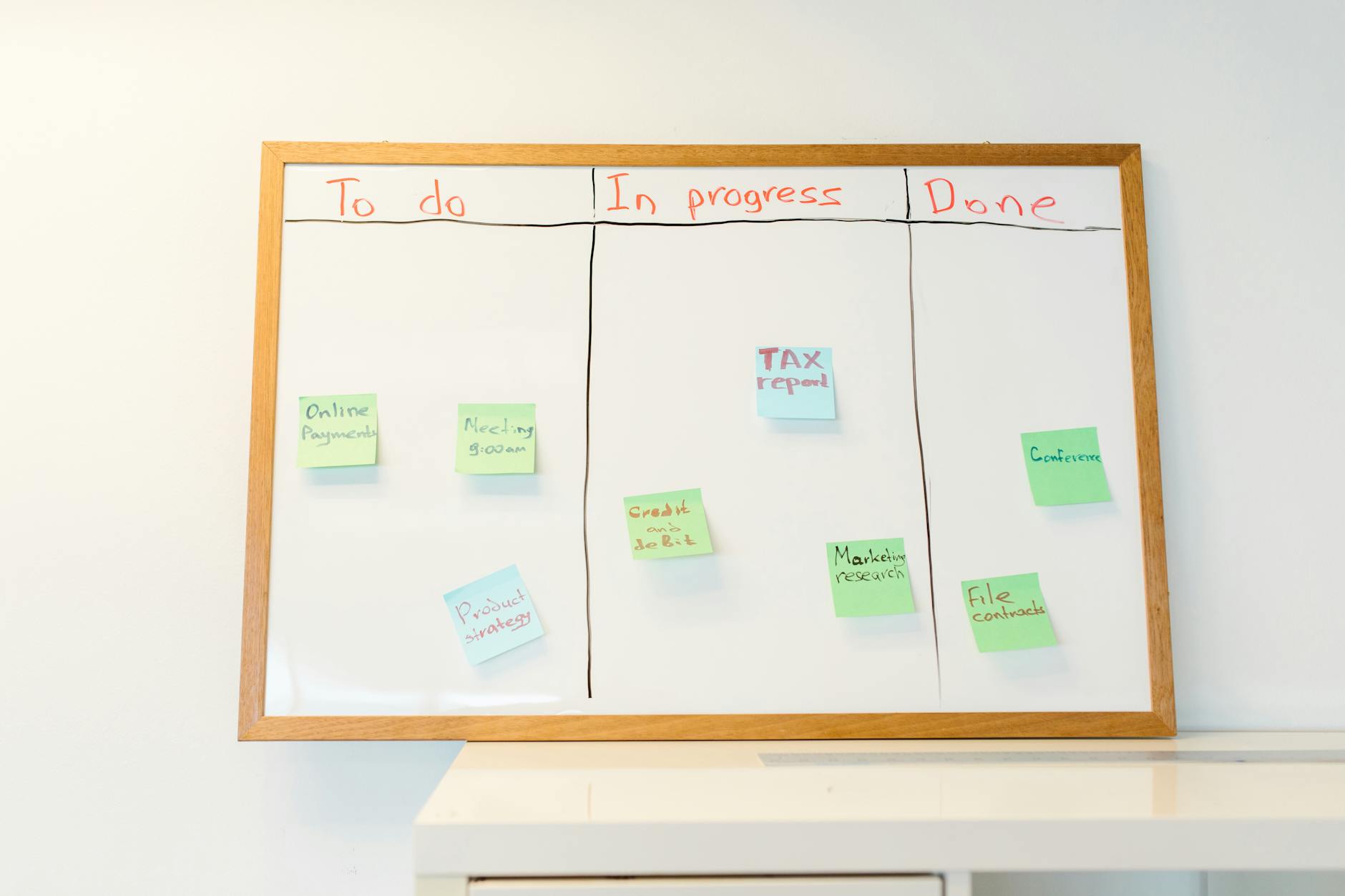

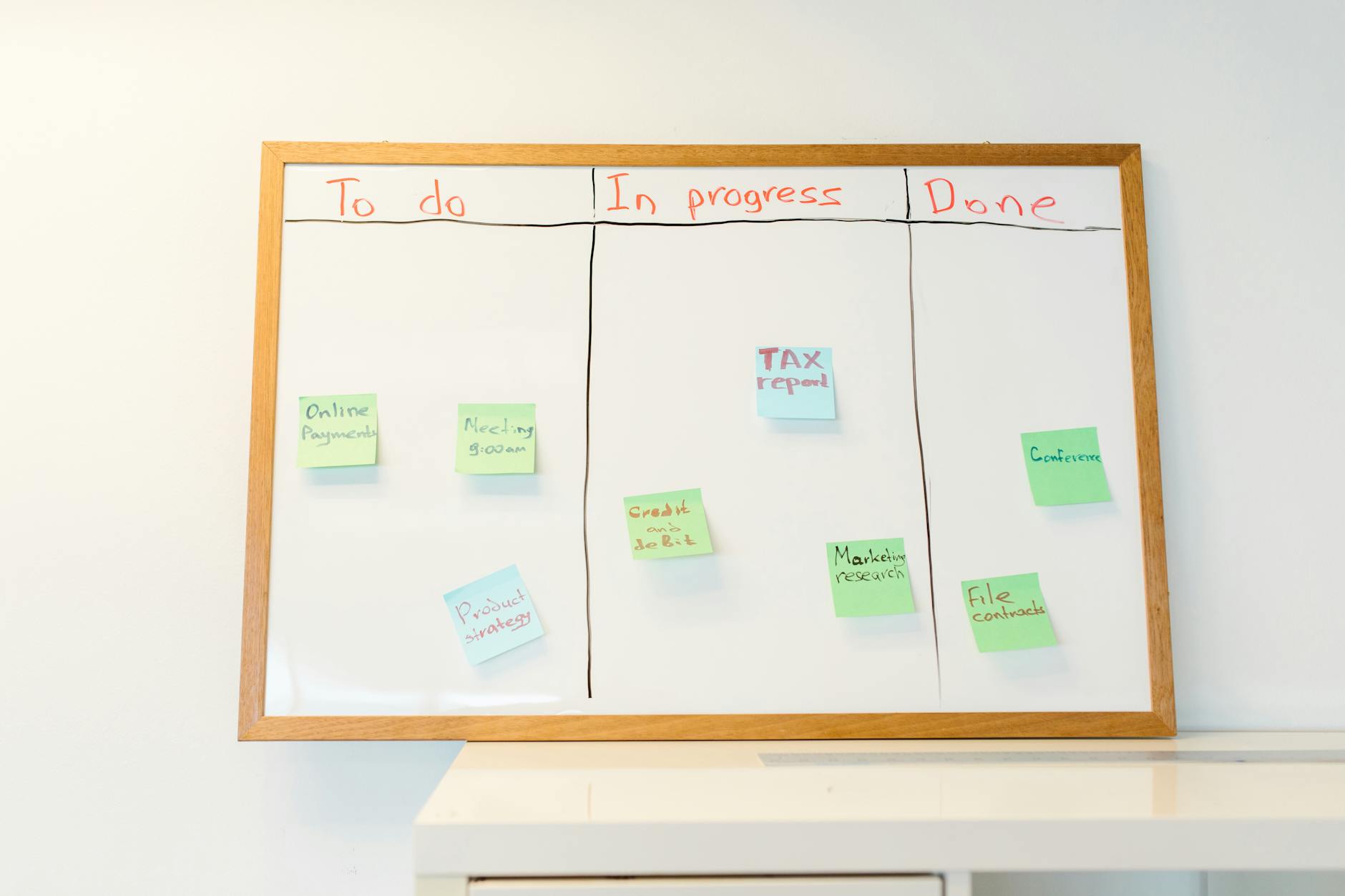

Your room layout signals how inquiry based instructional strategies actually work. I rearrange my classroom for 28 to 32 students into six investigation clusters, each with a home base table of five or six kids. They can see all four to six activity stations from their seats without craning necks. This matters because wandering wastes time and breaks focus.

Each investigation station functions as a dedicated resource hub with clear sightlines from the home bases. I stock five to seven toolkits at each of the four to six stations. Station one holds exactly five digital scales, measurement tapes, and calculation journals. Station two has primary source bins with 1900s immigration photos and magnifying glasses. Station three contains circuit boards and multimeters.

When tools have specific homes using the mise en place method, decision paralysis disappears. Kids grab and go instead of hunting through cluttered bins.

Budget $200 to $500 for reusable equipment upfront. Digital scales run $25 each. Plastic bins cost $5 at Target. Primary source prints are free from the Library of Congress. That's your inquiry based learning methods starter pack. You're set for three years of discovery learning.

Maintain a 60/40 split of digital to physical resources. I keep one device for every two students, but every station has offline backups stored in the resource hub. When the Wi-Fi crashes during a measurement lab, students reach for the analog rulers and graph paper taped underneath the tables. Equity means inquiry continues whether the internet cooperates or not. Check out effective classroom design and learning zones for layout diagrams that actually fit 30+ desks.

Front-load three to five class periods—forty-five minutes each—to establish these systems. Day one covers the Community Agreements. Day two practices the failure logs with a simple tower-building challenge. Day three introduces the Question Formulation Technique with that paperclip. By day four, when you finally unveil the essential question about kinetic energy, they're ready to investigate instead of asking "how do we start?" That's scaffolded instruction done right. The preparation feels invisible because you built it beforehand. When they finally sit for a Socratic seminar in week three, the protocols feel automatic.

Step 1 — Frame Compelling Questions That Drive Investigation

Essential questions transfer across years: "How do communities balance competing needs?" Supporting questions make investigation possible. For 7th-grade watersheds, pair that with "What percentage of our river’s pollution comes from agricultural runoff?" Match "Who decides how land gets used?" with "Which zoning laws changed in our county since 1990?" Pair "Why do ecosystems change?" with "How did wolf removal affect Yellowstone’s vegetation?"

I use the Question Formulation Technique for student-generated entry points. It’s a 30-minute protocol with four rules: ask as many as you can, do not judge or answer them, record every question exactly as asked, and change statements into questions. I give a Question Focus like "Our cafeteria wastes 200 pounds of food weekly," and set a 10-minute timer.

Before committing, students run the feasibility filter. Can we access data within two weeks? Does it require ethical approval? Is it testable? Then I provide grade-specific stems. K-2 asks "Why do..." Third through fifth uses "What happens when..." Sixth through eighth frames "How does X affect Y..." High school tackles "To what extent..."

Crafting Essential Questions That Spark Curiosity

Wiggins and McTighe’s six facets help me test my questions. Can students explain it? Interpret through art? Apply to their neighborhood? Consider perspectives? Show empathy? Demonstrate self-knowledge? If it hits fewer than three facets, it’s trivia. "Why did the Civil War start?" fails. "How do societies heal after being torn apart?" passes.

I convert closed questions using the How/Why shift. "What is photosynthesis?" becomes "How do organisms convert energy without consuming other living things?" The first gets a textbook paragraph. The second demands comparing autotrophs to heterotrophs. I ban "What is" and "List the." If Google answers it in one sentence, I reframe it into discovery learning.

Then I run the Monday Morning Test. Can students engage before any instruction? Last October, my 7th graders argued for fifteen minutes about "How does where you live affect what you believe?" using only experience. That friction—the not-knowing-yet—pulls them through the unit. No Monday Morning engagement means no inquiry.

This takes practice. My first year, I thought "What is democracy?" was essential. It wasn’t. Now I write questions on Friday and let them sit. If kids won’t argue in the hallway, I rewrite. The best questions feel uncomfortable. That discomfort is the engine of guided inquiry.

Teaching Students to Generate Their Own Investigable Questions

I teach students to climb the Question Ladder before selecting investigations. Level 1 asks facts: "When was the Emancipation Proclamation signed?" Level 2 analyzes: "Why did Lincoln choose that timing?" Level 3 synthesizes: "How might the Civil War have ended differently without that document?" Students generate two at each level before picking one Level 3. This prevents Google-able trivia or impossible research.

Sentence frames help reluctant starters. I post: "I wonder if ____ affects ____ because ____" and "What would happen if we changed ____?" These force students to identify variables. A kid writes, "I wonder if sunlight affects mold growth because I’ve seen bread get fuzzy near windows." That’s investigable. The frames scaffold the move from curiosity to hypothesis without me doing the thinking. This is scaffolded instruction.

We use the 20-10 timeline. Twenty minutes of generation, then ten minutes of peer review using the Thickness Test. Can we find multiple valid answers? One textbook answer means too thin. Three interpretations backed by evidence means thick enough. This protocol is one of my core inquiry based learning strategies for teaching students to generate their own investigable questions.

Last spring, my 8th graders studied local water quality. One group started with "What is pH?"—a Level 1 dead end. Using the ladder and "I wonder if" frame, they landed on "How does agricultural runoff affect stream pH near farms versus forests?" That’s testable. Find more inquiry-based teaching examples here. Don’t hand them the question. They must build it.

Step 2 — Design Scaffolded Discovery Activities

Selecting the Right Level of Inquiry (Structured to Open)

Herron's taxonomy breaks inquiry into four levels running from teacher-heavy to student-driven. Level 0 is confirmation—students verify a known result, like proving vinegar and baking soda make gas. Level 1 is structured inquiry where you pose the question and provide the procedure. Think of an 8th-grade density lab where you give steps but they measure mass and volume.

Level 2 shifts to guided inquiry—you set the problem, but students design the method. Those same 8th graders might test whether fresh or saltwater freezes faster. Level 3 is open inquiry where students pose the question and design the method. Save that for juniors and seniors doing capstones, not middle schoolers.

Picking the wrong level kills momentum. If they finish in ten minutes flat, you over-scaffolded. If they stare at materials for fifteen minutes without touching anything, you went too open. Run a quick safety check first. Have they mastered goggles-and-gloves protocols? If no, stick to Level 1 even if you want to let go. Is the concept foundational? Then apply the 40-40-20 formula: forty percent researching and designing, forty investigating, twenty analyzing. For structured inquiry, flip that to 20-60-20 since the design is mostly done. Selecting the right level of inquiry means matching the autonomy to their readiness, not your idealism.

Curating Resources Without Removing the Intellectual Challenge

Throwing twenty links at kids creates paralysis. Giving them one source kills critical thinking. The Goldilocks Rule sweet spot is five to seven vetted sources. Include one deliberate distractor—maybe a blog post with clear bias about climate change—to force them to evaluate reliability. Build your banks in Padlet or Wakelet and tag them green, yellow, or red for difficulty.

Green hits grade level for struggling readers. Yellow pushes the 1.5 Rule: texts written about a year and a half above grade level work when kids read in pairs. Red sources are college-level abstracts for your advanced kids who need real teeth to bite into.

Set up your investigation banks before the unit starts. Drop in videos, infographics, and primary sources that answer different parts of the driving question. When students hit a roadblock, they learn to navigate the bank before calling you over. This builds the self-sufficiency that constructivist pedagogy demands. It also keeps you from becoming the human search engine.

Timing matters. Handing over procedure sheets at minute zero trains them to follow recipes. Instead, use just-in-time release. Let them wrestle with the design problem for fifteen minutes first. When they hit walls, push out the procedural hints. This keeps the intellectual work on their shoulders while preventing total shutdown. Scarcity breeds dependence; overload breeds copy-paste. Seven sources, one trap, and a fifteen-minute struggle window—that is how you scaffold without stealing the discovery. Inquiry based learning strategies fail when we remove the struggle entirely.

Step 3 — How Do You Facilitate Evidence Collection Without Taking Over?

Facilitate evidence collection by using structured protocols like Conver-Stations or the Harkness Method, where the teacher physically removes themselves from the discussion center. Implement Rowe's Wait Time (3-5 seconds of silence after questions) to force student-to-student dialogue, and enforce the 'Three Before Me' rule requiring students to consult peers and texts before asking you for procedural help.

Your job is to become invisible. Not absent—just peripheral. When you occupy the center, kids look to you for answers. These protocols shift that gravitational pull toward the texts and toward each other.

I learned this the hard way during a Civil War inquiry unit. I kept jumping in to "clarify" at Station 3, and by the end, every group had identical conclusions—mine. Now I run Conver-Stations with four distinct document sets spread around the room. Kids rotate every twelve minutes with a specific collection sheet. I stand near the file cabinets, coffee in hand, literally forcing myself to stay outside the circle.

Rowe's Wait Time feels like torture at first. You ask a question, then count to five in your head while the silence screams. But that pause lets kids process instead of panic. Pair it with the Harkness Method—the oval table setup from Phillips Exeter where you sit outside the rim. I sketch a name map to track who speaks, and I don't break in until the silence hits two full minutes. They always break first.

The Three Before Me rule keeps me from becoming Google. Students must check their textbook, ask a table partner, and search our digital database before they raise a hand for procedural help. Last Tuesday, Marcus started to ask me where to find the primary source about child labor. I pointed at the rule poster. He sighed, turned to Sarah, and found it in ninety seconds. That's the point.

Data Gathering Techniques for Different Grade Levels

Scaffolded instruction means matching the tool to the developmental stage, not dumbing down the thinking. For kindergarten through second grade, I use picture sorting protocols. Each station gets fifteen to twenty laminated images—factories, rivers, faces from history—and tally sheets with icons instead of words. They sort by "Then/Now" or "Happy/Sad" and mark their counts with stickers. The icons let pre-readers work independently while the teacher circulates to listen for reasoning.

Third through fifth graders handle structured observation journals. I print the four-column layout: Observe, Wonder, Connect, Evidence. They sketch what they see in the artifact photo, write one question, link it to a prior reading, and cite the source number. It keeps their hands busy and their brains anchored. I collect these midway through the period to check for off-track assumptions without lecturing.

Middle schoolers need guided inquiry with real teeth. I send them on database scavenger hunts using JSTOR School Edition. They must bring back three cited quotations with page numbers, not just facts. When they realize they can't copy-paste from academic abstracts, they start reading closely. That's when the discovery learning actually starts.

Teaching Critical Source Evaluation Skills

Kids will cite anything that pops up first on Google if you let them. I teach the CRAAP test—Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose—to sixth through twelfth graders using a laminated checklist rubric they keep in their binders. They physically check off each letter before a source enters their notes. It slows them down for exactly three minutes, then saves them from citing Wikipedia in their final essays.

For younger students, I simplify with the Trustworthy Triangle. We ask three questions: Does the author know the topic? Does she tell the truth? Does she want to help us learn? If any corner wobbles, we find a better source. I model this with a ridiculous website about flying sharks to make the red flags obvious.

Speaking of flags, every student gets a critical source evaluation skills card listing the warning signs: missing publication dates, words like "uproarious" or "shocking," and websites ending in .com with no citations. Once they spot these in practice, they start policing each other. That's when I know the inquiry based learning strategies are sticking—they're protecting their own research integrity.

Step 4 — Guide Students to Synthesize Evidence and Draw Conclusions

At this point in your inquiry based research project, kids have gathered evidence. Now they need to make sense of it. I use the Claim-Evidence-Reasoning framework: one claim, three data points, and two sentences explaining the science behind the evidence. It keeps them from listing facts.

Then we climb the So What? ladder: personal relevance, then community impact, then global significance. Last year, my 7th graders traced microplastics from our cafeteria to Arctic seabirds. That third rung hit hard.

For visual synthesis, they map connections using CmapTools or string and cards. They link evidence to claims with yarn. When the web gets messy, they see where reasoning breaks. These inquiry based learning strategies move kids from collecting to connecting.

Using Socratic Questioning to Challenge Assumptions

I keep a tracking sheet listing six categories: Clarification ("What do you mean by..."), Assumption ("What are you assuming..."), Evidence ("What supports..."), Viewpoint ("Is there another way..."), Consequence ("What are the implications..."), and Meta-questions ("Why does this matter?"). I check off each type to ensure variety.

When students run the Socratic seminar, I use a fishbowl. The inner circle discusses while the outer tracks fallacies. I heard a 10th grader pause last week and say, "Wait, I think I'm assuming correlation equals causation." using Socratic questioning to challenge assumptions works best when you release control gradually.

During guided inquiry, I model stems as scaffolded instruction, then hand them the script. By week three, they probe sources without prompts. The constructivist pedagogy sticks when students internalize the habit, not just answer your essential questions.

Connecting Findings to Prior Knowledge and Real-World Applications

Skip the standard KWL chart. I use KWL+—the plus stands for Action. Students effectively use evidence to back up arguments when they know a real audience waits. I have used these in diverse inquiry based lessons, sending kids to city council for inquiry based project examples, science journals, or museum exhibits.

The CER framework shines here. Students write one claim, cite three evidence pieces, then connect to principles in two sentences. I test their conclusion with a transfer task: "If you saw this pattern in economics, what would you predict?" It exposes gaps fast.

Discovery learning falls flat without these bridges. Last semester, students studying water quality realized their data mirrored 19th-century cholera maps. They strung yarn between evidence cards and John Snow's findings. That's synthesis you can see.

Common Pitfalls and How to Troubleshoot Implementation Challenges

When students go off-task five minutes into an investigation, the problem usually isn't motivation—it's the task design. I run a quick diagnostic: too much freedom often means the cognitive load exceeded their working memory. The fix takes five minutes. I add a constraint, like requiring evidence from at least three sources before they move to analysis. That single parameter refocuses the room without killing the inquiry.

I also use a Productive Failure protocol when I see blank stares. I let them struggle with the essential question for twenty minutes. No hints. Then I pause for ten minutes of just-in-time direct instruction targeting the specific gap I observed. We return to the inquiry immediately. This cycle respects constructivist pedagogy while preventing shutdown.

Start with backward design (Wiggins & McTighe) to avoid standards misalignment. I pick two priority standards first, then build the inquiry to require those skills. Last year I targeted RI.7.8 and W.7.1b for an argument unit. Every investigation step required tracing claims and using evidence. The alignment wrote itself.

Time crunched? Run inquiry sprints. Twenty minutes daily for two weeks beats a single 90-minute block. My 8th graders tracked erosion patterns in twenty-minute daily observations. They retained more than the class that tried to do it all in one period. Momentum matters more than marathon sessions.

When Students Struggle With Open-Ended Tasks

I use the Goldilocks Intervention when groups stall. First, I check their resources—five to seven sources is the sweet spot. Less than that and they can't triangulate evidence; more and they drown in information. Second, I check if the question is actually investigable. "Why do we dream?" sparks curiosity but resists research in sixth grade. "How does sleep duration affect test performance?" gives them traction. Third, I check for prerequisite knowledge gaps that I assumed they had.

I assign investigation buddies to stop the procedural bottleneck. Before groups collect data, pairs check each other's methods. They catch missing steps or unclear variables before I get twenty hands raised. It builds accountability and frees me to work with the kids who really need me.

Hint cards save me during discovery learning. I print three levels of scaffolding on different colored paper. Students can trade participation points to buy a hint when stuck. Level one points to a resource. Level two models the thinking. Level three gives a partial answer. They stay in the driver's seat while I avoid the rescue trap.

Balancing Curriculum Standards With Student-Driven Inquiry

Standards panic kills good inquiry. I use standards-based portfolio reflections where students document which skills they practiced during each phase. They screenshot evidence from their research log and caption it: "This shows me analyzing primary sources, Standard RH.6-8.6." Suddenly the balancing curriculum standards with student-driven inquiry becomes visible to administrators and parents.

For tested subjects, I follow a 60/40 pacing guide. Sixty percent of our time goes to inquiry based learning strategies; forty percent covers direct instruction for tested content. I flip that ratio for electives. This keeps me sane during benchmark season without abandoning developing adaptive thinking skills in students.

I weight assessment rubrics fifty-fifty between process standards and content standards. Yes, they need to know the causes of the Civil War. But they also need to know how to evaluate conflicting sources. Both appear on the report. Parents stop asking "Where are the worksheets?" when they see the inquiry skills listed right next to the content grades.

One Thing to Try This Week

Pick one lesson you’re teaching next week. Swap your usual opener for an essential question that actually bugs you. Not a fact-check. Something like “Why do we still study ancient civilizations?” or “Is a hot dog a sandwich?” Watch what happens when you resist the urge to give the answer. I tried this with my 7th graders last spring. The silence hurt for about thirty seconds. Then they started arguing. Real arguing. That noise? That’s constructivist pedagogy happening without the buzzwords.

Your first step today? Write that question on a sticky note. Slap it on your monitor. When you plan tomorrow, build just one moment of scaffolded instruction—maybe a sentence starter or a data chart—that keeps kids digging. You don’t need to flip your whole classroom or master inquiry based learning strategies overnight. You just need to stop talking ten minutes sooner and let them stumble toward the discovery. That’s it. That’s the start.

Prerequisites — Establishing the Foundation for Inquiry Based Learning

Creating Psychological Safety for Intellectual Risk-Taking

You can't launch into inquiry based learning strategies on day one. I learned that the hard way with my 7th graders who shut down the moment I asked them to "wonder" about chemical reactions. They needed permission to be wrong first.

Block out three to five class periods upfront. Forty-five minutes each. That's the investment that makes inquiry based learning and constructivism actually work in a real classroom with real kids who've been trained to raise hands for correct answers.

I open with Columbia University's Community Agreements. I post four non-negotiables: All ideas get a five-minute testing period, no killer phrases like "that won't work," we build with "Yes, and..." not "but," and confusion is data not failure. We practice these with low-stakes improv games before touching content. One student suggests we study pizza instead of cells; another adds "Yes, and we could measure the yeast respiration." That's the protocol working.

The Circle of Viewpoints routine from Harvard Project Zero changes everything. Before we investigate anything, students physically move to different spots in the room to argue from the perspective of the mitochondria, the lab safety inspector, or the budget-conscious principal. It trains them to hold multiple hypotheses without committing to one immediately.

That's pure constructivist pedagogy in action—Piaget's cognitive conflict theory suggests we learn when our existing models clash with new evidence. If kids won't voice their initial models, that conflict never happens. We are literally manufacturing the disequilibrium Piaget described.

Failure logs are non-negotiable in my guided inquiry setup. Each student records three unsuccessful attempts before declaring success. Last October, Maria documented her three bridge designs that collapsed before the fourth held weight. When she presented, she led with the failures. The class nodded along because their failure logs looked similar. This models Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development—we scaffold intellectual risk by making struggle visible and shared.

Before opening the first investigation, run the Question Formulation Technique. Students generate questions following four rules: ask as many as possible, don't stop to judge, write exactly as spoken, and change statements into questions. We do this with random objects—a paperclip, a leaf—so the stakes stay low. By week two, they're ready to attack essential questions about erosion or civil rights using the same muscle.

Organizing Physical Space and Resources for Investigation

Your room layout signals how inquiry based instructional strategies actually work. I rearrange my classroom for 28 to 32 students into six investigation clusters, each with a home base table of five or six kids. They can see all four to six activity stations from their seats without craning necks. This matters because wandering wastes time and breaks focus.

Each investigation station functions as a dedicated resource hub with clear sightlines from the home bases. I stock five to seven toolkits at each of the four to six stations. Station one holds exactly five digital scales, measurement tapes, and calculation journals. Station two has primary source bins with 1900s immigration photos and magnifying glasses. Station three contains circuit boards and multimeters.

When tools have specific homes using the mise en place method, decision paralysis disappears. Kids grab and go instead of hunting through cluttered bins.

Budget $200 to $500 for reusable equipment upfront. Digital scales run $25 each. Plastic bins cost $5 at Target. Primary source prints are free from the Library of Congress. That's your inquiry based learning methods starter pack. You're set for three years of discovery learning.

Maintain a 60/40 split of digital to physical resources. I keep one device for every two students, but every station has offline backups stored in the resource hub. When the Wi-Fi crashes during a measurement lab, students reach for the analog rulers and graph paper taped underneath the tables. Equity means inquiry continues whether the internet cooperates or not. Check out effective classroom design and learning zones for layout diagrams that actually fit 30+ desks.

Front-load three to five class periods—forty-five minutes each—to establish these systems. Day one covers the Community Agreements. Day two practices the failure logs with a simple tower-building challenge. Day three introduces the Question Formulation Technique with that paperclip. By day four, when you finally unveil the essential question about kinetic energy, they're ready to investigate instead of asking "how do we start?" That's scaffolded instruction done right. The preparation feels invisible because you built it beforehand. When they finally sit for a Socratic seminar in week three, the protocols feel automatic.

Step 1 — Frame Compelling Questions That Drive Investigation

Essential questions transfer across years: "How do communities balance competing needs?" Supporting questions make investigation possible. For 7th-grade watersheds, pair that with "What percentage of our river’s pollution comes from agricultural runoff?" Match "Who decides how land gets used?" with "Which zoning laws changed in our county since 1990?" Pair "Why do ecosystems change?" with "How did wolf removal affect Yellowstone’s vegetation?"

I use the Question Formulation Technique for student-generated entry points. It’s a 30-minute protocol with four rules: ask as many as you can, do not judge or answer them, record every question exactly as asked, and change statements into questions. I give a Question Focus like "Our cafeteria wastes 200 pounds of food weekly," and set a 10-minute timer.

Before committing, students run the feasibility filter. Can we access data within two weeks? Does it require ethical approval? Is it testable? Then I provide grade-specific stems. K-2 asks "Why do..." Third through fifth uses "What happens when..." Sixth through eighth frames "How does X affect Y..." High school tackles "To what extent..."

Crafting Essential Questions That Spark Curiosity

Wiggins and McTighe’s six facets help me test my questions. Can students explain it? Interpret through art? Apply to their neighborhood? Consider perspectives? Show empathy? Demonstrate self-knowledge? If it hits fewer than three facets, it’s trivia. "Why did the Civil War start?" fails. "How do societies heal after being torn apart?" passes.

I convert closed questions using the How/Why shift. "What is photosynthesis?" becomes "How do organisms convert energy without consuming other living things?" The first gets a textbook paragraph. The second demands comparing autotrophs to heterotrophs. I ban "What is" and "List the." If Google answers it in one sentence, I reframe it into discovery learning.

Then I run the Monday Morning Test. Can students engage before any instruction? Last October, my 7th graders argued for fifteen minutes about "How does where you live affect what you believe?" using only experience. That friction—the not-knowing-yet—pulls them through the unit. No Monday Morning engagement means no inquiry.

This takes practice. My first year, I thought "What is democracy?" was essential. It wasn’t. Now I write questions on Friday and let them sit. If kids won’t argue in the hallway, I rewrite. The best questions feel uncomfortable. That discomfort is the engine of guided inquiry.

Teaching Students to Generate Their Own Investigable Questions

I teach students to climb the Question Ladder before selecting investigations. Level 1 asks facts: "When was the Emancipation Proclamation signed?" Level 2 analyzes: "Why did Lincoln choose that timing?" Level 3 synthesizes: "How might the Civil War have ended differently without that document?" Students generate two at each level before picking one Level 3. This prevents Google-able trivia or impossible research.

Sentence frames help reluctant starters. I post: "I wonder if ____ affects ____ because ____" and "What would happen if we changed ____?" These force students to identify variables. A kid writes, "I wonder if sunlight affects mold growth because I’ve seen bread get fuzzy near windows." That’s investigable. The frames scaffold the move from curiosity to hypothesis without me doing the thinking. This is scaffolded instruction.

We use the 20-10 timeline. Twenty minutes of generation, then ten minutes of peer review using the Thickness Test. Can we find multiple valid answers? One textbook answer means too thin. Three interpretations backed by evidence means thick enough. This protocol is one of my core inquiry based learning strategies for teaching students to generate their own investigable questions.

Last spring, my 8th graders studied local water quality. One group started with "What is pH?"—a Level 1 dead end. Using the ladder and "I wonder if" frame, they landed on "How does agricultural runoff affect stream pH near farms versus forests?" That’s testable. Find more inquiry-based teaching examples here. Don’t hand them the question. They must build it.

Step 2 — Design Scaffolded Discovery Activities

Selecting the Right Level of Inquiry (Structured to Open)

Herron's taxonomy breaks inquiry into four levels running from teacher-heavy to student-driven. Level 0 is confirmation—students verify a known result, like proving vinegar and baking soda make gas. Level 1 is structured inquiry where you pose the question and provide the procedure. Think of an 8th-grade density lab where you give steps but they measure mass and volume.

Level 2 shifts to guided inquiry—you set the problem, but students design the method. Those same 8th graders might test whether fresh or saltwater freezes faster. Level 3 is open inquiry where students pose the question and design the method. Save that for juniors and seniors doing capstones, not middle schoolers.

Picking the wrong level kills momentum. If they finish in ten minutes flat, you over-scaffolded. If they stare at materials for fifteen minutes without touching anything, you went too open. Run a quick safety check first. Have they mastered goggles-and-gloves protocols? If no, stick to Level 1 even if you want to let go. Is the concept foundational? Then apply the 40-40-20 formula: forty percent researching and designing, forty investigating, twenty analyzing. For structured inquiry, flip that to 20-60-20 since the design is mostly done. Selecting the right level of inquiry means matching the autonomy to their readiness, not your idealism.

Curating Resources Without Removing the Intellectual Challenge

Throwing twenty links at kids creates paralysis. Giving them one source kills critical thinking. The Goldilocks Rule sweet spot is five to seven vetted sources. Include one deliberate distractor—maybe a blog post with clear bias about climate change—to force them to evaluate reliability. Build your banks in Padlet or Wakelet and tag them green, yellow, or red for difficulty.

Green hits grade level for struggling readers. Yellow pushes the 1.5 Rule: texts written about a year and a half above grade level work when kids read in pairs. Red sources are college-level abstracts for your advanced kids who need real teeth to bite into.

Set up your investigation banks before the unit starts. Drop in videos, infographics, and primary sources that answer different parts of the driving question. When students hit a roadblock, they learn to navigate the bank before calling you over. This builds the self-sufficiency that constructivist pedagogy demands. It also keeps you from becoming the human search engine.

Timing matters. Handing over procedure sheets at minute zero trains them to follow recipes. Instead, use just-in-time release. Let them wrestle with the design problem for fifteen minutes first. When they hit walls, push out the procedural hints. This keeps the intellectual work on their shoulders while preventing total shutdown. Scarcity breeds dependence; overload breeds copy-paste. Seven sources, one trap, and a fifteen-minute struggle window—that is how you scaffold without stealing the discovery. Inquiry based learning strategies fail when we remove the struggle entirely.

Step 3 — How Do You Facilitate Evidence Collection Without Taking Over?

Facilitate evidence collection by using structured protocols like Conver-Stations or the Harkness Method, where the teacher physically removes themselves from the discussion center. Implement Rowe's Wait Time (3-5 seconds of silence after questions) to force student-to-student dialogue, and enforce the 'Three Before Me' rule requiring students to consult peers and texts before asking you for procedural help.

Your job is to become invisible. Not absent—just peripheral. When you occupy the center, kids look to you for answers. These protocols shift that gravitational pull toward the texts and toward each other.

I learned this the hard way during a Civil War inquiry unit. I kept jumping in to "clarify" at Station 3, and by the end, every group had identical conclusions—mine. Now I run Conver-Stations with four distinct document sets spread around the room. Kids rotate every twelve minutes with a specific collection sheet. I stand near the file cabinets, coffee in hand, literally forcing myself to stay outside the circle.

Rowe's Wait Time feels like torture at first. You ask a question, then count to five in your head while the silence screams. But that pause lets kids process instead of panic. Pair it with the Harkness Method—the oval table setup from Phillips Exeter where you sit outside the rim. I sketch a name map to track who speaks, and I don't break in until the silence hits two full minutes. They always break first.

The Three Before Me rule keeps me from becoming Google. Students must check their textbook, ask a table partner, and search our digital database before they raise a hand for procedural help. Last Tuesday, Marcus started to ask me where to find the primary source about child labor. I pointed at the rule poster. He sighed, turned to Sarah, and found it in ninety seconds. That's the point.

Data Gathering Techniques for Different Grade Levels

Scaffolded instruction means matching the tool to the developmental stage, not dumbing down the thinking. For kindergarten through second grade, I use picture sorting protocols. Each station gets fifteen to twenty laminated images—factories, rivers, faces from history—and tally sheets with icons instead of words. They sort by "Then/Now" or "Happy/Sad" and mark their counts with stickers. The icons let pre-readers work independently while the teacher circulates to listen for reasoning.

Third through fifth graders handle structured observation journals. I print the four-column layout: Observe, Wonder, Connect, Evidence. They sketch what they see in the artifact photo, write one question, link it to a prior reading, and cite the source number. It keeps their hands busy and their brains anchored. I collect these midway through the period to check for off-track assumptions without lecturing.

Middle schoolers need guided inquiry with real teeth. I send them on database scavenger hunts using JSTOR School Edition. They must bring back three cited quotations with page numbers, not just facts. When they realize they can't copy-paste from academic abstracts, they start reading closely. That's when the discovery learning actually starts.

Teaching Critical Source Evaluation Skills

Kids will cite anything that pops up first on Google if you let them. I teach the CRAAP test—Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose—to sixth through twelfth graders using a laminated checklist rubric they keep in their binders. They physically check off each letter before a source enters their notes. It slows them down for exactly three minutes, then saves them from citing Wikipedia in their final essays.

For younger students, I simplify with the Trustworthy Triangle. We ask three questions: Does the author know the topic? Does she tell the truth? Does she want to help us learn? If any corner wobbles, we find a better source. I model this with a ridiculous website about flying sharks to make the red flags obvious.

Speaking of flags, every student gets a critical source evaluation skills card listing the warning signs: missing publication dates, words like "uproarious" or "shocking," and websites ending in .com with no citations. Once they spot these in practice, they start policing each other. That's when I know the inquiry based learning strategies are sticking—they're protecting their own research integrity.

Step 4 — Guide Students to Synthesize Evidence and Draw Conclusions

At this point in your inquiry based research project, kids have gathered evidence. Now they need to make sense of it. I use the Claim-Evidence-Reasoning framework: one claim, three data points, and two sentences explaining the science behind the evidence. It keeps them from listing facts.

Then we climb the So What? ladder: personal relevance, then community impact, then global significance. Last year, my 7th graders traced microplastics from our cafeteria to Arctic seabirds. That third rung hit hard.

For visual synthesis, they map connections using CmapTools or string and cards. They link evidence to claims with yarn. When the web gets messy, they see where reasoning breaks. These inquiry based learning strategies move kids from collecting to connecting.

Using Socratic Questioning to Challenge Assumptions

I keep a tracking sheet listing six categories: Clarification ("What do you mean by..."), Assumption ("What are you assuming..."), Evidence ("What supports..."), Viewpoint ("Is there another way..."), Consequence ("What are the implications..."), and Meta-questions ("Why does this matter?"). I check off each type to ensure variety.

When students run the Socratic seminar, I use a fishbowl. The inner circle discusses while the outer tracks fallacies. I heard a 10th grader pause last week and say, "Wait, I think I'm assuming correlation equals causation." using Socratic questioning to challenge assumptions works best when you release control gradually.

During guided inquiry, I model stems as scaffolded instruction, then hand them the script. By week three, they probe sources without prompts. The constructivist pedagogy sticks when students internalize the habit, not just answer your essential questions.

Connecting Findings to Prior Knowledge and Real-World Applications

Skip the standard KWL chart. I use KWL+—the plus stands for Action. Students effectively use evidence to back up arguments when they know a real audience waits. I have used these in diverse inquiry based lessons, sending kids to city council for inquiry based project examples, science journals, or museum exhibits.

The CER framework shines here. Students write one claim, cite three evidence pieces, then connect to principles in two sentences. I test their conclusion with a transfer task: "If you saw this pattern in economics, what would you predict?" It exposes gaps fast.

Discovery learning falls flat without these bridges. Last semester, students studying water quality realized their data mirrored 19th-century cholera maps. They strung yarn between evidence cards and John Snow's findings. That's synthesis you can see.

Common Pitfalls and How to Troubleshoot Implementation Challenges

When students go off-task five minutes into an investigation, the problem usually isn't motivation—it's the task design. I run a quick diagnostic: too much freedom often means the cognitive load exceeded their working memory. The fix takes five minutes. I add a constraint, like requiring evidence from at least three sources before they move to analysis. That single parameter refocuses the room without killing the inquiry.

I also use a Productive Failure protocol when I see blank stares. I let them struggle with the essential question for twenty minutes. No hints. Then I pause for ten minutes of just-in-time direct instruction targeting the specific gap I observed. We return to the inquiry immediately. This cycle respects constructivist pedagogy while preventing shutdown.

Start with backward design (Wiggins & McTighe) to avoid standards misalignment. I pick two priority standards first, then build the inquiry to require those skills. Last year I targeted RI.7.8 and W.7.1b for an argument unit. Every investigation step required tracing claims and using evidence. The alignment wrote itself.

Time crunched? Run inquiry sprints. Twenty minutes daily for two weeks beats a single 90-minute block. My 8th graders tracked erosion patterns in twenty-minute daily observations. They retained more than the class that tried to do it all in one period. Momentum matters more than marathon sessions.

When Students Struggle With Open-Ended Tasks

I use the Goldilocks Intervention when groups stall. First, I check their resources—five to seven sources is the sweet spot. Less than that and they can't triangulate evidence; more and they drown in information. Second, I check if the question is actually investigable. "Why do we dream?" sparks curiosity but resists research in sixth grade. "How does sleep duration affect test performance?" gives them traction. Third, I check for prerequisite knowledge gaps that I assumed they had.

I assign investigation buddies to stop the procedural bottleneck. Before groups collect data, pairs check each other's methods. They catch missing steps or unclear variables before I get twenty hands raised. It builds accountability and frees me to work with the kids who really need me.

Hint cards save me during discovery learning. I print three levels of scaffolding on different colored paper. Students can trade participation points to buy a hint when stuck. Level one points to a resource. Level two models the thinking. Level three gives a partial answer. They stay in the driver's seat while I avoid the rescue trap.

Balancing Curriculum Standards With Student-Driven Inquiry

Standards panic kills good inquiry. I use standards-based portfolio reflections where students document which skills they practiced during each phase. They screenshot evidence from their research log and caption it: "This shows me analyzing primary sources, Standard RH.6-8.6." Suddenly the balancing curriculum standards with student-driven inquiry becomes visible to administrators and parents.

For tested subjects, I follow a 60/40 pacing guide. Sixty percent of our time goes to inquiry based learning strategies; forty percent covers direct instruction for tested content. I flip that ratio for electives. This keeps me sane during benchmark season without abandoning developing adaptive thinking skills in students.

I weight assessment rubrics fifty-fifty between process standards and content standards. Yes, they need to know the causes of the Civil War. But they also need to know how to evaluate conflicting sources. Both appear on the report. Parents stop asking "Where are the worksheets?" when they see the inquiry skills listed right next to the content grades.

One Thing to Try This Week

Pick one lesson you’re teaching next week. Swap your usual opener for an essential question that actually bugs you. Not a fact-check. Something like “Why do we still study ancient civilizations?” or “Is a hot dog a sandwich?” Watch what happens when you resist the urge to give the answer. I tried this with my 7th graders last spring. The silence hurt for about thirty seconds. Then they started arguing. Real arguing. That noise? That’s constructivist pedagogy happening without the buzzwords.

Your first step today? Write that question on a sticky note. Slap it on your monitor. When you plan tomorrow, build just one moment of scaffolded instruction—maybe a sentence starter or a data chart—that keeps kids digging. You don’t need to flip your whole classroom or master inquiry based learning strategies overnight. You just need to stop talking ten minutes sooner and let them stumble toward the discovery. That’s it. That’s the start.

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

Table of Contents

Modern Teaching Handbook

Master modern education with the all-in-one resource for educators. Get your free copy now!

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.

2025 Notion4Teachers. All Rights Reserved.